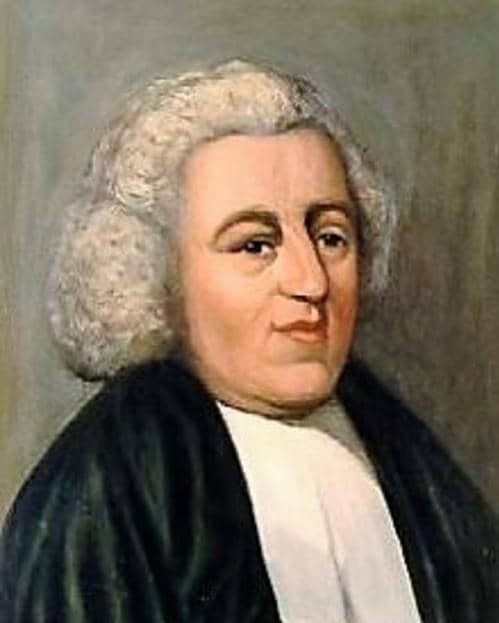

William Cowper, poet and hymn writer, was constitutionally incapable of facing the rigours of life. He had an ‘inherited mental imbalance, a physical deformity and a natural melancholic disposition’ wrote a contemporary.

The loss of five siblings, and of his mother just before he turned six, made an early impression on his sensitive mind. At Westminster City School he was cruelly bullied until the culprit was expelled.

In 1763, at the age of thirty-two, dreading an examination for the position of ‘clerk of the Journals of the House of Lords’, he made three unsuccessful attempts to take his life. He broke down completely, and was admitted to an asylum in St Albans for eighteen months. After obtaining some relief, severe depression returned in 1773, and he died in the grip of melancholy in 1800.

Marvellous insight

There is mystery attached to Cowper’s spiritual pilgrimage and the effect of his mental illness upon it. Despair brought him to Christ, and he was wonderfully converted in the asylum at St Albans.

He proved to be a spiritual and industrious Christian. In Olney, the rector John Newton regarded him as an unpaid curate. He gave himself to caring for the poor, visiting the sick, assisting with the children’s work in the church, and leading prayer meetings. He had clear evangelical views, and his prayers were always profoundly edifying. He wrote hymns that show marvellous insight into the ways of God and true Christian experience.

However, in 1773 he lost all spiritual comfort, and sunk again into despair. He continued to believe that the gospel was absolutely true, but that it was true for every single creature apart from himself. He was under the delusion that God required him to take his own life, and that he could never be forgiven for failing to do so.

Preaching his funeral sermon, John Newton revealed his own persuasion regarding the state of Cowper’s soul. He declared: ‘What a glorious surprise must it be to find himself released from all his chains in a moment and in the presence of the Lord whom he loved and whom he served’.

The man Cowper needed

For about twelve years in Olney, from Cowper’s arrival in 1767 until Newton’s departure to London in 1780, William Cowper had a most remarkable pastor. John Newton was a warm and genial man, a Church of England minister, evangelical and Calvinistic in doctrine, and exceptionally skilled in the care of souls.

William Jay was convinced that Newton was exactly the man Cowper needed: ‘Some have thought the divine [i.e. Newton] was hurtful to the poet. How mistaken were they! He was the very man, of all others, I should have chosen for him … His views of the gospel were most free and encouraging. He had the tenderest disposition; and always judiciously regarded his friend’s depression and despondency as a physical effect, for the removal of which he prayed’.

Newton and his wife, together with the church in Olney, employed every means at their disposal to help this sensitive and wounded soul.

Prayer and hospitality

Newton ministered to the poet first of all by prayer. In 1770, at the time when Cowper’s brother was seriously ill, Newton assured him: ‘Prayer is made both for him and you among us publicly and from house to house’. Another letter assured Cowper: ‘You are remembered by me, not only jointly with the people, but statedly in the family and in secret; and, indeed, there are not many hours in the day when I do not feel your absence and the occasion of it’. In a further letter he added: ‘Prayer is made without ceasing among us, for you and your brother … I have just arisen from my knees, to take the pen in hand’.

1773 saw the onset of Cowper’s deep and lasting despair. There were times when his needs were so absorbing that Newton could hardly attend to anything else. On 12 April, the annual fair day, Cowper retreated to the Vicarage to evade the noise. In the event, nothing could persuade him to leave, and John and Mary Newton cared for him in their own home for more than a year.

