Everything changed for the church in AD 313, when the Edict of Milan allowed complete freedom for Christian worship. The previous year the Emperor Constantine had decided to make Christianity the official religion of the Empire.

Some would say that Constantine was converted. However, it is unlikely that he was truly born again. He merely saw political advantage in making Christianity the ‘established’ faith. The changed situation soon became evident. In 315 Christian symbols began to appear on Roman coins, and by 323 the remaining pagan symbols finally disappeared.

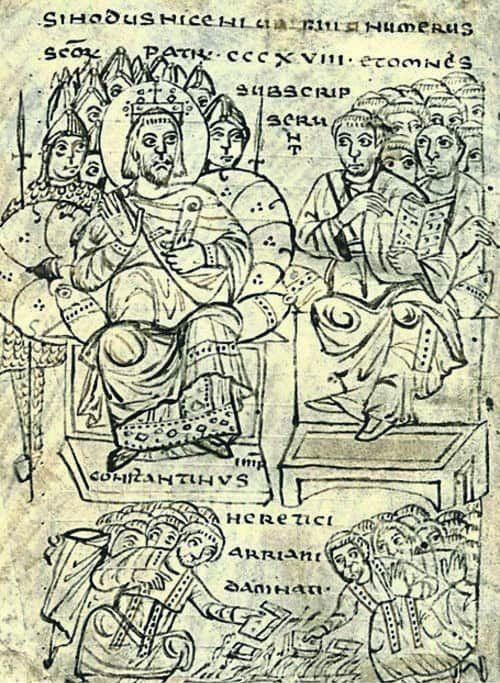

Council of Nicaea

In some ways this change in status was a blessing for the church. The end of persecution led to great growth, though it also meant an increase in nominalism. However, the down-side was seen especially in the way that emperors began to view themselves as heads of the church as well as the state. There was a real danger that the church would come under political control. Despite that, we see wonderful evidence of God’s overruling providence in the way that doctrinal disputes were settled. Biblical truth was preserved, when it could so easily have been lost.

Take the Council of Nicaea, for instance. This was convened by Constantine because there was disagreement in the church over the person of Christ. Some people maintained that Christ was fully divine. Others, called Arians, taught that he only resembled God: he was a creature, the highest creature to be sure, but still only a creature.

The proceedings began in June 325. About 300 representatives were present from congregations throughout the Empire. Constantine presided. He barely understood the issue, and hardly cared which doctrine prevailed. His main concern was that everyone should agree, whatever was decided.

Well, praise God, the truth prevailed. By the time the representatives were travelling home two months later, a creed had been agreed teaching that Jesus Christ is the eternal Son of the Father, that he was active in the creation of the world, and that he became a human being in order to save us. God had overruled and preserved the church from error.

Truth upheld

This does not mean that the Arians gave up. When Constantine died in 337, the Empire was divided between his two sons. However, while one of them favoured the true faith upheld at Nicaea, the other sided with the Arians. This led to a further period of wrangling and controversy, which was not brought to an end until Constantine’s sons had been dead for twenty years.

It was May 381 when the reigning emperor, Theodosius, summoned a Council at Constantinople. The 150 representatives who attended reaffirmed the teaching agreed at Nicaea, and Arianism soon all but died out.

The dispute over the person of Christ was to erupt again 60 years later. It raged for 10 years, until another Council met at Chalcedon during October 451. This time 520 representatives were present. Again the truth put into words at Nicaea was upheld.

This Council gave the church a statement of the doctrine of the person of Christ which still remains the standard definition. It taught that Jesus Christ was only one person, yet he had two natures, divine and human, both perfect and complete, and not somehow mixed to become a third essence. It taught that Christ’s human nature was sinless, that he was eternal as God, but that he had a beginning in time as a human, coming into the world to save us.

Essential basis

We recognise this as the essential basis of the gospel. Jesus only has power to save if he really is God, and he is only able to save us if he is completely human, but sinless. The definition agreed at Chalcedon began, ‘We all with one voice confess our Lord Jesus Christ’. And ever since, the true church everywhere has rejoiced to confess him true God, really human, our wonderful Saviour. Again we see the marvellous providence of God: in circumstances of political control the truth was protected and maintained.

