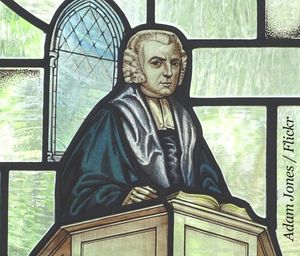

Among the Calvinistic Baptists of the late eighteenth century, one of the most important figures is also one of the least known — John Sutcliff (1752-1814), the pastor of the Baptist church in Olney, Buckinghamshire, for thirty-nine years.

Sutcliff was an extremely close friend of Andrew Fuller (1754-1815) and William Carey (1761-1834) and was one of the founders of the Baptist Missionary Society. He played a central part in bringing revival to the English Calvinistic Baptists, far too many of whose churches were somewhat moribund in the mid to late eighteenth century.

Formative influences

He was born 250 years ago on 9 August 1752, to Daniel Sutcliff and his wife Hannah, on a farm called Strait Hey, two miles east of Todmorden, West Yorkshire. The Sutcliffs, both ardent Baptists, attended nearby Rodhill End Baptist Church.

But since there was a service at Rodhill End only alternate weeks, the Sutcliffs also worshipped at Wainsgate Baptist Church, near Hebden Bridge.

Sutcliff’s parents ‘were remarkable for their strict attention to the instruction and government of their children’, and Sutcliff became acquainted with the truths of Christianity from an early age.

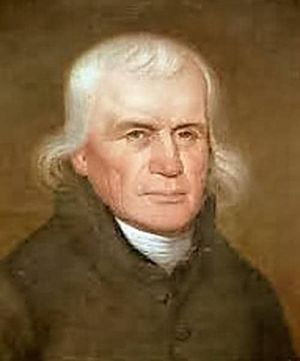

Sutcliff was converted as a teenager in 1769 through the ministry of John Fawcett (1740-1817), then pastor at Wainsgate. Fawcett himself was a child of the Evangelical Revival, having been converted under the preaching of George Whitefield (1714-1770) and shaped as a young Christian by the Anglican evangelical William Grimshaw (1708-1763).

Baptised by Fawcett soon after his conversion, Sutcliff joined Wainsgate Baptist Church on 28 May 1769. For the next couple of years, Fawcett acted as Sutcliff’s mentor, giving him both academic and spiritual instruction.

Sutcliff thus received his earliest nurture in the Christian faith from one who was very appreciative of the Evangelical Revival.

Bristol Baptist Academy

Sutcliff’s evident hunger for theological knowledge, coupled with a desire to put that knowledge into practice, prompted Fawcett and the Wainsgate Church to encourage him to pursue formal study at the Bristol Baptist Academy. This was the sole institution in eighteenth-century Britain for training men for the Baptist ministry, and he studied there from 1772 to 1774.

The principal teachers at the Academy at that time were Hugh Evans (1713-1781) and his son Caleb Evans (1737-1791), both of whom had a reputation for being evangelical Calvinists.

Caleb Evans was also a fervent admirer of the writings of the New England theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758). He strongly recommended Edwards’ writings to his students, describing him as ‘the most rational, scriptural divine, and the liveliest Christian, the world was ever blessed with’.

Evans was not the only Calvinistic Baptist of his day to be deeply impressed by Edwards. John Fawcett had read Edwards’ works in the 1760s and appears to have encouraged Sutcliff to do the same.

It is no surprise, then, that after the Scriptures, Edwards’ writings exercised the greatest influence in shaping Sutcliff’s theological perspective.

Committed to Calvinism

So great was the impact of Edwards on Sutcliff, that after the latter’s death there were some who said: ‘if Sutcliff … had preached more of Christ, and less of Jonathan Edwards, [he] would have been more useful’.

In defence of his departed friend, Andrew Fuller replied: ‘If those who talk thus, preached Christ half as much as Jonathan Edwards did, and were half as useful as he was, their usefulness would be double what it is’.

More than any other eighteenth-century author, Edwards showed Sutcliff — and fellow Baptists like Fawcett, Evans and Fuller — how to combine a commitment to Calvinism with a passion for revival, fervent evangelism, and experimental religion.

