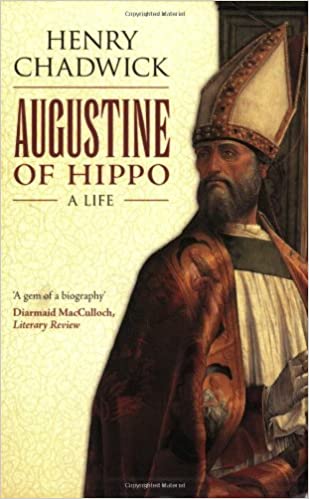

Here’s an interesting question – why should a 21st century Evangelical learn theology from a 5th century African bishop?

The answer is that the bishop knew more about God’s grace, both theologically and in his spiritual experience, than many of us. The bishop is of course Augustine of Hippo, the early Church Father whose famous conversion ranks alongside that of Saul of Tarsus.

Down through the centuries, a mighty host of Western Europe’s most godly and influential church leaders have — with others — sat at Augustine’s feet. They have found rich food for their minds and hearts in the African’s masterly expositions of God’s way of salvation in Jesus Christ.

Many of the most spiritually minded believers of the Middle Ages were disciples of Augustine — men like the Venerable Bede, Anselm of Canterbury, Bernard of Clairvaux, John Wyclif and John Huss.

Certainly the Protestant Reformers were devoted to Augustine’s vision of grace. Theologically speaking, Martin Luther and John Calvin saw themselves as doing little more than restoring Augustinian doctrine and spiritual practice to the church.

I well remember my own first encounter with Augustine. It was almost exactly a year after my conversion. For some reason now lost in the mists of memory, I decided on holiday in 1977 to read Augustine’s Confessions, his spiritual autobiography.

I had no idea what was going to hit me. My mental and spiritual universe was transformed.

It wasn’t Augustine’s theology of grace that changed me — it does not figure prominently in the Confessions. Maybe that was just as well; I might have reacted against it, since at that point my own theology was far from Augustinian.

I had no appreciation of the slavery to sin of the unredeemed human will — still less any belief in God’s unconditional election of those saved by his grace alone.

No, it was the sheer richness and intimacy of Augustine’s relationship with God that bowled me over. Here was a man who loved and revered God more than anyone I had ever known, either in person or in their writings.

Not long after that memorable encounter, I was led to embrace the doctrines about sin and grace that Augustine championed. Ironically but fittingly, this was not through reading Augustine, but through studying what the Bible said about the perseverance of the saints — which then branched out into a study of election and predestination.

I was reassured that the noble Augustine had seen these doctrines there before me, as had multitudes of others in the ‘Augustinian’ family — such as the Puritans, for whom I was beginning to feel a growing admiration.

After what almost amounted to a second conversion as these doctrines dawned on me, I immediately read a book by one of Augustine’s greatest fans — Martin Luther. The book was Luther’s Bondage of the will. It was heady stuff. Why had I never heard theology like this preached from pulpits?

Augustine was born in Thagaste in Roman North Africa in 354. He became a sexually immoral youth, joined the cult-like sect of the Manichees, and was finally converted to Christ in 386. It happened thus.

Augustine was in a garden in Milan, overwhelmed by his sinfulness, especially his slavery to sexual desire. He writes:

‘I flung myself down … under a fig-tree, where I gave free course to my tears. The streams of my eyes gushed forth, an acceptable sacrifice to You. And, not in these very words, yet to this effect, I spoke much to You: “But You, O Lord, how long? How long, Lord? Will You be angry for ever? O do not remember against us our former iniquities” — for I felt that I was enslaved by them. I sent up these sorrowful cries: “How long, how long? Tomorrow, tomorrow? Why not now? Why is there not this hour an end to my uncleanness?”

‘I was saying these things, and weeping in the most bitter contrition of my heart, when I heard the voice of a boy or girl … coming from a neighbouring house, chanting and repeating the words, “Pick up and read! Pick up and read!”

