During my youth, two things fought for pre-eminence in my imagination: the call of the wild and my flights of fancy on the wings of poetry.

I loved to follow in my mind’s eye the adventures of Pathfinder and the Last of the Mohicans. Even more enrapturing were the true American backwoodsman tales of Horace Kephart. Similarly, it was the adventurous tales the Land of the Wigwams in poetry of the Indians” friends Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and John Greenleaf Wittier which made my joy complete.

Few boys who have read such tales can complain that they have been bored and still speak from their hearts. Who has not been thrilled by the throbbing rhythm of courageous Hiawatha and the tom-tom beat of Nauhaught, the Indian deacon who strove to put ‘a convert’s faith’ before ‘Indian lore of evil blending’?

Whilst writing Hiawatha, Longfellow knew that there was one thing lacking in his hero’s life. It was that which he treasured most himself – peace with God. He therefore preached to the American Indians and spoke to his own soul in his poem in words as from God:

I will send a Prophet to you,

A Deliverer of the Nations –

Who shall guide you and shall teach you,

Who shall toil and suffer with you.

If you listen to his counsels,

You will multiply and prosper;

If his warnings pass unheeded,

You will fade away and perish!

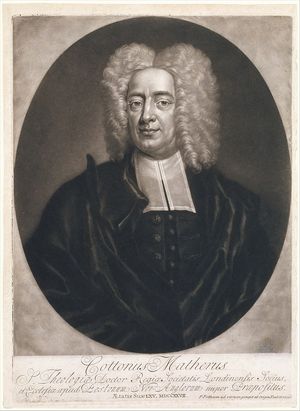

Both Longfellow and Wittier knew that God had sent a number of messengers of deliverance to the Indians. The Essex schoolmaster John Elliot pioneered the work and David Zeisberger with his Moravian friends followed him. American-born Jonathan Edwards and his son of the same name also toiled for God under the shadow of the totempoles. Nevertheless, one name, that of David Brainerd, stands out above all others as the youngster who followed the call of the wild because it was God’s call. He lived to die bringing the gospel to the Indians. His testimony shows him to be Longfellow’s ideal Hiawatha and this is how I have always viewed him.

David Brainerd (1718-1747) of Connecticut was of British Puritan stock, his ancestors having come over with the earliest settlers. Heziekiah Brainerd, David’s father, was a King’s Councillor but died whilst David was a small child. His mother Dorothy, a minister’s daughter, left her son an orphan at the age of fourteen. David was a sickly, melancholy child, often convicted of sin. At the age of thirteen a severe epidemic plagued his town and David felt he would die without having made his peace with God. This drove him to read Janeway’s Token for Children which made him strive to follow Christian duties without knowing Christ.

After working on a farm, David went to study under a minister, Mr. Fiske, who encouraged him to read the Scriptures and follow Christ. He made many friends amongst serious young men and believers and they met regularly together for prayer and mutual exhortation. Mr. Fiske died and David still confused Christianity with being ‘consistent in religious duties’. It was whilst performing these duties in 1738 that David received a deep sense of the wrath of God, his fine opinions of his own efforts fled and he felt sure that God’s vengeance would overtake him. He was now plagued continually with an inner voice telling him that it was too late, he had done his worst and could not now be saved. On 12 July 1739 on a Sunday evening, light dawned. After half an hour of duty prayer, a sudden sense of unspeakable glory flooded his heart and all his fear and apprehension fled. It was a new and mighty experience and as fast as his fears disappeared, he was filled with unspeakable joy. David saw God no longer as a ‘do this or die’ taskmaster but says, ‘My soul was so captivated and delighted with the excellency, loveliness, greatness, and other perfections of God, that I was even swallowed up in him, at least to that degree that I had no thought that I remember at first about my own salvation, and scarce reflected that there was such a creature as myself.’

