John Thomas (1757-1801) died two hundred years ago this year, and accompanied William Carey (1761-1834) as a missionary to India in 1793.

The Baptist historian Ernest Payne once said of him: ‘no stranger figure can ever have played an influential role in missionary history’. His friends, like Carey and Andrew Fuller (1754-1815), noted that his character had a number of glaring faults — he was prone to extreme mood swings, was sometimes easily angered, had little money-sense, and was given to impatience.

William Carey, though, had been convinced that Thomas was ‘a man of great closet piety’, very compassionate in his dealings with the poor in India, and indefatigable in teaching those who were seeking for truth.

Fuller, for his part, had no doubt that Thomas’ style of preaching was well suited to India: ‘a lively, metaphorical, and pointed address on divine subjects, dictated by the circumstances of the moment, and maintained amidst the interruptions and contradictions of a heathen audience’.

Christ’s benefits

Thomas came from a Baptist home in Fairford, Gloucestershire, where his father was a deacon in what was a sturdy Baptist community. Thomas was not found by Christ, however, until he was in London, and sat under the preaching of Samuel Stennet (1727-1795), pastor of Little Wild Street Baptist Church.

His conversion came in 1781. In his diary, Thomas describes how he spent ‘many days and nights … in the enjoyment of believing that Christ had died for me in particular. Me, me, so insignificant, so worthless! That such a one as I should be a partaker of his benefits! — this thought attended me for many days, wherever I was. I had many tears of joy and gladness’.

Subsequent Christian experience, though, was for Thomas a series of emotional ups and downs, the result of his impulsive and imprudent nature. And yet, burning in his heart was an unquenchable passion to see Christ exalted among the nations.

Concern for India

Thomas had trained as a doctor at Westminster Hospital, London. When he ran into financial difficulties he decided to take the position of surgeon on one of the ships of the East India Company.

During his second voyage to India in 1786 he became friends with Charles Grant (1746-1823), an Anglican Evangelical who was on the Board of Trade of this powerful company and was based in Calcutta.

Grant helped him start a missionary enterprise in Bengal, where Thomas began to learn Bengali and to translate the Scriptures into that tongue. He also made some headway in learning Sanskrit.

He was deeply moved by the wretchedness, both spiritual and material, of many of the Indian people, and longed to alleviate it.

Carey

By 1790, for a variety of reasons (not the least of which were Thomas’ increasing financial indebtedness and mercurial temper) the friendship between Thomas and Grant soured; so much so that Grant, in the later words of Carey, ‘cut off all [Thomas’] supplies, and left him to shift for himself in a foreign land’.

Thomas, still deep in debt, had to return to England in the early months of 1792 to secure funds to undergird his missionary work in Bengal. He also hoped to find, if at all possible, a like-minded companion for the work in India.

Almost as soon as the ship had made landfall in England on 8 July, Thomas got in touch with Samuel Stennett and Abraham Booth (1734-1806), two of the leading Baptist pastors in London. He made known to them his desire with regard to a mission to India. Booth put Thomas into contact with Carey.

Pity humanity

Providentially, Thomas had arrived in England just as a group of Baptists from the English Midlands were about to form a missionary society. During the late 1780s and early 1790s, Carey had been gazing upon wider spiritual horizons than the fields of his native Northamptonshire.

He was increasingly gripped by the desperate spiritual plight of those who lived in countries utterly devoid of Christian witness. Many of them had no written language; certainly none of them had the Scriptures in their own tongues; and there were neither local churches nor resident ministers to share with them the good news of God’s salvation.

‘Pity, therefore, humanity, and much more Christianity’, he wrote in a book published in 1792, called ‘loudly for every possible exertion to introduce the gospel amongst them’.

Baptist Missionary Society

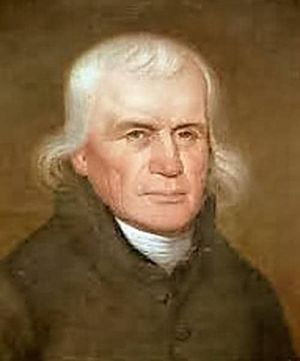

Equally persuaded of the importance of cross-cultural missions were fourteen men, including Fuller, John Ryland Jr (1753-1825) and John Sutcliff (1752-1814), who met in the back parlour of the home of Martha Wallis (d.1812), the widow of a deacon of Kettering Baptist Church, Northamptonshire, on 2 October 1792.

