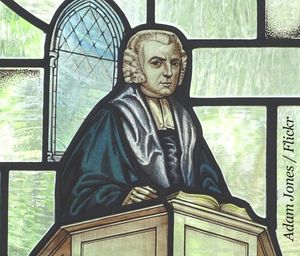

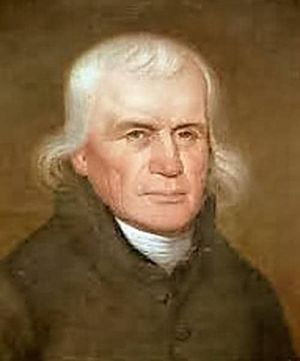

In the archives of Bristol Baptist College there is an unpublished manuscript that records a precious friendship. It was between Benjamin Francis, whose ministry we have been exploring in Parts 1 and 2, and fellow Welshman Joshua Thomas (1719-1797), who was pastor of the Baptist cause in Leominster for forty-three years.

The manuscript is actually a transcript, drawn up by Thomas, of letters that passed between them from 1758 to 1770.

Questions and answers

The practice of Francis and Thomas appears to have been for one of them to mail two or three queries periodically to the other. Then, some months later, the recipient mailed back his answers, together with fresh questions of his own.

The recipient made comments on these replies, the new questions were answered, and both comments and answers were despatched along with new queries, and so on. All in all, there are sixty-eight questions and answers in two volumes – fifty-eight in the first volume, the remaining ten in Volume II.

Only once during the years from 1758 to 1770 was there a noticeable gap in correspondence. That was in 1765 when Francis lost his wife and his three youngest children.

It is noteworthy that at the beginning of the correspondence the two friends sign their letters simply with their names or initials. However, as time passes, their mutual confidence and intimacy deepens, and they begin to write ‘yours endearingly’ or ‘yours unfeignedly’ (even ‘yours indefatigably’ or ‘yours inexpressibly’!).

It was in October 1762 that Thomas first signed himself ‘your cordial Brother Jonathan’ and, in the following February, Francis replied with ‘your most affectionate David’. From this point on this is how the two friends refer to each other.

Instructive

The questions and their answers are extremely instructive, revealing the areas of theological interest among mid-18thcentury Calvinists. For instance, the question is asked: ‘When may a Minister conclude that he is influenced and assisted by the Spirit of God in studying and ministring [sic]the word?’ (Query 5).

Queries are raised about the eternal state of dead infants (Query 17, 22); how best to understand the remarks in Revelation 20 about the millennium (Query 18); and whether or not inoculation against smallpox, the dreaded killer of the 18thcentury, was right or wrong (Query 45).

A good number of the queries relate to what we would call ‘spirituality’. In 1763, for example, Francis asked Thomas: ‘Is private fasting a moral or ceremonial Duty? and consequently is it a duty under the gospel?’ (Query 43).

When Thomas sent his response, one of his questions in return was: ‘What are the best means of revival, when a person is flat and dead in his soul?’ (Query 47).

Other similar questions were asked: ‘How often should a Christian pray?’ (Query 44, by Francis); ‘When may a Christian be said to be lively and active in his Soul?’ (Query 48, by Francis); ‘Wherein doth communion and fellowship with God consist?’ (Query 55, by Thomas).

Let us look more closely at the questions and answers that relate to prayer.

Teach me to pray!

‘How often should a Christian pray?’ To this very vital question posed by Francis, Thomas has an extensive answer.

He deals first with what he calls the ‘ejaculatory kind’ of prayer – prayers that arise spontaneously during the course of a day’s activities. He then considers prayers offered during times set apart specifically for prayer (what a later generation of Evangelicals would call ‘the quiet time’).

Addressing his friend as ‘my Jonathan’ (a reference to the bond of fellowship between the Old Testament figures David and Jonathan), Francis confesses:

‘I wish all our Brethren of the Tribe of Levi were so free from lukewarmness, on the one hand, and enthusiasm, formality and superstition on the other, as my Jonathan appears to be.

