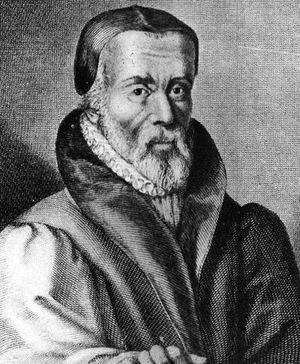

William Tyndale — the man who gave England her Bible (2)

Phil Arthur

William Tyndale – the man who gave England her Bible April 2011 (1)

William Tyndale — the man who gave England her Bible (2)

William Tyndale — the man who gave England her Bible (3)

William Tyndale — the man who gave England her Bible (4)

William Tyndale — the man who gave England her Bible (5)

William Tyndale — the man who gave England her Bible [6]

William Tyndale knew that he was not the first Englishman to attempt the task of translating the Scriptures out of the original languages into English.

In his The obedience of a Christian man Tyndale observed that he had read as a child how King Athelstan had ’caused the Holy Scripture to be translated into the tongue that then was in England’ and that the bishops of that era had encouraged him to do so (B. Moynihan, If God spare my life, London, 2002, pp. 155-156).

Tyndale’s reason for mentioning this was his sense of outrage that senior clergy prior to the Norman Conquest should do their duty so assiduously, while, by contrast, the senior clergy of his own day did everything in Latin except curse.

He was poignantly aware that there had been a time in the life of his nation when leading churchmen believed that the Bible would do most good when people understood it best, whereas now, in the early 16th century, the opposite conviction seemed to have gained ground, namely that it would do most good when people were mostly ignorant of its contents.

Older versions

By the 11th century, substantial portions of the Bible had been translated into Anglo-Saxon (or old English — spoken in England from the 6th-12th centuries; J. R. R. Tolkien, author of Lord of the Rings, put it in the mouths of the Riders of Rohan), including the remarkable running translation, between the lines of the Vulgate of the Lindisfarne Gospels, by a 10th century scribe named Aldred.

We could also mention those early chapters of John’s Gospel translated by Bede of Wearmouth and Jarrow, sadly lost to us; translations of the Psalms by Alfred of Wessex; and Old Testament material translated by Ælfric of Eynsham.

Even then, few English people were literate and few copies of these treasures existed outside monastic writings. Equally, Tyndale’s reference to ‘the tongue that then was in England’ shows his awareness of the fact that Anglo-Saxon was no longer the spoken language of English people.

The political and social convulsions of the Norman conquest had set many cataclysmic changes in motion, not least among which was the fact that the English language, which became the tongue of a dispossessed and conquered people whose governing élite spoke Norman French for the next three centuries, went through a series of drastic changes between King Athelstan’s day and that of Tyndale’s sovereign, Henry VIII.

A modern teenager who reads Geoffrey Chaucer or William Langland’s Piers the ploughman with its Lollard overtones, or for that matter the Wyclif Bible, is reading Middle English (transitional form spoken from the 12th-14th centuries, prior to the emergence of modern English in the late 15th century).

Anglo-Saxon

He may need the help of a good glossary, but he is reading something that is recognisably English for all that. Anglo-Saxon is so far removed from modern English that a modern student who wishes to read Beowulf or the devotional poetry of Cædmon must either learn the language or purchase a

translation. Englishmen alive in Tyndale’s lifetime may have lived four centuries closer to King Athelstan than we do, but the Anglo-Saxon vernacular was no more accessible to them than it is to us as this extract will show:

‘Ælc þara þe þas min word gehierþ, and þa wyrcþ, biþ gelic þæm wisan were, se his hus ofer stan ge-timbrode. Þa com þær regen and micel flod, and þær bleowan windas, and a-hruron on þæt hus, and hit na ne feoll: soþlice hit wæs ofer stan ge-timbrod’ (Matthew 7:24ff; cited in Sweet’s Anglo Saxon primer, OUP, Ed. Norman Davis, 1974, p.62).

It could be argued that it was a different matter when it came to the existence of Lollard Bibles. In some parts of the country at least, these were fairly widespread. These were manuscript translations made before the invention of printing during the 14th century.

