Two-year-old Tom Barnardo lay critically ill. Frail from birth, the child had battled constantly against ill health. But now, as his anxious parents watched over their sick boy, it seemed that this time they must lose him. With heavy hearts they recognised that the child’s life was slipping away. And at last the doctor in attendance pronounced him dead. A second doctor confirmed the sad news and no option remained for the grieving parents but to call in an undertaker.

With the little coffin made and already waiting in the house, the undertaker was preparing the child’s body for burial. Suddenly he became conscious of a tiny flutter of movement: then another, and another. Tom Barnardo was not dead. Gradually, very gradually, Tom was nursed back to health and was to become a sturdy and resilient youngster. Snatched back from the very gates of death, this child was destined in God’s purposes to rescue many another young life from conditions which could only be called a living death.

A great deal of trouble

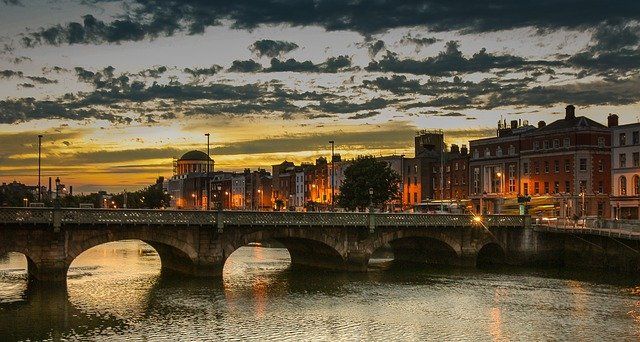

‘A bit of all sorts’ was the way Tom Barnardo was to describe his nationality in terms of the blood that ran in his veins. Born in Dublin in 1845, Tom had an English mother. His father John Barnardo, however, claimed Turkish, German, Spanish and Italian ancestry. Such a mix produced a quixotic, lively and unpredictable child. Young Tom, the ninth in the family, proved far from easy in the home. Described as ‘hot-tempered, self-willed and highly imperious’, he had wiry hair, plain features and a voice remarkable only for its volume. Far different was Harry, Tom’s younger brother, who with his fair hair, attractive features and beautiful singing voice, charmed all who came to the home. Often called from his play to sing to the guests, Harry soon aroused Tom’s animosity, particularly as his performances were usually rewarded with chocolates. On one occasion, as Harry returned from the sitting room where he had just sung to an admiring circle of visitors, he was also finishing off the last of the chocolates. Tom’s fury became uncontrollable. Delivering a well-aimed blow at his younger brother’s face, he yelled, ‘Take that for showing off in the drawing room’. And as Harry reeled from the impact, Tom delivered another blow with the words, ‘And that, you pig, for eating all the chocolates yourself’.

Recalling those days, an older brother wrote: ‘He was full of fun, mischief, thoughtless and careless. Do not suppose he was born a saint and always a saint. He gave a good deal of trouble at home…At his first school he gave no end of trouble and at [his second] school was no better’. But by the age of fourteen Tom Barnardo began to reveal a more serious side to his nature. Reading became his predominant delight, though his school-books ran a poor second in his selection of reading material.

A transforming message

Philosophical and atheistic writers became young Tom Barnardo’s first choice, as the ideas of Voltaire and Tom Paine moulded his thinking. By the time he was fifteen he declared himself an agnostic, repudiating any religious impressions he had imbibed from his Quaker mother or from the Church of Ireland, into which he had been baptised as an infant. His confirmation that same year was therefore a mere formality – an exercise in hypocrisy. Organised Christianity, and even the Bible itself, simply provided material for young Barnardo’s cynical jokes. Leaving school at the age of sixteen with few academic attainments, Barnardo took up a business opportunity which his father procured for him. Here his innate abilities began to appear, though an increasing love of reading made the discipline of business life irksome to the young man.

The early 1860s were momentous years for the gospel of Christ in Ireland. Repercussions from a powerful revival of religion, which had begun in New York in 1858, had reached across the Atlantic and affected Northern Ireland profoundly during 1859. And now the crowded streets and homes of Dublin were being touched by the transforming message of the grace of God in Christ. Vast numbers gathered in the Metropolitan Hall, formerly a circus arena, to listen to the preaching of men like Henry Grattan Guinness.

