Features

The Federal Republic of Brazil is the largest country in South America (over 3.25 million square miles) and the fifth largest in the world. Neighbouring countries are Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Surinam and French Guiana.

Brazil is rich and diverse in natural resources. It has potential for hydroelectric power as well as large deposits of coal, iron and uranium ores. The south and east of Brazil are temperate, while the northern Amazon basin is tropical. The Amazon has one third of the world’s tropical rain forest, over 50,000 species of flowering plants (the greatest variety in the world), 20% of the world’s bird species and more than 60 species of primate.

People: The total population is 165 million. This is composed of the following races: European (53%) -(Portuguese make up nearly one third, Italian and Spanish one fifth each of this figure); African (11%); Asian (1%), mainly Japanese; Amerindian (less than 0.2%), about 200,000 in 200 tribes (once there were 5 million); mixed race (34.8 %), for example, mestizo (offspring of Portuguese/Spanish and Amerindian) and mulatto (offspring of black and white). Due to interethnic marriage none of these categories are rigid. It is claimed that up to 40% of the population is of direct or partial African descent. Portuguese is the official language. There are also many tribal languages extant.

Religions: Roman Catholic (70%) and animist (5%), with syncretism between the two; Protestant, mainly Pentecostal or charismatic (20%); others (5%), including Afro-Brazilian cults.

Economy

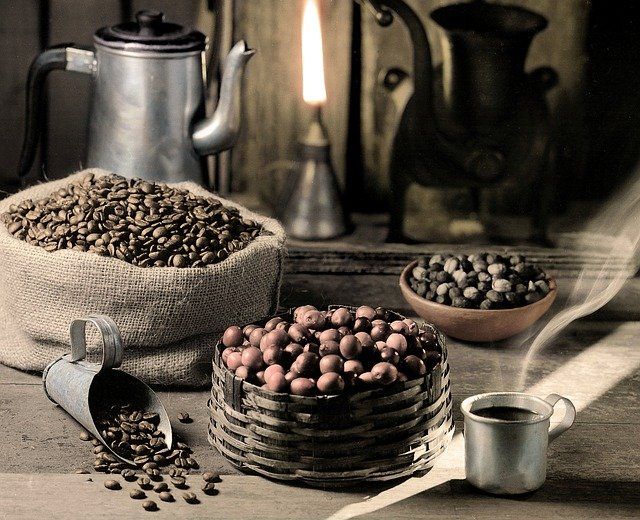

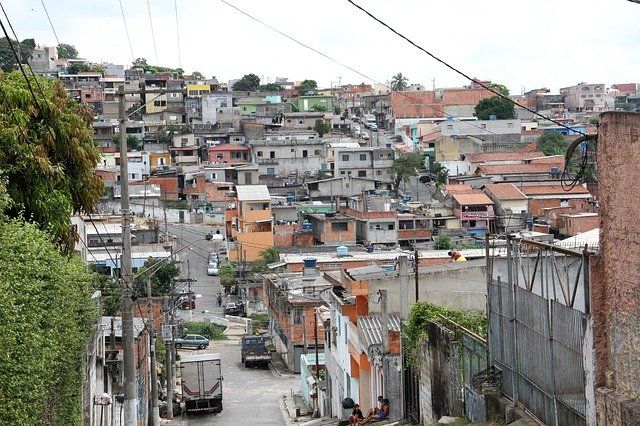

Southern Brazil is agriculturally fertile and, with the eastern coastal strip, is more heavily populated than the north. During the 1980s at least 7% of the Amazon rain forest was destroyed by settlers who cleared the land for cultivation and grazing. Rapid industrialization in the south during the 1960s and 1970s was followed by soaring inflation in the 1980s so that Brazil has a large foreign debt burden. However, more recently, inflation has been reduced to single figures and an economic recovery is under way. The average income of $2,550 per person (12% of USA) is shared very unequally between the 20% rich and 80% poor. There is a very large underprivileged class. Brazil depends heavily on agriculture both for domestic and foreign trade. Exports include coffee, sugar, soya beans, cocoa beans, cotton, textiles, motor vehicles, steel, timber, iron, chrome, manganese, tungsten and other ores, as well as quartz crystals, industrial diamonds and gemstones. It is the world’s sixth largest arms exporter.

