John Paterson and Ebenezer Henderson

These two nineteenth century missionary trail-blazers lived almost nomadic existences for an extensive part of their lives, travelling thousands miles across the expanses of Scandinavia and Russia.

They were driven on by holy compulsion to spread the gospel through the translation, publishing and distribution of Bibles and tracts, in the diverse languages of those countries. Their tireless labours spawned Bible societies and evangelical societies throughout these lands.

Haldanes’ seminary

John Paterson was born into a poor home in Old Kilpatrick, near Glasgow, on 26 February 1776 and was the third child in the family. He was raised by godly parents.

As a child, he received a modest education, and in 1798 entered Glasgow University to improve his education. His salvation came through the ministry of James Haldane and he started to preach almost immediately.

From the time of his conversion, he had a growing conviction that he was called to be a missionary. He prepared himself by entering Robert Haldane’s theological seminary in 1800 for two years of study.

In 1803, he moved to Cambuslang and founded a church, but, in 1804, his calling to be a missionary was realised when the Haldanes invited him to become a missionary and join William Carey in India.

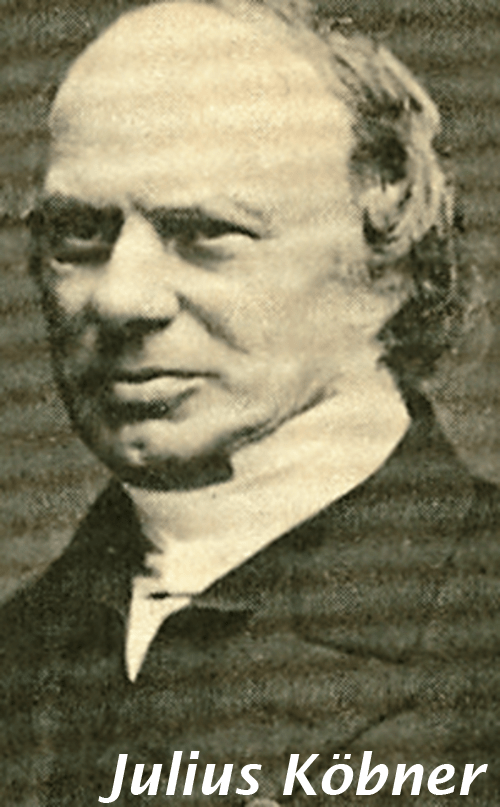

Ebenezer Henderson was born in Dunfermline on 17 November 1784. He was the youngest child of a farm worker and received only three years of schooling.

Coming from a poor background he was soon compelled to earn a living. He tried his hand at watch-making and boot-making before returning home to be a shepherd. He experienced the saving power of the gospel during a visit by James Haldane in Dunfermline.

The hospitality of the Haldanes afforded him a place in their seminary in 1803. It was in the seminary that Henderson met Paterson and received a call to join Paterson in India.

Opposites

Paterson and Henderson were opposites but, in God’s wisdom, complemented each other. Paterson was unflinching, vigorous and unsophisticated, a man of action rather than words.

He has been described in this way: ‘No particular refinement or elegance could be traced in nature. He was concise in speech and not a very good speaker. His native Scottish sharpness, not to say shrewdness, made it possible for him to thoroughly understand and adapt to new conditions and shape them according to his will’.

Henderson, on the other hand, was studious and meditative, with an extraordinary gift for languages. Mainly through his own efforts, he learned 19 languages, including Hebrew, Greek, French, German, Syrian, Ethiopian, Russian, Arabic, Tatar, Scandinavian languages, Persian, Turkish, Armenian, Manchu, Mongolian and Coptic.

Their departure for India and Serampore was planned for 29 August 1805. Armed with a letter of introduction from Andrew Fuller to William Carey, they boarded a ship at Leith bound for Denmark.

As the East India Company refused to carry missionaries on board their vessels, the two were forced to re-route for India via Copenhagen.

But Copenhagen was as far as they reached, for here they were unexpectedly delayed. By divine intervention an unplanned sphere of service in that very place began to unfold.

Theological liberalism had, by then, pervaded the Lutheranism of Denmark and Scandinavia and this both troubled and galvanised Paterson and Henderson into action. They borrowed an auction room in Copenhagen and here on Sundays set about preaching the Word.

After three weeks, they were drawing around 100 people. They recognised that an open field of opportunity lay before them and abandoned their plans to go to India. The financial aid they received from Edinburgh gradually dried up, but they remedied this by supporting themselves through teaching English in wealthy Danish families.

