This is the second part of a 2 part series.

Part 1 is here

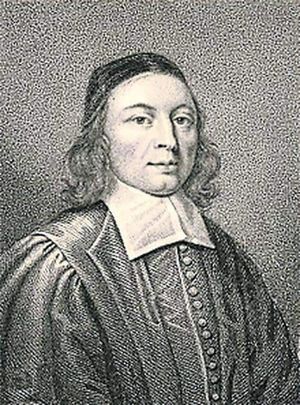

William Carey — a light for India (2)

After arriving in Bengal as a pioneer missionary (August ET), William Carey took paid employment in Mudnabati, learning to extract dye from indigo plants.

His Christian employer allowed him time for study and preaching in the surrounding 200 villages, where up to 500 would gather to listen. But these listeners were ‘low caste’, which made them resistant to change.

By spring 1797, Carey had translated all the New Testament into Bengali, but he still waited for the first conversion. He felt his preaching had become a mere formality.

On seeing his enthusiasm for the newly installed printing press at Mudnabati, the natives thought it must be the white man’s idol!

Opportunities

God opened a door of opportunity through an invitation from the Governor of Danish Serampore to establish a Protestant church in the settlement, along with schools and permission to print and publish Scriptures.

William Ward, a printer and editor from Derby, and Joshua Marshman, a master at the Broadmead Baptist School, in Bristol, had come out in 1799. They all arrived by boat at Serampore on 10 January 1800.

Joshua and Hannah Marshman opened boarding schools, which provided the major source of income for funding the printing of the Scriptures. Carey’s two eldest boys, Felix (15) and William (12), helped Ward in the press, as they were able to speak Bengali and Hindustani fluently.

Felix was saved later that year, and the following day preached in the open air. Ward said he ‘never heard a message better fitted for India’. William also soon came to faith.

A carpenter and Hindu guru, Krishna Pal, came to Thomas to have his dislocated shoulder set, and took away a tract in the form of a Bengali chant:

Sin confessing, sin forsaking,

Christ’s righteousness embracing,

The soul is free.

This verse met his deepest needs and he became their first native convert, being baptised with Felix on 28 December 1800. This was no light decision, as 2000 people had recently gathered to curse Krishna Pal and cast him in prison. He was only saved from death by the intervention of the governor.

Marshman’s free translation of Krishna Pal’s hymn is still sung today:

O thou my soul forget no more

The Friend who all thy misery

bore:

Let every idol be forgot,

But, O my soul, forget Him not.

Bengali New Testament

On 5 March 1801 the first Bengali New Testament was printed. It had taken Carey 7½ years of toil. He despatched 100 copies to Ryland, together with a case of butterflies!

A month later, Carey was petitioned to become the first professor of Bengali at the new Calcutta Fort William College, established by the Governor-General, Lord Wellesley. His being a Nonconformist, however, required that his title be changed to Tutor.

Soon, assembling a team of pundits, he initiated the publication of books which would become the foundation of modern Bengali literature. Teaching Sanskrit was also added to his duties, and on the college’s speech day, Carey had to address the Governor-General and his brother, the future Duke of Wellington, in that language.

In 1806, Carey asked for and was granted equality with the Hindustani professor, whereupon his salary was doubled to £1,500 per year. He also received the title of Professor. All his surplus income he passed on to the mission.

His Bengali dictionary had 80,000 words and was praised by the Oxford don, Professor H. H. Wilson, as exhibiting a correctness only obtainable through Carey’s long domestication among the people.

Carey’s wife Dorothy died at Serampore on 8 December 1807. In the following year, on 9 May 1808, he married Charlotte Rumohr, daughter of a Danish count. She had a physically weak constitution, yet took oversight of the education of Hindu girls. She was very caring, especially to the blind and lame.

Carey’s vision now enlarged from Bengal to the whole sub-continent of India with its many languages. The first task was to translate the Bible into Hindustani. Then there was the need to learn the other languages and produce types for previously unprinted languages. Additionally, a Sanskrit Bible would enable scholars to translate the Bible into many derivative Asian languages. The Sanskrit Bible was completed in 18 years.

Spreading light

Carey’s Calcutta chapel was built in a red-light district, surrounded by grog shops and brothels frequented by sailors.

Their church communion had, under Fuller’s insistence, been strict, fencing non-Baptists from the communion table. But this proved an embarrassment when evangelical Congregational and Anglican friends were visiting. To them they later opened the table.

Johannes Lassar from Macao arrived at Serampore and began Chinese classes, which led to Marshman’s Chinese Bible in 1823. In 1806, Henry Martyn was inspired to go to India as a military chaplain, after hearing of Carey’s work from Charles Simeon.