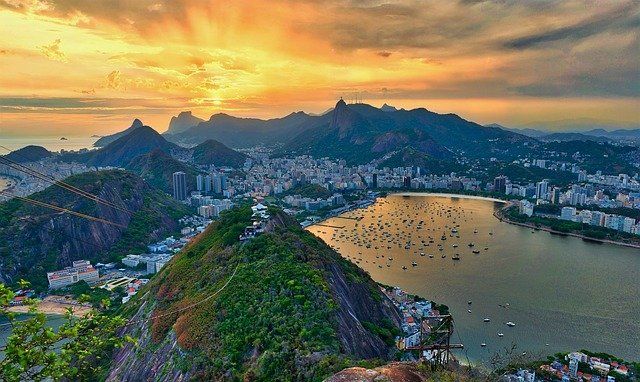

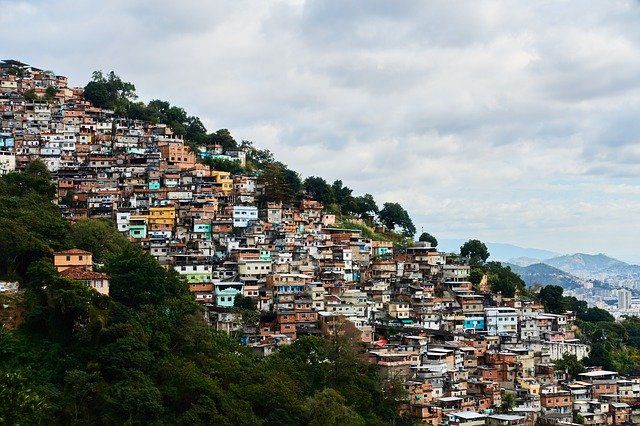

Capital: Brasilia (2 million). Major cities: Sao Paulo (18.3 million), Belo Horizonte (3.6 million), Fortaleza. Ports: Rio de Janeiro (11.7 million), Porto Alegre, Recife, Belem and Salvador.

History

Originally inhabited by South American Indians (Amerindians), including the Incas, Brazil was colonized by the Portuguese in 1500. The introduction of sugar cane from the African islands of Madeira and Sao Tome gave rise to a plantation economy on the coast. This was worked by slave labour so that, by 1800, black slaves from West Africa and Angola made up one third of Brazil’s population. Slaves were also used in mining and cattle ranching.

When in 1808 the French emperor Napoleon invaded Portugal, the Portuguese king escaped from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro. He returned to Lisbon in 1821 but in 1822 his son, Pedro, declared Brazil independent from Portugal and himself the Emperor of Brazil. During the rest of the nineteenth century large numbers of Portuguese and other Europeans emigrated to Brazil, attracted by opportunities for ranching, farming and discovering minerals and precious stones and even gold. The country developed quickly. Slavery was not abolished, however, until 1850.

In 1889 Brazil’s monarchy was replaced by a republic. After social unrest in the 1920s and a series of revolts, led by younger army officers, the republic was brought down by revolution in 1930. Dr Getulio Vargas became president and ruled as a benevolent dictator for most of the next 21 years. He expanded Brazilian industry, including its trade in coffee and rubber, and increased expenditure on state education, health and social services. Vargas was succeeded by Dr Juscelino Kubitschek, who followed a policy of economic development combined with nationalism. This led to unprecedented economic growth and culminated in the construction of Brasilia, the country’s capital since 1960.

The 1960s and 1970s brought a series of military dictatorships. By the early 1980s there was economic decline. Labour strikes followed, coupled with calls for the return of democracy. Thus in 1985 the first civilian president for 21 years was elected. In 1988 a new constitution was adopted, under which considerable power was transferred from president to congress. Measures were also introduced to halt large-scale burning of the Amazonian rain forest. After considerable political turbulence, including the dismissal of the president for corruption in 1992, the 1994 presidential election was won by the Social Democratic Party candidate.

