They were the glory of John Owen’s millennial dawn. With Thomas Goodwin, and countless unnamed Puritans, Owen believed that the sudden sparkling of independent churches in Ireland bore testimony to the goodness of God in the last and darkest ages of history. God was building his new temple in the midst of his enemies, they believed. And in a land long desolate under Antichrist’s dominion, Christ’s church was ‘glorious as an army with banners’.

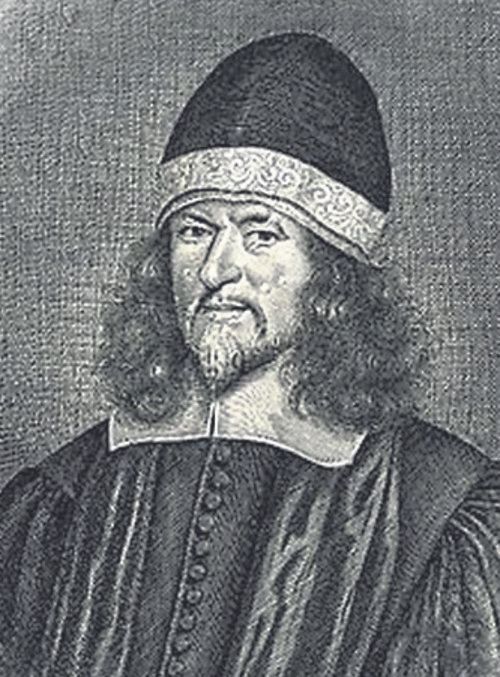

But the Independents were not the first to bring the good news to Ireland. Native Irish Protestants had been established on a solidly biblical basis by the Irish Articles, composed largely by Archbishop James Ussher in 1615. As the official confession of faith of the young Irish Reformed Church, the articles insisted on the doctrines of the gospel, but carefully avoided making demands in ‘things indifferent’.

The Irish Reformed Church recognised its need of preachers, and welcomed every faithful minister, requesting only that the episcopal basis of their church would not be attacked. As a result, Puritans expelled by the Scottish and English bishops found a congenial home in Ussher’s church.

Twin dangers

Laying the foundations of a truly Reformed ecumenicity, the Irish church gave the new arrivals every hospitality. The bishops acted as fellow-elders among the Presbyterians, rather than insisting on their episcopal ‘rights’ under church law. They thus set aside the prayer books and vestments which had caused such difficulty in the exiles’ original homes. Ireland’s ripened harvest-fields ensured that the gospel alone was the basis of its Christian unity.

Ussher’s accommodation was not always returned, however. As Ireland descended into the anarchy and confusion of rebellion in 1641, the Presbyterians became increasingly distant. The Irish church faced twin dangers. Firstly, the English king was determined to impose unscriptural rituals on the Irish church. Secondly, Ussher’s Presbyterian friends responded by supporting the Scottish Covenant and consolidating their latent anti-episcopal sentiment. With his church unity falling apart, and Roman Catholic rebels attacking his home, Ussher fled Ireland and never returned.

Decade of conflict

Ireland was ravaged by the 1641 rebellion and the decade of conflict which followed. Alliances evolved and evaporated. The situation was confusing and disturbed. The execution of King Charles sealed the decade’s most perplexing alliance, as Protestant settlers in Ulster, who had suffered so terribly at the beginning of the decade, joined with their former persecutors to swear revenge on the English Parliament.

Dominated by Cromwell’s Independents, Parliament had no alternative but to suppress this dangerous Royalist sentiment. Ironically, the Independents were republicans threatened by Ireland’s love of monarchy. They found themselves compelled to invade.

Cromwell’s subsequent military campaign has become legendary for its supposed bloodthirstiness and ethnic hatred. His real enemies, however, were not the Irish people, but an unlikely alliance of English Royalists, Ulster Covenanters and native Catholics, united in disgust at the regicide. His own troops suffered terribly throughout the length of the campaign, and reports which survive from the period complain of fevers, the conscription of aged and infirm soldiers, and the seizure of supply ships by pirates.

Ideology

Before they left England, John Owen had treated the Parliamentary troops to an apocalyptic justification of their involvement in Irish politics. ‘Ireland was the first of the nations that laid in wait for the blood of God’s people’, he claimed, so ‘their latter end shall be to perish for ever’ (Owen’s Works, viii. 231). They were the ‘sworn vassals of the man of sin’, the ‘followers of the beast’ (viii. 235). Cromwell himself believed that his Irish campaign fulfilled a prophecy made in Psalm 100.

But the ideology which fostered armed involvement in Irish affairs, also fostered the remedy needed by that troubled land-the true, trustworthy gospel of God. In a sermon in February 1650, Owen encouraged English MPs to recruit young preachers for gospel work in Ireland. In line with their Independent ecclesiology, the English MPs believed that Ireland would best be helped by the cultivation of biblically constituted Christian fellowships.

Crippled missions

Unfortunately, the missionaries came with the soldiers. In 1653, an expeditionary force of some 34,000 Parliamentary troops crossed into Ireland, with many Baptist and Independent Christians among them. Their numbers were significant; Baptists in Ireland have never since numbered more than they did during the Cromwellian period. The Baptist church still meeting in Waterford dates from this time.