On arriving, Martyn was surprised to find 150 sitting at the Serampore mission’s tables and declared the Brahmin converts ‘a miracle as convincing as the resurrection of Christ’.

In 1807 Carey was awarded the degree of DD by Brown University, USA. He now also had Burma, Malaya, Nepal and Tibet in his sights, and appealed for 40 new missionaries.

Felix went to Rangoon; Carey charged him to study the Burmese language’s construction, its accents and idioms. He was to compose a grammar, frequently use the language, and start translating Mark’s Gospel. But he was appointed an ambassador, with 50 attendants and a gold sword.

Felix withdrew from the mission and became worldly, to his father’s grief, but later rejoined. Carey’s third son Jabez went to Amboyna (Ambon Island, Indonesia).

In 1810 there were 105 converts in Serampore, bringing the total to 300. By 1812, Serampore had eight printing presses, printing in 15 languages; there were translations ready in 18 languages.

Eventually, Carey and his Indian pundits were responsible for the translation of the entire Bible into six Indian languages — Bengali, Oriya, Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi and Assamese — and of parts of it into a further 29 languages.

Having studied the role of education in the Reformation, Carey’s team established a college at Serampore in 1819, providing a 7-year course in a broad range of subjects taught in Bengali.

The daughters of Marshman and Ward established ten free schools for Indian girls — a unique provision, as Hinduism forbade the education of females.

At this time, when a certain Rajput Raja died, his 33 wives were burned alive with him! Slavery was rife — 9 million were brought from East Africa to fill the harems of the Mohammedans and zenanas of the Hindus — and was not made illegal until 1843. Such was the prevalent darkness.

Dark clouds

A great fire at the Serampore printing works occurred on Wednesday 11 March 1812. It spread from the paper store and destroyed priceless manuscripts and dictionaries, grammars and Bibles.

It reduced the premises to a shell and melted newly cast types. But the damage of over £10,000 was soon subscribed and news of the disaster actually increased interest in Carey’s work back at home.

A darker cloud now arose from within the mission. Most of the original home committee had died, being replaced by younger men who had never met Carey. They gave too much credit to ill-founded rumours and sought to restrict the authority of Carey’s team. This the senior missionaries in the field resisted.

Some of their younger field colleagues, including Carey’s nephew Eustace, decided to break away and begin a similar work in nearby Calcutta. The whole episode caused Carey more heartache than any other difficulty in his life, and took many years to resolve.

Carey was a man of two books, the Word and Works of God. He avidly collected vegetable, animal and mineral specimens, and studied horticulture and agriculture, recording his observations in separate books for each subject.

His five-acre garden at Serampore was laid out on the Linnaean system, and he planted a noble avenue of trees, known as Carey’s Walk, where he would pray and meditate.

He founded the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India in 1820, open to all nationalities. Lord Hastings became patron and added an experimental farm to the Botanic Garden. All this formed a model for the Royal Agricultural Society of England (1838).

In 1823, Carey was elected a member of the Horticultural Society of London and of the Geological Society, and also a Fellow of the Linnaean Society.

Sunset

In October 1823 a great flood of the Damodar river destroyed Carey’s house and submerged his garden, devastating his botanical treasures and leaving a deep deposit of sand everywhere.

Carey was carried from his tottering house with a fever and damaged hip. Thinking he would die, he chose Psalm 51:1-2 as his funeral text and comforted himself by repeating the line, ‘Hangs my helpless soul on thee’, meditating on the value of Christ as an atoning Saviour.

Eventually he recovered and immediately set about reinstating his garden. But in 1831 a cyclone felled some of his noblest trees that had escaped damage by the flood, crushing his splendid conservatory.

Apart from Bible translation work, William Carey planted 26 gospel churches. He had founded a college and many other schools, a hospital for lepers and an institution for the poor of Calcutta.

As he lay dying, he said to Alexander Duff, ‘You have been talking about Dr Carey, Dr Carey. When I am gone, say nothing about Dr Carey — speak about Dr Carey’s Saviour’. For his memorial, he just wanted two of Watts’ lines:

A wretched, poor and

helpless worm,

On thy kind arms I fall.

Carey died on 9 June 1834, at Serampore, where he is buried.

Nigel T. Faithfull

Sources:

Carey, Eustace, Memoir of William Carey, DD, Jackson & Walford, London, 1836 (http://books.google.com).

Marshman, J. C., The story of Carey, Marshman and Ward, J. Heaton & Son, London, 1864.

Pearce Carey, S., William Carey, Carey Press, London, 1923 (8th edn. 1934).

Smith, George, The life of William Carey, DD, John Murray, London, 1887.

Stanley, Brian, ‘William Carey (1761–1834), orientalist and missionary’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.