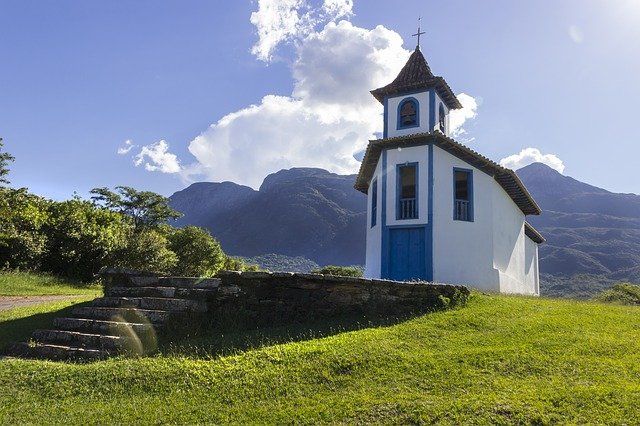

Church history

Brazil has not only been an ethnic and political ‘melting pot’, it has been a religious one. Roman Catholicism entered the country in the sixteenth century through its Portuguese colonizers. As Catholicism interacted with endemic animism the result was often syncretistic, paganized Catholicism. There were short-lived attempts to plant Protestantism in Brazil by French Huguenots in 1555 and by the Dutch Reformed in 1624, but both these were crushed by the Catholic Portuguese. Later European immigrants of the nineteenth century included Lutherans, Anglicans, Italian Waldensians and Scottish Presbyterians, yet the influence of Protestantism was largely contained within these ethnic communities.

Paradoxically the twentieth century ecumenical movement has resulted in increased Protestant mission to South America. The 1916 ‘Conference on Christian work in Latin America’, meeting in Panama, identified South America as a mission field. The end of the Second World War brought large numbers of missionaries into South America both from denominational and interdenominational missions. These have included societies whose particular object has been to translate the Scriptures and plant indigenous churches among Amerindian tribes.

Since the 1950s liberal theologians in Latin (Central and South) America have incorporated Marxist thinking into their ‘theology of liberation’. This directly equates the overthrow of agencies of political or economic oppression with the coming of the Kingdom of God. Although such teaching is met with coolness by today’s traditionalist papacy, it has found acceptance with a number of indigenous Catholic and Protestant leaders and seminaries. Brazil was once built on the back of slavery, while the ‘visible church’ was happy to support the status quo. There is continuing grinding poverty for millions, sharp economic inequalities, a heavy burden of overseas debt and the alleged ‘exploitation’ of the Amazon and its peoples. It is not surprising then that liberation theology has appealed to many.

The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), convened by Pope John XXIII, has resulted in a change in Rome’s stance compared to that of previous centuries. Overt persecution of Protestants has decreased. There is an apparent new emphasis on Bible reading and the role of the laity. However, the impact of Roman Catholic ecumenism upon Brazilian evangelicals has been vitiated by the fact that many of the latter were previously nominal Catholics, who now equate Catholicism with spiritual emptiness and idolatry. There has been a continued drop-out of Catholics to Protestant churches and a fall in the numbers of Catholic priests.

Aggressive evangelism by Protestants since the 1960’s, including the widespread use of Christian radio stations, has expanded their numbers in Brazil from thousands in 1900 to over 30 million today. The supply of leaders has not kept pace with the rapid expansion of these congregations. The bases of expansion have been particularly in the Pentecostal movement, ‘evangelism in depth’ programmes and ‘big name’ crusade evangelism.

Evangelicalism in Brazil through this century has been theologically defective. A clear proclamation of the gospel of God’s grace in Jesus Christ has been bypassed by all but a small minority of Protestants. Pentecostalism’s phenomenal growth has probably occurred more because of sociological than spiritual factors. Pentecostals have concentrated on the underprivileged and working classes, practised informal styles of worship, involved the laity and displayed a ‘flexible ecclesiology’ in church-planting strategies. All these approaches have found an echo in Brazilian character. More recently the neo-pentecostal movement has gained ground within both historic Protestant and Catholic churches. There has, in consequence, been rapprochement between charismatic Catholics and charismatic Protestants, but on the basis of shared experience rather than doctrinal agreement.

Current situation

Syncretism, or ‘mix-and-match’ religion, is prevalent in today’s Brazilian religious scene.