Friendship

Secondly, Newton was a friend to Cowper. They met while Cowper was resident with the Unwin family in Huntingdon. Morley Unwin had suffered a fatal fall from his horse. Newton was travelling home, exhausted after a long tour of the country, and visited and comforted Mrs Unwin and Cowper.

Deeply impressed by his friendship and ministry, they moved to Olney to live in his parish. They moved into ‘Orchard Side’ which was back-to-back with the Vicarage. A pathway through a hole in the wall joined their respective back doors, and Cowper would often let himself into the Vicarage and visit Newton in his study on the second floor.

Of this period Newton wrote: ‘The Lord who had brought us together so knit our hearts and affections, that for nearly twelve years we were seldom separated for twelve hours at a time, when we were awake and at home. The first six I passed in daily admiring and trying to imitate him; during the second six I walked pensively with him in the valley of the shadow of death’. When called out, Newton would visit his neighbour in the small, dark hours of the morning, devoted friendship overlapping pastoral care.

Their friendship continued after Newton moved to London. Shortly after his arrival in London he had a fall and dislocated his arm. In a letter to Cowper he used the injury as an analogy to express the sense of loss he felt, at no longer having ready access to his friend and Mrs Unwin: ‘But indeed, a removal from two such dear friends is a dislocation, and gives me at times a mental feeling, something analogous to what my body felt when my arm was forced from its socket. I live in hopes that this mental dislocation will one day be happily reduced’.

Correspondence

Thirdly, Newton ministered to Cowper by his letters. We can only guess at the wise and loving counsel that characterised their conversation, but letters in Newton’s collected works offer a tantalising glimpse of the affection, sympathy, and counsel extended to Cowper by his faithful pastor.

On 30 July 1767, shortly after Cowper’s arrival in Olney, Newton wrote encouraging him to resist the dark and discouraging thoughts that were being insinuated into his mind. He assures Cowper that God, having done great things for him, will not forsake him. He expresses his hope that they will become better acquainted, and asks for Cowper’s prayers.

In a series of four letters in 1770 he seeks to help Cowper through the anxiety of his brother’s serious illness. He reassures Cowper that the Lord is a Great Physician whose compassion is equal to his power. He will either spare his brother, or enable his brother to desire to depart, and William to resign him.

With great insight he notes that ‘trials would not deserve the name, nor could they answer the ends for which they are sent, if we did not feel them’.

Contradiction

The correspondence and sympathy continued from London: ‘when you pipe, I am ready to dance; and, when you mourn, a cloud comes over my brow, and a tear stands a tip-toe in my eye’.

He gently remonstrated with Cowper: ‘How strange that your judgement should be clouded in one point only, and that a point so obvious and strikingly clear to everybody who knows you! How strange that a person who considers the earth, the planets, and the sun itself as mere baubles, compared with the friendship and favour of God their Maker, should think the God who inspired him with such an idea, could ever forsake and cast off the soul which he has taught to love him! How strange is it, I say, that you should hold tenaciously both parts of a contradiction!

‘Though your comforts have been so long suspended, I know not that I ever saw you for a single day since your calamity came upon you, in which I could not perceive as clear and satisfactory evidence, that the grace of God was with you, as I could in your brighter and happier times’.

The efforts of a pastor

Newton used all the means at his disposal to help Cowper. Some were wise, some unsuccessful, and others, with hindsight, almost amusing. But all were pursued with the sincere desire to help.

Newton kept Cowper busy with pastoral work. Cowper’s hymn writing was all the more encouraged as melancholy set in, since it would occupy his mind with great gospel themes. Medication prescribed by Dr Nathaniel Cotton, who ran the asylum at St Albans, was used until it proved ineffective. Who knows what relief modern medication might have brought him?

Newton went on walks with Cowper. He was encouraged to garden and cared for a menagerie of rabbits, hares, guinea pigs, birds, dogs, a squirrel and a cat. Newton had an electrical contraption of which it was said by Josiah Bull: ‘it occurred to Mr Newton to try on his friend the effect of the electrical shock, and this he did, but without any salutary result’. They were the efforts of a pastor and friend trying to offer relief.

In conclusion, we have to concede that God alone can interpret the mysteries surrounding Cowper’s troubled spiritual pilgrimage and mental malady. But who, in Cowper’s condition, would not desire a pastor like John Newton?