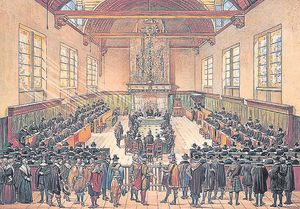

A church meeting is taking place in Smyrna. A resolution is passed. For the annual church outing we shall go to the local cemetery.

Last February the church had lost its beloved pastor – Polycarp had died a martyr at the hands of the persecuting Roman authority. Now the congregation decides to meet at his grave every year on the anniversary of his death, which took place in A. D. 155 or 156.

This plan for an annual celebration is no mere sentimentality. It is training for others who will have to suffer likewise for their allegiance to Christ.

Immovable rock

Some unbelievers in Smyrna claimed that the proposed annual gathering proved that the church was going to start worshipping Polycarp. The church exposed this as an absurd idea: ‘They do not know that we shall never be able to abandon Christ, who suffered for the salvation of those who, in all the world, are being saved, the blameless one for sinners, nor to worship someone else. For we fall down before him: he is the Son of God; but we love the martyrs as disciples and imitators of the Lord’.

Many years previously another pastor had described godly Polycarp as a man ‘fixed as on immovable rock’. He certainly proved the truth of this assessment on the day the church now plans to remember.

A few month’s after Polycarp’s death his congregation wrote an account of the martyrdom. They were glad to emphasise that it was ‘a martyrdom according to the gospel’. They meant that Polycarp’s sufferings resembled Christ’s Passion in a number of ways.

Betrayed

The account begins by noting that Polycarp waited for betrayal, just as the Lord had done. He did his best to avoid capture until he knew it was the right time.

Polycarp’s congregation could still remember an embarrassing incident when one, Quintus, came forward for martyrdom of his own accord. However, when he saw the wild beasts he lost his nerve and agreed to sacrifice to the Roman gods. To give yourself up like that is contrary to the teaching of the gospel, they said.

It was Smyrna’s pagans who set in motion the events leading to Polycarp’s death. They chanted for his arrest on the grounds of his ‘atheism’; that is to say, he did not worship their gods.

Once the hunt for their pastor was under way, the members of the church persuaded him to leave town and stay with friends on a nearby farm, and later to move on. Polycarp used this time to intercede for the work of the gospel throughout the empire. In the end a relative betrayed his whereabouts to the police.

The hour of departure

It was a Friday evening when the police finally tracked Polycarp down. They found him about supper time in an upper room. Jesus too was arrested after the last supper, which had taken place in an upper room.

Polycarp asked for time to pray before being led away. This request was granted, and he prayed for two hours to the astonishment and embarrassment of his captors.

The policemen who went to seize Polycarp brought their usual weapons, as though they were acting against a robber. Similarly, the Lord had challenged the crowd who arrested him with the words, ‘Have you come out as against a robber with swords and clubs to take me?’

The Gospels emphasise the solemnity of the moment when the hour came for Jesus’ ‘departure’ – a metaphor for his death. The account of Polycarp’s martyrdom echoes these words.

‘The hour for departure came’ the next morning. It was ‘a great Sabbath’ – which probably meant that this Sabbath coincided with one of the Jewish festivals. If it was Saturday 23 February 155 it would have coincided with Purim. If it was Saturday 22 February 156 it would have been the Passover. The day after Jesus’ crucifixion was the Sabbath of Passover week and the Feast of Unleavened Bread.

Condemned

Polycarp, like Jesus, was led into the city on an ass. He was taken to the police captain (whose name, ironically, was Herod) and transferred to a carriage. At one point the captain bustled Polycarp out of the carriage so that he grazed his shin. Without turning round, Polycarp walked on ‘as if he had suffered nothing’.

The proconsul and the police captain tried to persuade Polycarp to save his life by saying ‘Caesar is Lord’ and sacrificing to the Roman gods. At first Polycarp was silent in response, just like Jesus before the Sanhedrin, Pilate and Herod.

As they continued to pile on the pressure, Polycarp frankly refused ‘to repent from better to worse’ by denying Christ.

As he entered the arena there was uproar. The mob gave vent to its anger and castigated him as ‘the destroyer of our gods’. He was condemned to be burned to death. He responded: ‘You threaten with the fire that burns for a time, and is quickly quenched, for you do not know the fire that awaits the wicked in the judgment to come and in everlasting punishment’.

Polycarp was tied to the wood. The fire was lit. A little later the executioner stabbed his body with a dagger, and a stream of blood flowed out. So Jesus’ side was pierced with a spear and blood and water came out.

Famous words

Despite the traumatic loss of their pastor, the church of Smyrna was very clear that it had all happened according to the will of God – ‘We must take great care’, they insist, ‘to attribute to God the authority over everything’.

In the course of his conversation with the authorities, Polycarp had spoken his most famous words – words that illustrate his courage and challenge all Christians to remain true to the Lord, whatever we may be called to endure.

Polycarp said, ‘For 86 years I have been Christ’s servant, and he has done me no wrong. How can I blaspheme my King who saved me?’