Bibles

Their gospel work was soon to take on another new turn, as the translation and distribution of Bibles and tracts became a new focal point for their ministry. They became zealously concerned that the Scriptures should be made readily available to all, for Bibles were in short supply and few could afford them.

They moved into Bible distribution, with the British and Foreign Bible Society (now the Bible Society) making them their agents. This society financed the printing of Danish Bibles.

The Religious Tract Society offered their valuable help by printing and covering the cost of translated tracts and the Danish Evangelical Society emerged during their two year stay in Denmark as an organ for Bible and tract distribution.

This approach to mission was hitherto unknown and innovative in Scandinavia, but one that developed through the initiative of Paterson and Henderson.

These two hardy men then left the shores of Denmark crossing the Kattegat and arriving in Sweden in 1807. Henderson moved to Gothenburg and Paterson journeyed to Stockholm, where he presented his vision for Bible and tract distribution in Sweden. In the meantime, he preached in the French Reformed Church.

In Sweden their work gathered even greater momentum. Paterson inspired the Swedish Evangelical Society in 1809 for the spreading of Bibles and tracts. And, in Gothenburg, Henderson formed a church, although Swedish nationals were legally barred from worshipping in any other church than Lutheran ones, according to the 1726 Act of Uniformity.

Both men set about translating Scripture portions, as well as tracts written by Philip Doddridge, Andrew Fuller, John Angell-James, and others. Though Paterson may not have had the intellectual capacity of Henderson, he still managed to translate portions of the Bible into eight languages.

With their baggage filled with Bibles and tracts, they set off through Sweden into Lapland, Norway and Finland, and covered at least 2,000 miles while distributing their literature.

Tsar Alexander

Their work in Sweden lasted until 1812 and did much to pave the way there for revival and the Nonconformist movement of which the Scottish Methodist George Scott was to become a leading and influential figure.

A further visit by Paterson to Finland in 1811 gave rise to the Finnish Bible Society. Finland was annexed to Russia and permission was needed from Tsar Alexander to set up the Bible society. He not only granted permission, but offered his services as its first patron.

In 1812, a new dawn arose for the labours of John Paterson and Ebenezer Henderson. Paterson was sent to Russia by the Bible Society on a fact-finding mission with a view to starting a society there as well

He arrived in Moscow and met up with Robert Pinkerton of the Bible Society. After consultation, he returned the same year to Sweden and Helsingborg to draw up plans for Russia with Henderson and Steinkopf (Bible Society secretary).

Soon back in Russia, his plans were forwarded to the Tsar through Prince Galitzin. Alexander gave his full approval to the proposals. He was delighted with the success of the Finnish Society and in 1813 authorised the formation of the St Petersburg Bible Society. Prince Galitzin became its first chairman in its inauguration in 1813.

Thanks to Tsar Alexander’s generosity, the society was provided with a spacious building that housed a printing press, storage space and accommodation for the Patersons and their staff. Bibles were printed and distributed throughout the Russian empire and auxiliary societies mushroomed.

Paterson and Henderson’s love for Sweden never waned and they periodically returned, retaining an interest in the gospel’s progress there. Paterson briefly returned in 1814 to establish the Swedish Bible Society.

In Petersburg Henderson and Paterson gave themselves unconditionally to the Russian work, undeterred by the enormity of the task of reaching the vast empire. The Petersburg Society changed its name to the Russian Bible Society and became a blessing to millions.

But by 1825 its influence was waning. The Tsar’s tottering political power and death and the hostility of state and Orthodox church threatened the society’s existence.

Accolades

Henderson returned to Britain in 1825 to take up a post as tutor, at the London Missionary College, Hoxton. He was also appointed secretary of the Religious Tract Society, before becoming tutor at Highbury Missionary College until 1850.

Henderson’s linguistic skills gained him many accolades. He was an acknowledged authority in Hebrew, referred to, for example, by Spurgeon in Commenting and commentaries and in Jamieson, Fawcett and Brown’s commentary on the Minor Prophets.

He was made honorary doctor of theology at the University of Copenhagen, doctor of philosophy at the University of Kiel, and a member of the Swedish Royal Academy of science and literature. This illustrious man of God entered glory in 1858 aged 74.

John Paterson returned to Edinburgh in 1827 and became secretary, for Scotland, of the London Missionary Society. He was made honorary doctor of theology at the University of Turku, in Finland. He passed into glory in 1855 aged 79.

These two men, through their combined ingenuity, resolution and love for God, made an outstanding contribution to the growth of the kingdom of God across Scandinavia and Russia.

David Whitworth