At the heart of the Christmas message is a scandal. Let’s be clear about this. We are being told that God made himself known as our Saviour in one particular person, in one particular place, and at one particular time.

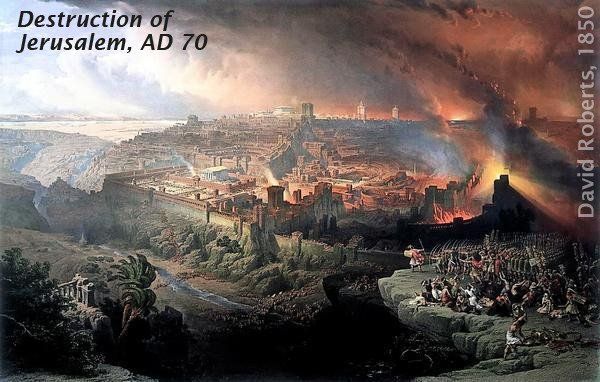

He decided to reveal himself through a group of insignificant people, living in a small Middle Eastern country 2000 years ago. The fragrant life of Jesus Christ flowered in a wasteland. The Son of the Most High was born in a slum.

The message is unambiguous – ultimate truth has been disclosed in one person alone. The secret of life is made known to us in the history and person of Jesus Christ.

Someone has called this ‘the scandal of particularity’.

History

The issue confronting us is one of historical fact. The Christian faith was first proclaimed by people who spoke of real historical events.

They carefully dated the onset of Mary’s pregnancy; they located his birth firmly in the context of their contemporary world; they described the special circumstances that brought Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem.

In sum, the four Gospels are set in a precise historical context. They describe in detail a remarkable life – which ended with a remarkable death and continued after a remarkable resurrection.

If history is what we read, write, and think about the past, then the Christian faith is just about as historical as you can get. We are invited to ‘come and see’ something grounded in human history.

Something extraordinary

Of course, there are people today who cast doubt on the relevance of history. Henry Ford called it ‘bunk’. They say that we cannot be sure about anything that happened in the past (nor even about what ‘history’ means).

This seems strange to most people, whose only problem with history at school was remembering it!

Others make too much of history. They claim to have special insight that allows them to interpret events and discover God’s hand in it all. They even claim the foresight to predict what will happen in the future.

To the rest of us, this sounds more like presumption than vision.

Nevertheless, the first Christians clearly emphasised history. They were sure that certain events had occurred in their world, events that made a vast difference to them. They realised that something quite extraordinary had happened – both to Christ and to themselves.

They had encountered a real historical person who had changed them for ever – not a noble idea or philosophy, but a person. They had met Jesus Christ and had been transformed.

Implications

That Christianity is founded on historical events has several implications. Firstly, the good news concerning Jesus Christ is for all of us – not just for intellectuals. Many of us find it hard to follow complex arguments but we can appreciate facts when we see them.

This does not mean the message is for people who are a bit ‘simple’. After all, some of the greatest thinkers have been Christians. But it does mean that God has given his light to the whole world in a way that is visible to all.

Secondly, we can believe the incredible. How could we possibly know that the holy God who made us also loves us, despite our rebellion? Or that he has disclosed his love in the self-giving life and sacrificial death of Jesus Christ?

How could we possibly know that? But listen to John speaking of Christ: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God … and the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us, and we beheld his glory’ (John 1:1-14).

What a staggering statement! The meaning is unmistakable. In that ordinary-looking human being called Jesus of Nazareth, the glorious Creator God had revealed himself. More than that – he has come among us.

Thirdly, we can respond to a person. The truth concerning Jesus Christ confronts us not as an idea in the mind but as a person in the flesh. ‘The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us’.

He came to the disciples as a person and their response was equally personal. That response led them to make him known.

Tolerance or indifference?

But there is a problem here for many. Isn’t it offensive to thrust your faith down the throats of others who are just as good as you? How can anyone say they have the truth? Isn’t this bigoted?

To be sure, bigotry and ignorance of the views of others are not Christian attitudes. But neither is vagueness – mental wooliness masquerading as clear thought. Often in our modern world, magnanimity means apathy, and the broadest minds are wafer thin. Tolerance is a cover for indifference.

Suppose you knew you had a cure for a disease. Would you conceal it from others because you didn’t want to be thought ‘narrow’?

Would it be offensive to tell people about it? Would you be bigoted if you pointed out that other remedies didn’t work and, if added to yours, would negate it?

Christians should never be rude or aggressive to those who oppose the gospel. We are to bless men, not curse them. We are to be courteous to those who cannot yet see.

But at the same time,the interests of the patient come first. And to deprive others of the remedy is nothing short of criminal. If Jesus is the light of the world, can we keep people in the dark?

Faith

To speak of historical realities is one thing – to experience their power in our lives is quite another. We need more than historical reflection.

The question is this: Granted that Jesus Christ came in the flesh, how do these facts create faith in us now? What is their significance for us today? How can we make the jump from confidence in historical facts to saving faith?

The answer is found in the experience of the first Christians.

Peter tells us that they saw Christ’s glory. They did not deduce it by argument. Nor did they feel it by emotion. They saw it.

The deeds and words of Jesus led them on. As they watched his works and heard his words they were not just left with open mouths – but with open eyes.

In other words, his works and words compelled faith. They were signs to people who wanted to know. They could not but believe.

These early Christians were both good historians and eager learners. That is why they preached the death and resurrection of Jesus in Jerusalem, the very place where the facts could be checked!

In other words, those who really want to know will ‘come and see’. Others will not. It all comes down to the disposition of the heart.

As Jesus put it: ‘it is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick’. You may have the facts and miss the glory. Jesus said: ‘If anyone chooses to do God’s will he will find out whether my teaching comes from God or whether I speak on my own’ (John 7:17).

However clear the light, closed eyes will not receive it.

Resurrection

This is especially true of the resurrection of Jesus. We may well believe the historical facts concerning the resurrection without realising its significance or knowing the risen Christ.

The power of the resurrection rests on its historicity, of course. But you can believe the latter without experiencing the former.

In fact, the resurrection is of first importance, not simply because it happened but because it creates new life for us here and now. Jesus is himself the resurrection and the life – and to know him is to live.

The significance of that is immense.

Firstly, the resurrection lights up the grave. There is light in the valley of death. Physical death (the ‘first death’) has been vanquished. Life and immortality have been brought to light through the gospel (2 Timothy 1:10).

Secondly, the resurrection lights up the cross. There is real forgiveness through his death. Spiritual death (the ‘second death’) has been vanquished. The one great sacrifice for sins has been accepted, so that repenting, believing sinners are reconciled to God.

Thirdly, there is a new creation. The Christian is a ‘new creation’ in Christ and has eternal life (2 Corinthians 5:17).

Moreover, all who are united with him by faith belong to God’s new order. As ‘new’ human beings they look for new heavens and a new earth.

‘We shall not all sleep but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet’ (1 Corinthians 15:51-52).

Response

What will be our response to God’s great activity – in history and in Jesus Christ? What should we do in the face of such an amazing person, and such amazing events as his coming into our world, his death and his resurrection?

We are to ‘come and see’. If we do, we will imitate the poet who wrote:

I stand amazed in the presence

Of Jesus the Nazarene,

And wonder how he could love me,

A sinner, condemned, unclean.

Is there anything to compare with this?