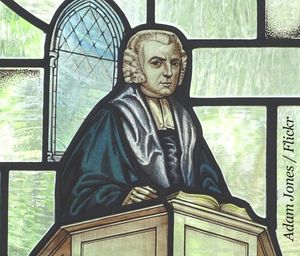

A sermon that well illustrates how justification by faith alone lay at the heart of the eighteenth-century Evangelical revival is Whitefield’s sermon on 1 Corinthians 1:30: Christ, the believer’s wisdom, righteousness, sanctification and redemption.

It was written out early in 1741 while Whitefield was on board ship on his way home to England from Georgia. It appears, however, that he had preached it various times in the preceding months on what was his second visit to America. It was published in Edinburgh in 1742, and subsequently came out in further editions in other cities in England and America.

True humility

Whitefield begins his sermon with a mini-reflection on the phrase ‘of him’, a statement which could well be translated ‘it is due to him that’. Alluding to Jeremiah 2:13, Whitefield says that God the Father is ‘the fountain from which all those blessings [described in 1 Corinthians 1:30] flow’.

Whitefield develops this theme: ‘the apostle therefore, when here speaking of the Christian’s privileges, lest they should … think their salvation was owing to their own faithfulness, or improvement of their own free will, reminds them to look back on the everlasting love of God the Father’. This doctrinal point, referred to as ‘election’ elsewhere in the Scriptures, plays an important role in the development of a biblical spirituality for, rightly understood, it promotes ‘true humbleness of mind’.

True wisdom

He then deals with the first thing that we have in Christ -‘wisdom’. True wisdom, he argues, is not ‘indulging the lust of the flesh’, a reference to the open immorality and godlessness of his day. Nor is it found in the acquisitive ‘adding house to house’. Neither is it found in merely intellectual knowledge, for ‘learned men are not always wise’.

What, then, is genuine wisdom? Well, first, Whitefield says (and here he quotes an ancient Greek maxim) it is to ‘know thyself’. What do the children of God need to know about themselves?

They need to know that before their conversion they were ‘darkness’, but that now, they are ‘light’ in the Lord (Ephesians 5:8). They know something of their lost estate. They see that ‘all their righteousnesses are but as filthy rags; that there is no health in their souls; that they are poor and miserable, blind and naked’.

And knowing themselves, they know their need of a Saviour. This knowledge is basic and foundational to any biblical spirituality.

Righteousness

It should be noted that Whitefield’s evangelical perspective ran completely counter to that of many of his learned contemporaries, such as Alexander Pope (1688-1744), who were advocates of Enlightenment humanism. In Pope’s An Essay on Man there is this famous couplet:

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan:

The proper study of mankind is man.

What polar opposites are found in the bosom of the eighteenth century – Christ-centred Evangelicalism and the man-centredness of the Enlightenment!

The type of self-knowledge that Whitefield is advocating leads logically to the realisation that we need Christ as our righteousness. Whitefield develops this thought in terms of Christ’s active and passive obedience.

By the former, Christ fulfils the entirety of the law’s righteous demands. This righteousness is imputed to the believer so that he or she now legally possesses the righteousness of Christ. ‘Does sin condemn? Christ’s righteousness delivers believers from the guilt of it’.

By the latter, Christ passively bears the punishment for the sins of the elect – he takes legal responsibility for them, so that God the Father blots out the transgressions of believers. ‘The flaming sword of God’s wrath … is now removed’.

Faith is the means

And the means of receiving these precious benefits of Christ’s death? Faith alone – believers are ‘enabled [by the Father] to lay hold on Christ by faith’.

Whitefield clearly indicates that faith itself does not save the sinner – only Christ saves. Faith unites the sinner to the Saviour. Thus faith, though a necessary means to salvation, is not itself the cause or ground of salvation.

As Whitefield says, ‘Christ is their Saviour’. Employing the text of Romans 8, he goes on to emphasise that genuine self-knowledge not only provides the foundation for a truly biblical spirituality but also gives that spirituality a tone of triumphant joy: ‘O believers!…rejoice in the Lord always’.

A little further on in the sermon, after Whitefield has dealt with sanctification (a topic dealt with in a later article in this series), he notes two errors regarding the relationship between justification and sanctification.

The one confuses these two aspects of our salvation and makes sanctification the cause, and not the effect, of our salvation. But our acceptance with God is rooted solely in Christ’s righteous work done in his life and in his death.

Though Christ is ‘made unto us … sanctification’ in a positional sense, the believer’s sanctification is always incomplete in this life in a practical sense. Sin, to some degree, still indwells him.

But acceptance with God demands perfect holiness. Only Christ’s righteousness is perfect. Therefore, when it comes to our standing before God, we need to look to Christ and his righteousness alone.

The importance of works

The second error relates to good works. Though no man is saved by works, no one can be truly saved without producing them (Ephesians 2:8-10). Whitefield rejects the error of practical Antinomians who ‘talk of Christ without, but know nothing of a work of sanctification wrought within’.

Whitefield stresses, ‘it is not going back to a covenant of works, to look into our hearts, and seeing that they are changed and renewed, from thence form a comfortable and well grounded assurance’ of salvation. If ‘we are not holy in heart and life, if we are not sanctified and renewed by the Spirit in our minds, we are self-deceivers, we are only formal hypocrites: for we must not put asunder what God has joined together’.

In other words, believers cannot be in union with half a Christ. The New Testament never says that Christians must lead holy lives to become saints. But it assumes that those who have been made saints, by faith alone, will lead holy lives.

As Whitefield rightly says, ‘We must keep the medium between two extremes; not insist so much on the one hand upon Christ without, as to exclude Christ within, as an evidence of our being his;…nor, on the other hand, so depend on inherent righteousness or holiness wrought in us, as to exclude the righteousness of Jesus Christ without us’.