The history of the church in Western Europe for the next 150 years was dominated by two men, both Bishops of Rome, Leo (bishop from 440-461), and Gregory (590-604).

Leo actually played an important part at Chalcedon, although he was not there. Circumstances prevented him from attending. So on 26 June 451 he sent to the Council a work of his, known as The Tome, in which he laid down ‘the loyal and pure confession’ of the doctrine of the person of Christ. The final statement at Chalcedon drew heavily on Leo’s Tome.

Splendid statement

A few sentences will give a flavour of Leo’s understanding of the two natures of Christ. He writes: ‘Without detriment to the properties of either nature – which then came together in one person, majesty took on humility, strength weakness, eternity mortality. Being invisible in his own nature, he became visible in ours, and he whom nothing could contain was content to be contained.

‘Abiding before all time, he began to be in time. For he who is true God is also true man, and each nature does what is proper to it with the co-operation of the other. One of them sparkles with miracles, the other succumbs to injuries. The nativity of the flesh was the manifestation of human nature, the child-bearing of a virgin is the proof of divine power.

‘The infancy of a babe is shown in the humbleness of his cradle, the greatness of the Most High is proclaimed by the angels’ voices. To be hungry and thirsty, to be weary and to sleep is clearly human: but to satisfy 5000 men with five loaves, and to walk on the surface of the sea with feet that do not sink, and to quell the risings of the waves by rebuking the winds is, without any doubt, divine’.

Such a splendid statement makes the heart rejoice. We should be very thankful that God raised up in those early centuries men able to stand for the truth when it was under attack.

Harmful tendencies

But we need to remember the words of James 3:2: ‘We all stumble in many things’. This reminds us that the best of Christian teachers get some things wrong. As 1 Corinthians 13:12 says, ‘Now we see in a mirror dimly … Now I know in part’.

Leo, for all the good he did in standing up for biblical truth about Jesus, also set in motion tendencies which would prove bad for the church.

Leo believed that when Jesus said to Peter, ‘you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church’ (Matthew 16:18), he meant that Peter was the rock, the chief apostle, the leader of the whole church.

He also believed that Peter spent some time in Rome (which was true), and was the first pastor of the church there (which he was not). But these beliefs led Leo to teach that all Peter’s successors as pastors at Rome had inherited his leadership role over the whole church.

In fact, Leo taught that Peter’s own apostolic ministry continues through the current leader of the church at Rome; that is, Peter himself is the permanent leader of the whole worldwide church, because he continues to speak through the men who succeed him.

It is obvious where this was leading. Until Leo’s day, Rome was just one of a number of influential Christian centres. When Leo died in 461 the foundations had been laid for the development of Roman Catholicism and the papacy.

The power of Rome

Over 100 years were to pass before Gregory became Bishop of Rome in 590, but he really completed the work which Leo had begun. By his time, the western half of the Roman Empire was on the verge of collapse. The Lombards were invading. The results were famine and plague.

Soon the Lombards were threatening to overrun Rome itself. The situation was desperate, yet the imperial rulers were powerless. A power-vacuum developed, and into it stepped Gregory.

He took command in a big way. He managed to secure provisions for Rome. He started sending orders to the generals fighting against the Lombards. He negotiated directly with the Lombard leaders, and finally concluded a peace treaty with them. And all this without any authorisation from the political ruler! In effect, the Bishop of Rome had become the political ruler of Italy.

But Gregory wanted more. He wanted the entire church, indeed the entire world, to be united as a Christian commonwealth under the leadership of the Bishop of Rome. He therefore set about spreading the real power of Rome throughout the western Empire.

A classic example is the way he sent a monk to England in AD 597. Officially, this was to convert England to Christianity. Perhaps, more truthfully, it was to bring the English Church (known as Celtic Christianity) under the authority of Catholic Rome.

Gregory has been described as ‘the first medieval Pope’. Certainly, when he died in 604 the western world was on the doorstep of the Middle Ages.