The influence of these Independents was concentrated in the army. Some soldiers even complained of colleagues being ‘re-baptised’ to gain promotion. But if the soldiers were enthusiastic, their Puritan preachers were crippled by such support. The missionary expedition failed because it was so closely identified with the army.

As a result, the Puritan missionaries found it difficult to enlist any kind of cross-cultural sympathy. As part of Cromwell’s Irish campaign, they were engaged in fighting ‘Antichrist’ with every weapon at their disposal-including physical arms. Irish Roman Catholics were viewed as a threat to the English peace, rather than as sinners needing the grace of God. They were to be punished, not encouraged to seek eternal life. Little wonder, then, that documents from this period show that membership of the Independent churches in Ireland was predominantly English.

John Rogers

One of the ministers Parliament sent to Dublin was John Rogers (not to be confused with the John Rogers martyred in 1555). His church, which met in the city’s cathedral, was typical of many Independent causes. Rogers published a defence of Independent ecclesiology in 1653. This work, obscurely titled Ohel or Bethshemesh, provided a list of the characteristics his church pursued.

For example, his fellowship was grounded on the gospel alone as the basis of Christian unity. The Dublin congregation was open-Baptist, like the church which Bunyan would later pastor in Bedford. Such churches allowed into membership both those sprinkled as ‘covenant children’ and those dipped as believing adults. Rogers’ church suffered for this charity – the Waterford Baptists were severely critical of this position, and urged all those convinced of ‘believers’ baptism’ to separate from his Dublin congregation.

Rogers’ church was also keen to promote the public participation of women in public worship. Of course, their involvement was carefully restricted. It never went beyond public testimonies (‘conversion narratives’), to demonstrate that they had been saved, and so were qualified for membership in the gathered church.

But Rogers’ church nevertheless faced a sharp attack from Dublin’s only other Independent congregation for this ecclesiastical innovation. Rogers responded by quoting Joel 2:17: ‘in the last days, saith God, I will pour out my spirit on all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy’.

Apocalyptic world-view

This allusion to the ‘last days’ highlighted Rogers’ apocalyptic world-view. Ohel or Bethshemesh included extravagant eschatological claims. He argued that the sudden increase in the number of Independent churches presaged the downfall of the episcopalian and Presbyterian systems, and even suggested that the millennium would commence by the year 1700.

Rogers’ vision of the new world involved the revolution of the entire social order. With other ‘Fifth Monarchist’ groups, his church believed that society should be remodelled on a biblical basis.

Parliament seemed to concur, sending Owen and Thomas Goodwin on a mission to reorganise Ireland’s first university, Trinity College Dublin. They were ordered to suppress ‘idolatry, popery, superstition and profaneness’, and to promote ‘all due ways and means for the advancement of learning and training up of youth in piety and literature’.

Political agenda

This ‘godly rule’ thinking had a phenomenal influence throughout the Puritan movement, and undeniably contributed to the failure of Cromwell’s missionary programme. The Independent missionaries invested their evangelism with a political agenda, and publicly relied on Cromwell’s social and political elites for their support. It is hardly surprising, then, that they failed to make much impact on ordinary Irish life.

Rogers’ book contains no instances of the conversion of Roman Catholics, and no record of any attempt to take the gospel to them. With an English sword in one hand, and the gospel in another, the Independent missionaries were hardly imitating Christ.

Recovery

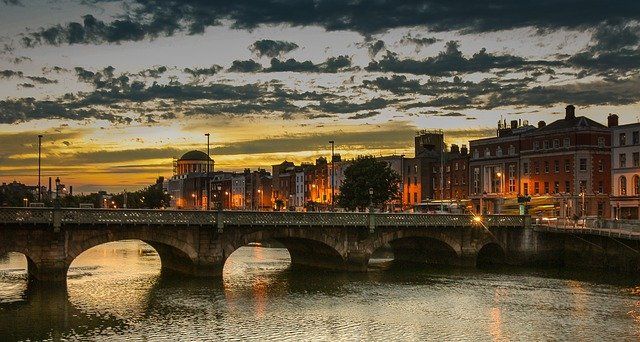

Three hundred years later, we need to learn from these lessons of the past. In many ways, Ireland’s current ecclesiastical climate is unparalleled. Within the cities especially, the Roman Catholic Church is crumbling. Spiritual hunger has been re-channelled into the materialism of the ‘Celtic Tiger’ economy or the proliferating cults.

Today, in the Irish Republic, Jehovah’s Witness ‘Kingdom Halls’ outnumber Brethren assemblies four to one. In many towns, like Galway, Jehovah’s Witnesses are the single largest religious group outside the Roman Catholic Church.

Yet there has also been a recovery of the gospel in the Irish Republic in the last thirty years. Visitors to Dublin’s three main evangelical bookshops-Scripture Union, Irish Church Missions, and CLC, find a strong emphasis on biblical and Reformed doctrine. But Ireland still needs the gospel. It is Europe’s forgotten mission field. By the grace of God, the Irish reformation has yet to begin. Let us pray, and work, that the pilgrim church might see God’s glory in a land that is ready to bloom