Brainerd became a student at Yale but was again seriously ill. This time, he could trust in God in the face of death. After recovery, he made excellent progress at college but his efforts to witness did not always reflect godly wisdom. Once, when talking to a friend, he was asked what he thought of a certain tutor named Mr. Whittesley. ‘He has no more grace than this chair,’ answered Brainerd. This news flashed through the college like lightning and soon Brainerd was called before the disciplinary committee at Yale and ordered to make a public confession and ‘humble himself before the college’. He refused to do this and though he was first in his year and about to receive an honours degree, he was expelled with no recognition of his scholarship whatsoever.

Months of depression followed but Brainerd was gradually pulled out of the doldrums by an awareness that whilst he was overcome by self-pity, heathens were dying in their sins. He thus obtained a licence to preach and received an opportunity to witness to the Indians. There was an immediate thirst for the gospel in their reception and Brainerd grew in grace in proportion to the fruits he harvested. His prayer life strengthened and he was filled with joy at being counted worthy to draw men to Christ. The news of his success spread and soon the Scottish Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge requested details of his Christian experience and calling with a view to appointing him as their missionary to the Indians. Brainerd was interviewed and asked to preach. He felt such a sense of his own vileness, ignorance and unfitness for the task that he wondered why the society was bothering about him. Brainerd’s examiners saw only a man sent from God with a zeal for souls and promptly appointed him to his life’s work.

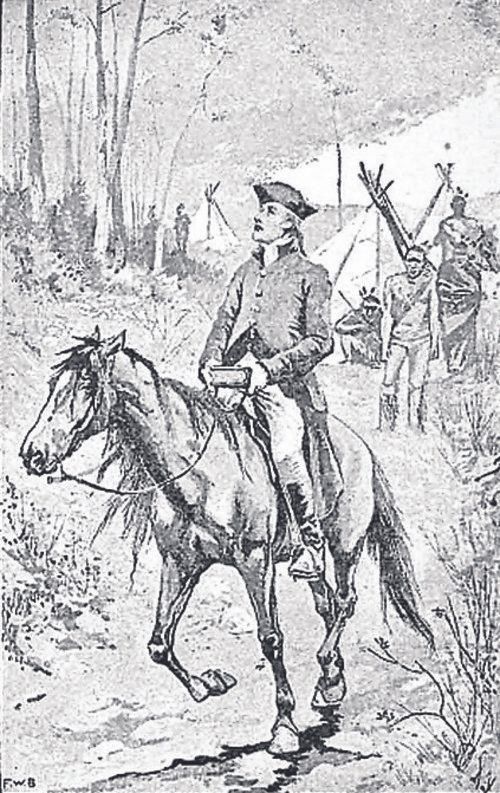

Brainerd sold all his inherited property, giving the proceeds to a penniless theological student. Then, forsaking all, at a time when Palefaces and Redskins were at war and life was always in danger, Brainerd set off to track down the Indians in the dense forests of Kaunaumeck and on the shores of the Delaware. At first he felt that Christ was hiding his face from him and he was often completely exhausted and ill from the hardships of the wild and from riding literally hundreds of miles at a stretch. Bivouacking in the summer woodlands may seem romantic to some, despite mosquitoes, grizzlies and the odd scalp hunter, but sleeping out in the winter outback was a nightly duel with death.