They were third-hand translations, taken not from the original languages but from the Latin Vulgate, rendered into the English of the day, namely Middle English. The impetus for his project came from John Wyclif of Oxford.

Lollard Bibles

An enormous quantity of material — portions of some 250 Wycliffite Bibles — is still extant. It used to be thought that there was an earlier edition, largely the work of Wyclif himself, and a later edition produced by one John Purvey. But the painstaking work of two Victorian scholars, Forshall and Madden, in surveying the great bulk of surviving texts, while agreeing that there appear to be more or less two versions in existence, an earlier and a later, has failed to establish the identity of any particular translator, apart from one Nicholas of Hereford.

It seems that Tyndale had not actually seen a Lollard Bible himself. When the Worms New Testament came out, he claimed that he had not consulted any English sources ‘that had interpreted the same or such like thing in the scripture beforetime’ (Moynihan, p.56).

This is not to minimise the good that had been done over several generations while Lollard Bibles circulated in clandestine fashion at a time when the ownership of such items was a capital offence.

Nonetheless, we should recognise that even if the Constitutions of Oxford had been scrapped and the new technology of printing had allowed Wycliffite Bibles to circulate freely and cheaply, these were not the answer to the spiritual needs of Englishspeaking people.

Firstly, this was because even the vastly superior Later Version was much too close to the Latin of the Vulgate. Compare these two extracts from Colossians 2:13-15. The first is the Wycliffite Later Version; the second from Tyndale’s Worms New Testament of 1526.

‘And whanne ye weren deed in giltis, and in the prepucie of your fleisch, he quikenyde togidere you with hym foryiving to you alle giltis, doynge awey that writing of decre that was ayens us, that was contrary to us; and he took away that from the midyll, pitching it on the cross; and he spuylide principatis and poweris, and he led out tristlii, opynli, ouercominge hem in hym silf’ (Eds. Josiah Forshall & Frederick Madden, IV, p.433).

‘And hath with hym quyckenened you also which were deed in synne and in the uncircumcision of your flesshe, and hath forgiven us oure trespasses, and hath put out the obligacion that was against us, made in the law written, and that hath he taken out of the waye, an hath fastened it on his crosse, and hath spoyled rule and power, and hath made a shewe of them openly, and hah triumphed over them in his awne person’ (The New Testament translated by William Tyndale (1526); ed. W. R. Cooper, 2000, p.427).

Delight

Aside from the sheer woodenness of translating from the Latin rather than the Greek, the English of the Lollard Scriptures was now 150 years out of date. There is good reason to believe that courageous believers who had loved their Lollard Bibles for want of anything else turned with relief to the new Tyndale Testaments when they could get them, delighting in the freshness and intelligibility they found there. Two men from Steeple Bumpstead in Essex for instance made the journey to London so that they could trade in their Lollard Bibles for Tyndale New Testaments.

A different line of argument has been offered altogether by historians who might best be described as Catholic revisionists. Their case is essentially that Tyndale need not have bothered, that left to itself the Church was well on the way to providing the English people with large quantities of Scripture in the form of devotional manuals and books of hours, and that without the trauma of the Reformation more would have followed in due course.

One of the leading proponents of this view is Eamon Duffy in his book The stripping of the altars. One example of the kind of literature in question was the rather fanciful Mirror of the life of Christ produced by Nicholas Love, prior of the Carthusian monastery of Mount Grace de Ingleby in Yorkshire.

Sentimentality

Consider this extract about the circumcision of Jesus, which merits only a few words in Luke’s Gospel: ‘Dear Son, if thou wilt that I cease of weeping, cease also thy weeping: for I may not but weep, what time that I see thee weep. And so through the compassion of the mother the child ceased of sobbing and weeping, and then his mother, wiping his face and kissing him and putting the pap in his mouth comforted him in all the manners that she might’ (Cited in D. Daniell, William Tyndale — a biography; Yale, 1994, p.97).

It is little wonder that no one was ever burned alive for purchasing such anodyne collections of maudlin sentimentality, while in the meantime English people were sufficiently desperate to learn what God was saying in his Word as to put their lives at risk to own a copy of that Word.

To be continued