It was in the depth of the winter of 1772 that Sutcliff set out from Wainsgate for Bristol. To save money for the purchase of textbooks, he walked the entire distance, a journey of some 200 miles.

Afterwards, he often apparently travelled on foot, primarily with a view to saving money for books. Indeed, in his latter years, he had accumulated a considerable library, of which the greater part consisted of choice theological works. Andrew Fuller once described it as ‘one of the best libraries in this part of the country’.

During his two and a half years under the tutelage of Hugh and Caleb Evans, Sutcliff had an outstanding academic record. Moreover, he also had occasion to preach in various churches in the neighbourhood of Bristol, one of which, at Trowbridge, unsuccessfully sought to call him as their pastor.

Olney

Upon leaving Bristol in May 1774, Sutcliff spent six months ministering at the Baptist church in Shrewsbury, and then another six at Cannon Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

In 1775 he came to the small town of Olney in Buckinghamshire for a ministry that would last until his death in 1814.

Sutcliff was ordained on 7 August 1776. Among the Baptist pastors who took part on this occasion were John Fawcett, who received Sutcliff’s confession of faith, and Caleb Evans, who delivered a charge to Sutcliff based on Hebrews 13:17.

It was also during 1776, at the annual meeting of the Northamptonshire Association, that Sutcliff first met Andrew Fuller and soon discovered him to be a kindred spirit.

The initial years of his ministry, however, were trying ones. Sutcliff’s Evangelical, Edwardsean Calvinism deeply disturbed some of his congregation. They saw it as a departure from ‘orthodoxy’ — they appear to have had Hyper-Calvinistic tendencies — and began to absent themselves from the Lord’s Supper and from church meetings.

But Sutcliff was not to be deterred from preaching biblical truth. Matters came to a head towards the end of 1780.

Prudent perseverance

At a Church Meeting on 7 December the dissidents declared that the reason for their conduct was their ‘dissatisfaction with the Ministry’. After a long debate, it was agreed to let the matter rest for four months, and if the dissidents took their places at the Lord’s Table the matter was to be forgotten.

Although it took more than four months, Sutcliff, ‘by patience, calmness, and prudent perseverance’, eventually won over all the dissidents.

Fuller would later point to the patience and prudence he exhibited on this occasion as a prominent feature in his character.

‘Whatever might have been his natural temper’, Fuller said, ‘it is certain that mildness and patience and gentleness were prominent features in his character … It was observed by one of his brethren in the ministry … that the promise of Christ, [namely] that they who learned of him who was “meek and lowly in heart should find rest unto their souls” [Matthew 11:29], was more extensively fulfilled in Mr. Sutcliff than in most Christians’.

Six rules

Among the few extant manuscripts in Sutcliff’s own hand is one dating from the early days of his ministry at Olney. It consists of six ‘observations or rules’ that Sutcliff drew up to shape his conduct in life.

The dates when Sutcliff wrote them appear in italics after the rules themselves. They run as follows:

‘To view every thing in Religion as much as possible with my own Eyes. Let me examine for myself every text in the Bible & every sentiment in Divinity. Let me frequently read and study my Bible, as if no commentary had ever been written. 31 January, 1783.

‘To search for Truth every where in the writings of friends or foes, & seize it as my own property wherever I meet with it, & always follow evidence impartially wherever it leads me. Ditto.

‘Let me consider that every increase of religious knowledge should not only make me wiser but better; not only make my head clear, but purify my heart, influence my affections, and regulate my life.Ditto.

‘In every sermon let me have some fixed end in view and let me keep that object steadily in my eye, both in my study on the Subject and in the delivery of it. 21 November 1783, Friday afternoon.

‘Since man is a compound being of judgement and affection, let me remember that each should be addressed in the Gospel Ministry. 20 August 1784.

‘Whatever sentiment I entertain myself, or propose to others let me always put the Question Cui bono? [that is, Who benefits by it?] 25 September 1784.’