1. It is said that there are probably more people attending Protestant churches on a Lord’s Day morning than Roman Catholic masses, yet some 70% of the population are still, according to statistics, Catholic!

2. Traditional African religions have recently surfaced in a variety of rapidly growing Afro-spiritistic cults. Many Brazilians engage in spiritism while holding Christian ‘beliefs’. An estimated 60% are involved in some way in occult practices. Mary is portrayed as the maternal ruler of human affairs, who has an uncanny resemblance to Yamanja, Queen of the Sea an idol of Yoruba (West African) origin; God is a vague and remote controller of destiny who can be appealed to, but is otherwise inoperative; Jesus is the weak figure of Catholicism.

3. It is reported that neo-pentecostals are non-evangelical in theology and practice. They are ‘usually ignorant of any idea of grace’. The Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, numbering some 2 million members, sells holy water, holy oil and holy corn to religious seekers. Its followers are said to be ‘quietly determined’ during their services of worship to appropriate the blessings of health, wealth and personal fulfilment.

4. One correspondent to Evangelical Times says that Brazilians synthesize combinations of all the available religions. Any one Brazilian might engage in several of the following practices.

a) The practice of official Catholicism, involving mass and confession.

b) Participation in folk Catholicism, holding, with varied loyalty, to a particular ‘santos’ (saint), as identified by an idolatrous image.

c) Visits to African mediums to counter the influence of malign spirits.

d) Consulting astrologers, fortune tellers, Catholic or spiritist healers.

e) Having a relationship with a particular familiar spirit, which relationship mirrors a society where ‘who you know’ is all important and, in return for loyalty and small favours, the superior person (or ‘spirit’) does you a favour.

f) Participation in one of tens of thousands of ‘grass-roots’ or ‘basal ecclesial’ communities (BEC). Each BEC is a group consisting of 5-35 economically impoverished Catholics, meeting regularly to sing, pray and read the Bible, with little to guide them except a political agenda informed by liberation theology.

Challenges

There is much concern within the evangelical churches for the unreached. Over 1,300 cross-cultural missionaries are operating within Brazil and over 800 overseas. The peoples of north-east Brazil and the Amazonian tribal peoples remain among the least reached. However, the question must be raised: What kind of a message are these missionaries and pastors preaching? One Sao Paulo pastor has said, ‘The Brazilian [Protestant] church is not a reflective church, it is an emotional, experiential church. It does not deal with what is true and what is false, it deals with phenomena and emotions. As a result, the church is reaching those who seek feelings, and fails [to reach] thinking people who want a coherent and intelligent presentation of the faith.’ That presentation must be the teaching of the whole counsel of God in the Scriptures.

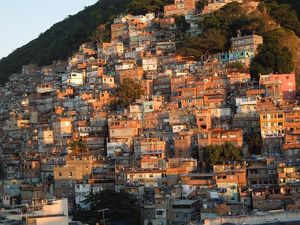

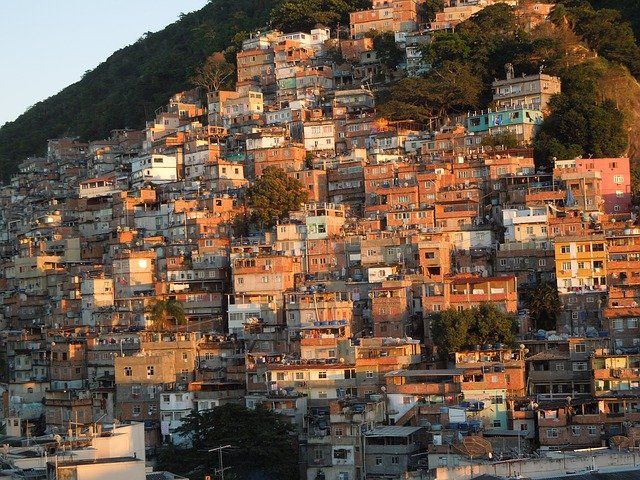

Coupled with these needs there are urgent social problems. There is widespread illiteracy. 13 million people inhabit slum areas of the major cities amid great poverty. Some of these are affected by drugs, with resultant AIDS and criminality. An estimated 8 million children live in sewers or on the streets of the cities, having lost contact with their families, a prey to drugs, prostitution and gangsters. An increasingly large Protestant community is uncertain how best to meet these social needs. Should the church pursue a political agenda for improvement through the ballot box, for example? One Brazilian pastor, reacting against this view, has said, ‘One segment [of the church] wants to respond to social needs through service, another wants [political] power … these are two opposite movements that will never make a marriage.’