‘I am too barren in all my Prayers, but I think mostly so in Closet prayer (except at some seasons) which tempts me in some measure to prefer a more constant ejaculatory Prayer above a more statedly Closet prayer, tho I am persuaded neither should be neglected.

‘Ejaculatory prayer is generally warm, free, and pure, tho short: but I find Closet prayer to be often cold, stiff or artificiall [sic], as it were, and mixt [sic] with strange impertinences & wandrings [sic] of heart.

‘Lord teach me to pray! O that I could perform the Duty always, as a duty and a privilege and not as a Task and a Burden!’

Smoke on a windy day

In another of Francis’ comments we find the same honesty and humility: ‘How languid my faith, my hope, my love! how cold and formal am I in secret Devotions!’ (Remarks on Thomas’ answer to Query 48).

These remarks surely stem from deep-seated convictions about the importance of prayer. Francis would undoubtedly have agreed with Thomas that a believer’s ‘Great and chief delight, his meat & drinke [sic], the life of his life’ is his ‘closet prayer and communion with God’ (Query 48).

Francis’ frank remarks also arise from his belief that because the Lord had led him to Christ at a very young age – and, in his words, ‘overwhelmed me with Joy by a sense of his Love’ – he should be more eager to pray out of a sense of gratitude.

Instead, he confessed, ‘A stupid, indolent, sensual or legal Temper sadly clog the Wings of my Prayers’ (Remarks on Queries 7-8, Volume II).

Thomas sought to encourage Francis by reminding him that ‘closet prayer [is like] the smoke on a windy day. When it is very calm the smoke will ascend and resemble an erect pillar, but when windy, as soon as it is out it is scattered to and fro, sometimes ’tis beaten down the chimney again and fills the house.

‘Shall I not thus give over? Satan would have it so, and flesh would have it so, but I should be more earnest in it.’

Francis sought to pray to God twice daily, but confessed that he had difficulty in following the discipline of a set time for prayer because he was away from home much of the time.

He also admitted that he had taken up ‘an unhappy Habit of Sleeping in the Morning much longer’ than he should. And this cut into valuable time for prayer. He did not try to excuse such failings.

How much has changed since Francis’ day – and yet how much remains the same! We have the same struggle with sin and poor habits that hinder our praying and devotion.

Answered prayers

In 1767 Thomas asked: ‘How may one know whether his Prayers are answered or not?’ (Query 2, Volume II). Thomas gives six brief answers:

‘By the removal of the evil pray’d against, or the reception and enjoyment of the good pray’d for.

‘By the peculiar and extraordinary circumstances that may attend the removal of the evil or the reception of the good: as the success of Abraham’s servant etc.

‘When one does not receive the Blessing pray’d for, but receives another, perhaps not thought of by him, yet more seasonable, needful and useful.

‘When he is assisted by the Spirit to pray, to pray in Faith, and to wrestle with God. His Prayer will then be answered, whether he perceives it or no, or whether he lives to see it or no, yea tho’ he does not receive the particular good he prays for.

‘When God meets, that is, revives and relieves him in prayer, that is a speedy way in which God answers the Prayer of his People. “I will not remove thy sore affliction, Paul, tho thou hast intreated me thrice; but my grace shall be sufficient for thee to bear it”. Thus God sometimes answers a Prayer with a Promise, but not the immediate Blessing.

‘In general one may conclude that God answers his Prayers, when he is made more Holy and resigned to the will of God, and enabled to persevere in all the Duties of Religion, and to rejoice in the God of his salvation.’

Fervent prayers

The last of these six answers is especially important. It displays the mature realisation that four of the most important things for which we can pray are: (1) growth in holiness; (2) unreserved commitment to God’s sovereign will over one’s life; (3) perseverance; and (4) a heart of joy in God.

When Francis died in 1799, it is noteworthy that what his close friends remembered most, in regard to his devotion, were his ‘fervent prayers’. Given what has been noted above, this would have surprised Francis, who felt his prayer life to be so full of faults and failings. This surely indicates that often a man is not the best judge of his spiritual strengths and weaknesses.