That day they formed what would in time be called the Baptist Missionary Society. In its early days, however, it was called ‘The Particular Baptist Society for propagating the Gospel amongst the Heathen’.

Thomas met up with these men in January 1793, and within a short period of time he and William Carey became the society’s first missionary appointees.

Depression

Thomas spent the final eight years of his life in India. His unstable character reasserted itself, and he often alternated, in Ernest Payne’s words, between ‘intense excitability and deep depression’.

His friends ‘either saw him full of cheerful and active love’, wrote Fuller, ‘or his hands hanging down as if he had no hope’. During one of Thomas’ times of depression, Fuller sought to help him in a letter he wrote in May 1796:

‘How could I weep on your account. Nay, before I write any more, I will go aside, and weep and pray for you, to him who alone can deliver your soul from death and keep your feet from falling.

‘My dear Brother, it has afforded me some consolation, while pleading with God on your behalf, that his help could fly swifter than this letter. O that before this arrives you may be delivered from the horrible pit!’

Krishna Pal

Carey eventually established himself and his family in Mudnabati, about 300 miles north of Calcutta. Thomas lived seventeen miles away at Mypaldighi. There Thomas’ house became, in the words of his nineteenth-century biographer C. B. Lewis, ‘the place of resort for all the sick and poor in the district around … The generous assistance of the compassionate missionary was never refused in any case of distress’.

In a letter that Thomas wrote during his time at Mypaldighi, he refers to this ministry: ‘I have patients from all parts, all poor and costly, but some of my sweetest moments are spent in giving them relief’.

His most famous patient would be Krishna Pal (1764-1822), the first native Indian to be reached for Christ by the Baptist mission. By this time, Thomas had relocated with Carey to Serampore, fourteen miles north of Calcutta on the west bank of the Hooghly River. It was here that the heart of the mission would henceforth be.

Baptised

Pal, a carpenter, had heard the gospel through Moravian missionaries some time before, but it had had little impact. On 26 November 1800, he fell and dislocated his shoulder. Having heard that there was a doctor at Serampore, the Indian carpenter sought out Thomas.

He helped set Krishna Pal’s dislocated arm and also took the opportunity to share the gospel with Pal.

The Indian returned a few days later to tell Thomas and the other Baptist missionaries that he knew himself to be ‘a very great sinner’. But he had confessed his sins and had ‘obtained’, he told them, the ‘righteousness of Jesus Christ; and I am free’.

Pal declared himself ready to break caste and be baptised. He was subsequently baptised by Carey on Sunday 28 December 1800 in the Hooghly River.

William Ward, Carey’s missionary co-worker, wrote thus in his diary of this baptism: ‘The chain of the caste is broken; who shall mend it?’

Fitting

The joy of Krishna Pal’s conversion and baptism was among the last Thomas enjoyed in this world. Not long after Pal’s baptism, Thomas suffered a major mental breakdown. The strain of missionary work and his medical practice were largely responsible.

By October 1801 he lay dying at the home of Ignatius Fernandez (1757-1831). Thomas had been instrumental in the conversion of Fernandez, who had been raised in a Portuguese Roman Catholic home in Macao, and whose parents had wanted him to become a priest.

Fernandez lived at Dinajpur in North Bengal, and it was there on 13 October 1801 that Thomas died.

It is fitting to remember Thomas, for he has often been judged badly by history and historians. In one recent account of Carey’s life all that is stated of Thomas is that he ‘squandered’ all of the money the two men brought to India. In this case, older studies are much more reliable.

As one of the earliest chroniclers of the Baptist Missionary Society wrote: although Thomas ‘was not without his failings, yet his peculiar talents, his intense, though irregular, spirituality, and his constant attachment to that beloved object, the conversion of the heathen, will render his memory dear as long as the mission endures’.