The majority of Brazil’s 30 million Protestants would claim to be evangelical, with over three-quarters of them Pentecostal or charismatic. Large sections of the church seem to be in ignorance of the true gospel. This gospel centres on the exclusive claims of Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord, and is defined in those confessions that demonstrate from the Scriptures that salvation is only of the Lord. He sovereignly elects, calls and pardons sinners in accordance with his covenant of grace, which is accomplished in the redeeming work of Christ. In the same Scriptures the answer is given as to how the gospel works like leaven to purify a corrupt and unequal society. This happens as individuals are truly converted to Jesus Christ and then as they daily walk in the love of Christ.

Encouragements

It is encouraging, against this dark background, to know that there is a small but growing Reformed movement in Brazil. There has for many years been a nucleus of faithful, Bible-believing missionaries and churches there who have laboured to preach salvation by grace alone through faith in Jesus Christ alone.

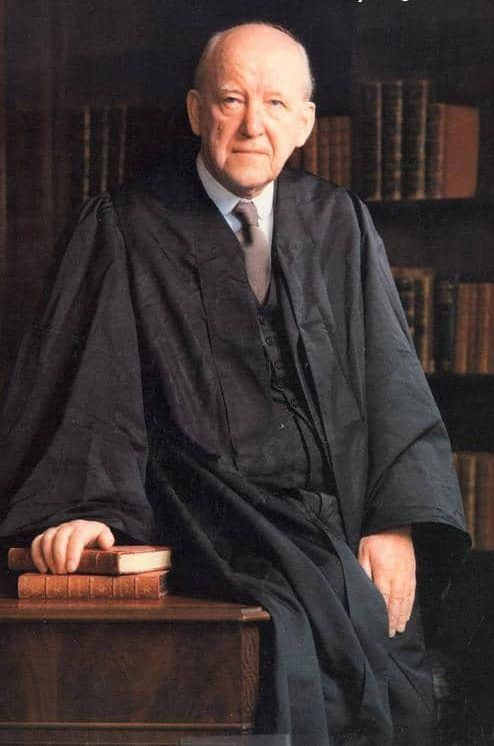

Among the agencies they have set up have been the publishing houses,Editora FIEL and PES, which have distributed sovereign grace literature across the country. Works by J. C. Ryle, C. H. Spurgeon and Dr. Martyn Lloyd-Jones are among the books published. For the last twelve years Editora FIEL has convened a Leadership Conference for Brazilian pastors and church leaders. This, as well as the Puritan conference, has been a force for reformation. A recent Evangelical Times account of the latest FIEL conference reported that among 492 registrants there were a record number of pastors and that twenty-one of Brazil’s twenty-six states were represented. Many attending travelled more than fifty hours by bus each way to attend. The programme included an address on the value of the Puritans for today and a series of four addresses on the authority, power, sufficiency and finality of the Bible.

Conclusion

A seventeenth-century Jesuit once said, with reference to Brazil’s African slaves, that Brazil had ‘the body of America and the soul of Africa’. Although slavery was abolished 109 years ago that statement remains true from a different viewpoint today. Sadly, as in much of Africa, the Protestant church in Brazil is wide-embracing yet very shallow. The evangelical community in Brazil is the third largest in the world, after those of the USA and China, but it is surely a theologically diminutive product of that same western Arminian and decisionistic teaching that it has been fed with. Until recently Brazil has been, neglected by the worldwide reformed church. There is an urgent need now to point the whole professing Christian church back to her biblical roots. In this need the church of Brazil is at one with the churches of Africa and of Western Europe. There are many millions who are ignorant of Jesus Christ in this large nation that is supposedly over 90% Christian. This is a terrible tragedy, but Brazil is not alone in experiencing it.