On 1 August 1937, five hundred people assembled for the opening of the newly-built Peking Christian Tabernacle. The threat of Japanese troops gathering outside the city could not stop the congregation attending the church’s dedication service. Peking, once known as ‘the market place of the world’s ideas’, was now a sleepy city. But within it was this strong and vibrant church.

China’s ancient wisdom had failed the nation — neither could its insurgent people solve its problems. Men still looked around for the answer.

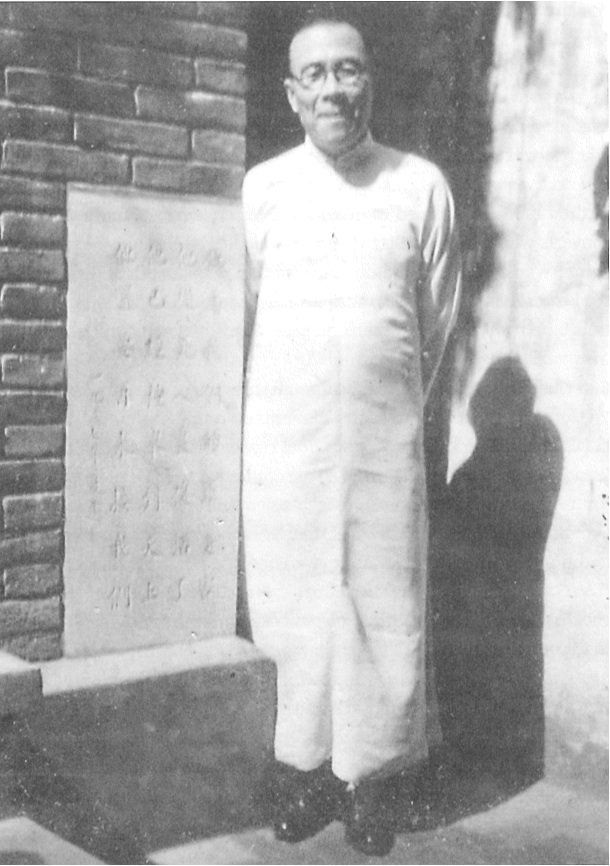

But Wang Ming Dao, the pastor of the Christian Tabernacle, had looked within himself, and there he had identified the cause of his nation’s distress. He was a man of the highest principle, yet he had found that cause to be man’s innate rebellion against God — his disinclination to obey his Creator.

God’s remedy

Wang Ming Dao knew that Jesus Christ had suffered on the cross two thousand years before. He did so to bear the punishment for the sin of those who repented of their rebellion against God and looked to Christ for forgiveness. Wang knew that revolution by the masses could not resolve man’s troubles. A nation’s hope lay at the door of the individual.

This was the testimony Ming Dao bore to his country, knowing that righteousness exalts a nation but sin is a reproach to any people (Proverbs 14:34).

But Wang Ming Dao also had a powerful message for the church. The underlying thrust of his life-long ministry was to promote virtue and purity among believers.

Rev. Thomas Wang, now an internationally acknowledged leader of the Chinese church overseas, was brought up in the Peking Christian Tabernacle. He says, ‘Ming Dao was a person whose desire was to make ideals into realities’.

In his life and service, written and spoken, at home and throughout China, Wang Ming Dao exerted untiring effort to bring about in the church consistency between word and life. To this end self-discipline occupied a significant place in his ministry.

Spiritual principles

Thomas Wang vividly recalls his own childhood memories of the pastor and his wife. ‘It was always a beautiful sight to me’, he says, ‘to see Mr and Mrs Wang Ming Dao each peddling a bicycle in the streets of Beijing (Peking) to do visitation, or on their way to a meeting’. But the real impact Ming Dao had on him, he says, ‘was his high view of Scripture, his uncompromising stance on biblical faith, and strict adherence to spiritual principles in life and service’. ‘It is Wang Ming Dao’, he continues, ‘to whom I and my family owe the foundation and discipline of our spiritual life’.

Thomas Wang also speaks highly of Wang’s wife, Jing Wun, a gifted pianist, who supported her husband in every way, even sometimes cautioning him in his ministry or in his dealings with people.

Wartime

But now in 1937, when the war that neither China nor Japan wanted was breaking out all over China, Wang Ming Dao’s ministry was restricted to the Japanese occupied zone. China’s hatred of Japan still ran high, but its own revolution was its one consuming desire. As for the overcrowded nation of Japan, it coveted some, though not all, of the land-space of China, the largest country in the world.