Too close for comfort

Tom Barnardo had little time for such things. In fact, armed with the arguments of his favourite authors, he had an answer for all the amazing events taking place around him. ‘Emotional hysteria’, he called it, ‘a mere psychological phenomenon’. Converts of the revival, some of them his former friends, would soon revert to their former habits, predicted the arrogant seventeen-year-old. But beneath the surface, young Barnardo was more troubled than he liked to admit. And then the conquering power of the gospel of Christ came too close for comfort. Two of Tom Barnardo’s older brothers were converted.

Concerned for their younger brother, these two new converts urged Tom to accompany them to the meetings. But to no avail. Still they pleaded until at last he agreed to attend a smaller gathering in a private home, though his purpose was largely to disrupt the meeting with cheeky interjections. This he did and, describing the occasion many years later in a letter to the speaker at that meeting, he was to write, ‘I behaved very badly. I was just as cheeky as a young fellow can be’. But instead of dealing with him as he knew he deserved, the leader had spoken kindly to the impudent young man. This disturbed Barnardo far more than angry words could have done. ‘What if his brothers were right and he wrong?’ he pondered.

A new dawn

Despite his bravado this seed of doubt began to grow in Barnardo’s mind, and for the first time he started to question the ideas he had gained from his rationalistic reading material. No longer did he mock the religious convictions of his brothers and friends, but instead could be found regularly attending the meetings himself. Not many weeks later one message pierced through Barnardo’s soul like a knife. Now he knew for certain that not only was he wrong, but he had deeply offended against his God.

No sleep could he find that night. And in the small hours of the morning a weary and burdened young man crept into the room where his older brothers were sleeping. Many were the tears shed as his brothers tried to help him, for he was in much distress of soul. But before dawn broke, as the three knelt in prayer together, the tears were replaced by light, joy and peace from God. Tom Barnardo now knew himself forgiven for his sins and reconciled to God, through believing on the Saviour who had been crucified to pay the punishment his sins deserved.

Tireless zeal

The change was immediate and obvious. Now the dust began to gather on Barnardo’s former favourite authors. Instead the Bible, previously the subject of many a joke, became his constant delight as he studied its pages. Nor could he keep to himself the joy of his new-found peace with God.

With tireless zeal he flung himself into Christian service, enrolling as a teacher in one of Dublin’s ragged schools. Here, for the first time, he came face to face with the appalling poverty and degradation in which many children existed. ‘Had I a dog,’ he declared, ‘I would not kennel it where I found these immortal souls’. But not in a moment did Tom Barnardo cast off all the characteristics of his quick-tempered nature. Formerly he used to carry a cane wherever he went, but now he no longer dared to do so, in case the objectionable behaviour of some of his pupils provoked him to thrash out with his stick.

For some years after his conversion, Tom Barnardo continued his secular employment, but his heart was elsewhere. At last, in 1866, he was introduced to Hudson Taylor, the pioneer missionary to China. Enthralled by Taylor’s description of the limitless opportunities for the gospel in that far-off land, Barnardo volunteered for missionary service. At Hudson Taylor’s suggestion, the young man went to London to begin training.

Mission on his doorstep

Here in London, while studying medicine with a view to increased usefulness in China, Barnardo came face to face with such extremes of destitution and poverty among the cast-out and unwanted children of London’s East End, that his whole being was stirred to the depths. Renting a dilapidated cottage, then used as a donkey shed, Barnardo opened his own ‘ragged school’ for these waifs of London’s streets. There he met Jim Jarvis, a semi-clad and homeless urchin who declared, ‘Oi don’t live nowhere,’ and then showed the horror-stricken young man the roofs and dens where scores of other little boys were sleeping rough. That story, however, belongs to a longer treatment of Barnardo’s life.

Now he knew that his mission field was not the far-off shores of China but right there on his own doorstep. And from that small beginning sprang a work which was to reach not only the slums of London, but was to rescue children worldwide, bringing shelter, education, and work. More than all, it brought to those he helped the opportunity to hear of the saving grace of Christ, which had transformed a self-centred young man into a benefactor whose name is still a household word today.