‘Immediately my attitude changed, and I began most earnestly to consider whether it was usual for children in any kind of game to sing these words. I could not remember ever hearing it before.

‘So, restraining the torrent of my tears, I rose up, interpreting the child’s voice as a command to me from heaven to open the Scripture, and to read the first chapter my gaze fell on…’

Clothed with Christ

Augustine continues: ‘I had put down the volume of the apostles … I grasped it, opened it, and in silence read the first paragraph on which my eyes first fell.

‘It said: “not indulging in revelry and drunkenness, nor in lust and debauchery, nor in quarrelling and jealousy. On the contrary, clothe yourselves with the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for gratifying your fleshly cravings” (Rom.13:13-14). I would read no further. I did not need to.

‘Instantly, as the sentence ended, a light of assurance was instilled into my heart, and all the darkness of doubt vanished away’ (Confessions, 8:28-29).

Augustine’s legacy

Augustine was baptised in 387 by the great early Church Father, Ambrose of Milan, along with Augustine’s 15-year-old illegitimate son, Adeodatus, who was converted soon after his father.

After founding a sort of monastic community in Thagaste, Augustine was ordained in 391 (against his will) as the ‘assistant pastor [bishop]’ to Bishop Valerius of Hippo Regius.

When Valerius died in 396, Augustine himself became Bishop of Hippo, a position he filled till his death in 430.

Augustine’s legacy to the church lay in the rich body of writings he bequeathed. What do they have to say to us today?

First, Augustine was one of the greatest champions of personal, experiential Christianity prior to the Reformation. His writings helped to keep alive the flame of sincere faith and godliness throughout the Middle Ages. He can have the same effect today. By far the best place to begin is his Confessions, available in many translations.

Christian thinker

Second, Augustine was a great Christian thinker. He suffered no unnatural divorce between thought and emotion — ‘mind’ and ‘heart’. Augustine loved God with his mind, not just with his feelings.

He was determined to think about his God, to bring the whole universe of his thinking into harmony with the truth of God. The best evidence of this is probably Augustine’s massive City of God, a comprehensive critique of pagan religion and a brilliant Christian philosophy of history.

We do not have to agree with all he says to be challenged and stimulated by his example. When Christians stop thinking — especially when they stop thinking in a Christian way about life at large — the church degenerates into a narrow-minded and irrelevant sect. Thanks in good part to Augustine, that certainly did not apply to the medieval or Reformation church.

Salvation by grace

Third, Augustine was the first theologian who really scaled the heights and plumbed the depths of Paul’s teaching on salvation by grace alone — especially as this teaching finds expression in the doctrine of election.

Before Augustine, this doctrine was not so much rejected as neglected. The church had not by and large thought about it. The energies of Christian thinkers were taken up with other battles.

But when Pelagianism reared its head in the early fifth century, rampant with the idolatry of human free will, Augustine responded with a stream of writings — in which he expounded the sovereignty of divine grace in salvation as none had done before him.

We cannot go along with everything Augustine says (his doctrine of baptismal regeneration should not commend itself to Reformed believers!) but the main thrust of his argument is valid, compelling in its exegesis of Scripture, and capable of illuminating, humbling and warming our hearts before God.

Augustine and the Reformers

Finally, Augustine presents us with an edifying vision of the continuity of God’s grace through the Christian ages. We admire the Reformers, and rightly so. But the church was not born when Luther nailed up his 95 theses to a church door on 31 October 1517.

Read Luther and Calvin, and you will find them quoting Augustine on almost every other page. The Reformers did not see themselves as stepping out on a new path, but calling people back to an old one.

That path was, of course, the Bible, but it was also the Augustinian tradition of theology which had never died even in the darkest medieval hour. Christ has always had his believing people, confessing that grace alone is the source of their salvation — not some combination of grace and human effort.

Knowing Augustine can help us acquire an enriching sense of brotherhood in grace, across the centuries.

Nick Needham is pastor of Inverness Reformed Baptist Church. He has recently written an introduction to Augustine entitled

The triumph of grace(Grace Publications).