The Chinese war minister would always believe that Japanese military radicals were to blame for the all-out war. On their part, the Japanese claimed that it was a communist plot. It is certain that the war served Soviet interests. It diverted Japanese aggression from China’s and Russia’s bordering states and prevented Russia from being driven from the Far East.

The war also paved the way for the growth of the communist party in China. And it played into the hands of ‘spiritual wickedness in high places’.

Atrocities

Wang Ming Dao and his wife Jing-Wun had moved into the little home built for them on the spartan premises of the Christian Tabernacle. For the first time in their nine years of married life, they were free from the maltreatment they had known in Ming Dao’s family’s home. But before long their freedom was replaced by the oppression of war, a trouble more distressing than the cold looks and angry words of the past years.

As the war gathered pace, rumours of atrocities became realities. Incidents of unaccountable aggravation by the Chinese occurred. The Japanese fought savagely and without strategy. Warnings circulated that for a Japanese to kill a Chinese meant no more to him than to kill an ant. This was proved true at Nanking, at that time the capital of China. News of a massacre there, one of history’s worst, reached the world.

So, early in 1939, Wang Ming Dao knew he took his life in his hands when he ignored the occupying authority’s ruling that all periodicals must contain Japanese propaganda slogans. He had sought guidance in fervent prayer and had decided against ceasing publication of his Spiritual Food Quarterly to avoid the problem. Courageously, he sent a copy without the slogans to the Japanese. Then he waited. A prayer-answering God intervened. Wang Ming Dao heard no more. The periodical, that was to prove a tremendous source of strength and blessing to the Lord’s people in the long years ahead, continued.

Alliance

But darker days for Christians lay ahead. Japan declared war on Britain and America in 1941, and all churches set up and supported by those countries were closed. Other churches in Peking formed an alliance and looked to the Japanese authorities for help to maintain their church work.

Although the Christian Tabernacle was an indigenous church, it did not join in. Wang Ming Dao perceived that the churches had opened the door for the Japanese to impose conditions upon them by seeking assistance from the occupying power.

This did, in fact, transpire and a new, united, state-sponsored church for the occupied zone of China was formed. Within months it had appropriated and twisted biblical principles, namely, the need for churches to be self-supporting, self-controlling and self-propagating, by creating the ‘three-self movement’. This three-fold concept had been introduced to China through missionary work, but now it was put to work in the service of a corrupted Christianity. The misuse of these three principles, in different forms, was to cast a long shadow over the remainder of Wang Ming Dao’s long life.

Strengthened by prayers

The pressure to join the ‘three-self’ movement intensified. The danger of compromise threatened.

‘But how can churches which stand for the truth of salvation through faith and by grace be affiliated with associations or groups which do not believe these truths?’ Wang reasoned. He knew that a great number of church members and pastors were not true believers.

As at other times, God guided Wang by his Word. ‘What part has he that believes with an infidel?’ (2 Corinthians 6:15). He knew that to join would destroy the testimony he had borne all over China, and God would be dishonoured. It came home to him also at that time (and he preached a series on the subject) that fear was the cause of compromise and had been the reason for King Saul’s downfall.

Strengthened by the prayers of the Christians, Wang attended the summons to meet a leading Japanese official, singing a hymn as he cycled through the streets of Peking. Later he would be called to the Police Office, a place of torture and terror. He was prepared, although unnecessarily, for the worst.

Prepared for death

Although Ming Dao was in the prime of life, he adopted the behaviour of an elderly Chinese preparing for death. He arranged for his own coffin to be made. And there in his sitting room it was housed in readiness throughout that disturbing time.

But God owned the stand Wang Ming Dao had made. Having explained his position to the government official in an hourlong interview, the Japanese had shaken his hand warmly and proved that the Japanese could be both polite and reasonable as well as cruel and desperate. It was clear that he had respected Wang Ming Dao’s principled stand. He declared, ‘He is very determined, we have no means of compelling him to join’. Unmolested, the Peking Christian Tabernacle maintained its independence throughout the years of World War II.

Although the meaning of Wang Ming Dao’s infant name, Wang Ming Zi, is ‘iron’, nevertheless, strong as iron is, we know it can break. So far Wang had stood inviolate, ‘strong in the strength which God supplies’

But how would he fare when the powers of evil concentrated all their forces upon him in the days to come?