Who was George Borrow?

You would not have asked that question a hundred and fifty years ago, for then the author of The Bible in Spain, Lavengro (Word-Master), The Romany Rye (Gipsy Gentleman), not to mention Romano Lavo-Lil (Gipsy Dictionary), was as famous as Charles Dickens.

For generations George Borrow, also known as ‘Don Jorge’, has been an enigma, and still is. What can be said of a child who could not read at six, yet (it is said) became fluent in thirty languages? Who only learned to read so that he might follow the adventures of Robinson Crusoe? The claim concerning his linguistic prowess takes some swallowing, especially when we consider his chequered childhood. Nevertheless, De Foe’s story does appear to have triggered a remarkable ‘gift of tongues’ in the young George Borrow.

He was born on 5 July 1803, at Dumpling Green near East Dereham. His father was a recruiting officer in the Army, and little George spent his early years trailing around from camp to camp. It was at Norman Cross, where his father was Adjutant, that he met Ambrose Smith (Jasper Petulengro), and was, incredibly, initiated into the Romany lore.

After an unsuccessful apprenticeship at law, and a spell contributing to Phillips’ Radical Magazine, he began to wander as a tinker, mixing with Gypsies, bruisers and every other kind of ‘gentleman’ found on the nineteenth-century roads. It was while staying with his widowed mother in Norwich that he came under the notice of the Bible Society, then in Earl Street, London. They badly needed someone with a knowledge of Manchu, the diplomatic language of China. It has been suggested that Borrow ‘put on’ religion to get the job. If so, he was a remarkable actor, for the interview board consisted of two discerning men, Revs Joseph Jowett and Andrew Brandram. There is reason to believe that George had been converted, or at least brought near to the kingdom, when he spent nine days with Peter and Winifred Williams, the Welsh Calvinists. Be that as it may, by early August 1833 he was in St Petersburg. His seven-year odyssey had begun.

Russian ‘agent’

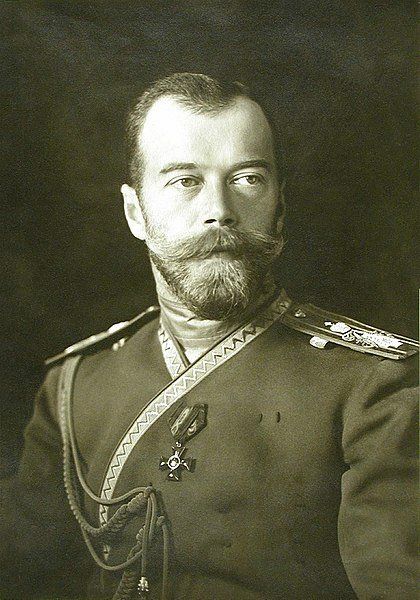

‘Tall George’, as the Russians called him, was to ‘assist Mr Lipovtzoff (a Russian civil servant) in the editing of such portions of the Manchu Testament as we choose to print. (Luke and Acts have been resolved upon already.)’ So far so good, but printing the work was a different story, for Tsar Nicholas had recently closed the Russian Bible Society. Borrow showed a remarkable singleness of purpose. Arranging everything on his own, fighting bureaucracy, and working thirteen hours a day, he pushed the project through. The Bible Society’s report for 1835 reads: ‘The printing of the Manchu New Testament in St Petersburg is now drawing to a conclusion.’ During little more than two years, Borrow had proved himself the best ‘agent’ the society ever had in Russia.

The Bible in Spain

His next commission was to assist with Bible circulation in Portugal, and he arrived in Lisbon on 12 November 1835. It was hardly the time for a visit, for Portugal was still reeling from eight years of civil war. Nevertheless, with characteristic enthusiasm, George began at once to organize Bible distribution, acting as leading colporteur himself. His methods impressed Earl Street. Brandram wrote, ‘We like your way of communicating with people, meeting them in their own walks.’ But George had his eyes on another field. On 1 January 1836 he rode off into Spain, to the work which produced one of the most singular books ever written about the Iberian Peninsula, The Bible in Spain.