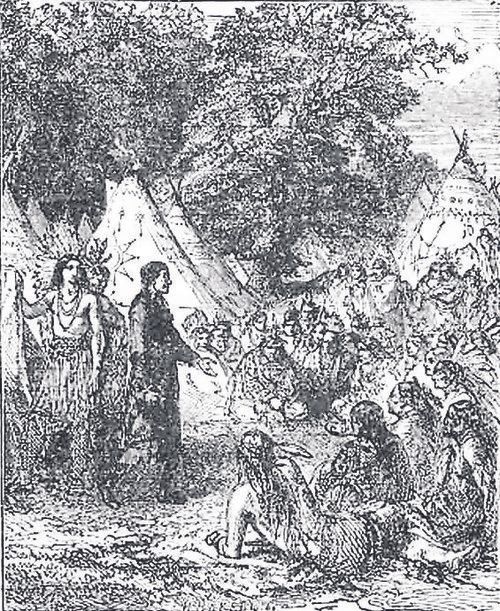

Just as he was beginning to think that the chances of converting the Indians were as black as midnight, he felt moved to disturb a well-attended pow-wow and preach the gospel to the prancing medicine-man and his braves who, instead of martyring Brainerd on the spot, stopped in their tracks to listen in amazement. After this experience ‘a most surprising concern’ was shown by the entire Indian population along the banks of the Susquehannah and the Spirit of God came down upon them like a rushing mighty wind. Soon the very old and the very young, drunkards and warrior braves were all crying out for mercy and the forgiveness of sins. White men who came to scoff were caught up in the work of the Spirit and remained to pray with their Redskin brethren. The Deliverer of the Nations had come. Soon a widespread cry went out to God: ‘Guttummaukalummeh weehaumeh Kineleh Ndah’ – ‘Have mercy upon me and help me to give you my heart.’

Brainerd found it difficult to teach the Indians sound theology as they had no Christian culture to lean on. In particular the doctrine of redemption was foreign to their ears as they had no legal system to speak of, and the idea of someone being condemned, forgiven and acquitted was quite new to them as was commercial language such as being bought with the blood of Christ. This came at a time when even some Christians with Puritan and evangelical roots were giving up the biblical language of debt, payment and surety.

Brainerd kept to the language and truths of the Bible, demonstrating total depravity by convincing the Indians that they had no need to teach their children to lie and rebel as they did so by nature. As the Indians treasured gold, Brainerd taught them how the more precious things have the greater purchasing power and how debt, which they understood, could be accrued and settled before leading them to the redemption which is in Christ Jesus. Actually, Brainerd did not need to rationalize with the Indians much at all as, during the times of revival which he experienced, conviction and salvation came hand in hand with expounding the Word of God. Brainerd was astonished at the results and could only give the explanation, ‘God himself was pleased to do it.’

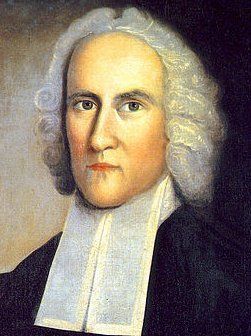

As light spread, Brainerd increased his efforts. He confessed, ‘I am in one continual, perpetual, and uninterrupted hurry, and divine providence throws so much upon me that I do not see that it will ever be otherwise.’ Though plagued with illness and bodily weakness, he remained faithful to his calling until severe tuberculosis began to slay him. In May 1747, only just twenty-nine years of age, we find Brainerd approaching Northampton, propped up on horseback, to visit his friend Jonathan Edwards and consult Dr Samuel Mather. The Christian physician examined the young preacher’s pain wracked frame and shook his head. ‘You have not the least chance of living more than a few months’ was the sober diagnosis.

How would Brainerd take the news? His next diary entry reads, ‘My attention was greatly engaged and my soul so drawn forth, this day, by what I heard of the exceeding preciousness of the saving grace of God’s spirit, that it almost overcame my body in my weak state.’

Brainerd was so caught up with the wonders of Christ’s love that life and death were secondary to him. Instead of taking to his bed and awaiting the end, Brainerd mounted his horse and, crying that there was no rest for the Christian until he rested in heaven, he continued his life-bringing preaching to the Indians, hardly dismounting from the saddle until his triumphant departure from this life came in October 1747.

Jonathan Edwards, in whose home Brainerd died, preached the funeral service on the subject, ‘True saints, when absent from the body, are present with the Lord.’ The New England pastor, who had also, as Brainerd, seen great revival under his own ministry, ended his heartfelt tribute with the exhortation to posterity, ‘Oh that the things that were seen and heard in this extraordinary person, his holiness, heavenliness, labour, and self-denial in life, may effectually stir us up to endeavour that in the way of such a holy life we may at last come to so blessed an end.’