Spain was in a worse state than Portugal, for it was still convulsed by the Carlist civil war. More interesting to George was that at Badajoz he ‘first fell in with those singular people, the Zincali Gitanos, or Spanish Gypsies, and was able to speak to them of Christ and His Word’. He arrived in Madrid on 26 January, and actually gained an interview with the Prime Minister. The result was not encouraging, for Mendizabel made it clear that he wanted guns, not Bibles, to put down the rebels. Spanish Governments, however, were short-lived, and by 13 March, Mendizabal had been replaced by Javier de Isturiz. George renewed his request and, thanks to the intervention of the British Ambassador George Villiers, permission was given to print 5,000 of Scio’s Spanish New Testament without notes. The Bible Society was overjoyed, and rightly so.

Can they read?

After a short spell in England, Borrow arrived back in Cadiz on 21 November, and by early April 1837 printing of the 5,000 New Testaments had been completed. It is difficult to describe the tenacity and courage of George Borrow, as he peddled the Testaments through the outbacks of a Spain where even the tough muleteers stayed indoors. Mr Brandram was cautious. ‘Can the people of these wilds read?’ he asked. George reassured him that he would also attempt to establish Bible depots in towns, but added that on his way he ‘intended to visit the secret and secluded spots among the rugged hills … and to talk to the people, after my manner, of Christ’. Ambassador Villiers helped him on his way by instructing the British consuls throughout Spain to give him every assistance.

The turning-point came when George set up a shop in Madrid’s Calle de Principe, with Despacho de la Sociedad y Estragera on its front in large yellow letters. At first business was moderate. Publicity was needed, and George supplied it by sticking up three thousand yellow, blue and crimson posters all over town. Apparently these proceedings caused some merriment in Earl Street. Unfortunately, the Spanish Government was not amused. An order was issued banning the sale of New Testaments from the shop. Don Jorge reacted by harassing everyone, from the Prime Minister down. The crux of the matter was that George had not read the correspondence from Earl Street properly, and consequently was unaware of the troubles of Lieutenant Graydon, the society’s unpaid agent in Barcelona. Graydon, a retired naval officer, was very charming, but somewhat naive. He had been distributing tracts that implied that the Spanish clergy were servants of Satan. These paper time-bombs also stated that the author was a co-agent of George Borrow.

Ordered to desist

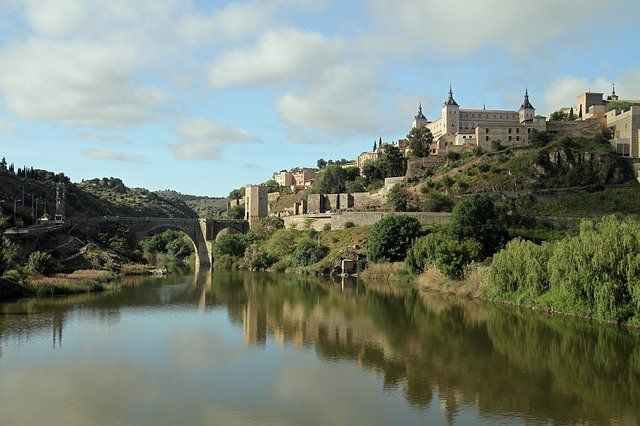

Poor George, who had always refrained from mud-slinging, suddenly found himself in the midst of a political row, which landed him in the Metropolitan Prison. This almost caused a political rupture between England and Spain, and twelve days after his arrest he walked free, completely exonerated. Earl Street recalled Graydon ‘for reasons of health’, and ordered George to cease operations. He did exactly the opposite, and set off into the nearby provinces to distribute his remaining Testaments. At Toledo he even gained an audience with the Primate of all Spain! He also had the satisfaction of knowing that the curates in two Madrid churches were expounding the society’s New Testaments to groups of children every Sunday evening.

George finally left Spain on 3 April 1840, after Palmerston had forbidden British Consulates throughout the country to render service to religious agents. During his six years in Spain, nearly 5,000 New Testaments, 500 Bibles, and a large number of copies of his Basque Gipsy Gospel had been distributed. During this time he had contracted fever, dysentry and ophthalmia. Once he had been mistaken for the dreaded Don Carlos and almost shot. He had also been imprisoned at least twice. Once he had said, ‘I hope yet to die in the cause of my Redeemer.’ He almost got his wish.