Roman Catholicism came to this part of South America during the sixteenth-century Spanish conquest. Evangelical Protestantism only began to make noticeable inroads after the 1840s. Calvinistic and Presbyterian missionary influences were quite prominent in those small beginnings, with input from both the United States and Britain.

Church growth

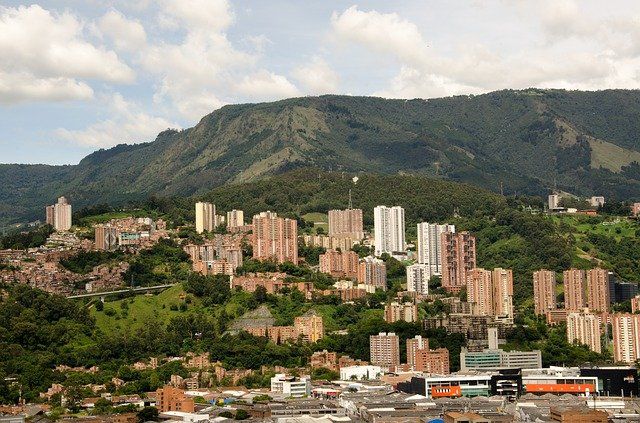

Since the 1950s significant growth has occurred in the Evangelical community. This has had some general effects on Colombian society, including the fact that Christians have founded political parties and become members of traditional political groups. The influence of Jaime Ortiz Hurtado, former Rector of the Seminario Bíblico de Colombia (Medellín), on the political and legal scene in Colombia should not be underestimated.

During these years new churches and denominations have been founded, some by missionary societies from abroad and some by national workers without links to such bodies. Various Evangelical associations have emerged. There has also been church-planting activity among indigenous groups, as well as a developing interest in mission beyond Colombia’s borders.

Church membership in Evangelical churches in Colombia has probably increased more than three-fold since the second half of the 1950s, although the rate of church growth is small in comparison with other Latin American countries. Balancing such statistics is the fact that there is a high ‘turnover’ of those professing faith in Christ and later deserting the churches.

Churches

Very few churches hold to a full-orbed Reformed theological position, although the majority are conservative in other ways and do concentrate on certain aspects of biblical teaching. Church life and worship generally follow patterns imported by missionaries but modified by Colombian culture.

Weekly activities include Sunday morning services, Sunday schools, weekly praise and prayer meetings, house groups, women’s meetings, youth groups, and so on. Many churches have all-night prayer meeting, or vigilia, which they hold quite regularly (some complain that more singing than praying takes place!).

Too often, preaching can be manipulative in style. This is an aspect of an authoritarian type of leadership which some pastors exercise. Such leaders have fallen into the traditional approach of the parish priests, so prominent in past Colombian society.

Political leadership at the local level has tended to be tyrannical. This style of leadership is known as caudillismo and I have heard theological students argue that this is the only type of leadership the majority of people understand. In recent times there has been a welcome and increasing emphasis on the role of pastoral teams made up partly of lay people. The Medellín seminary has a vital role in encouraging biblical preaching and a ‘servant attitude’.

Violence

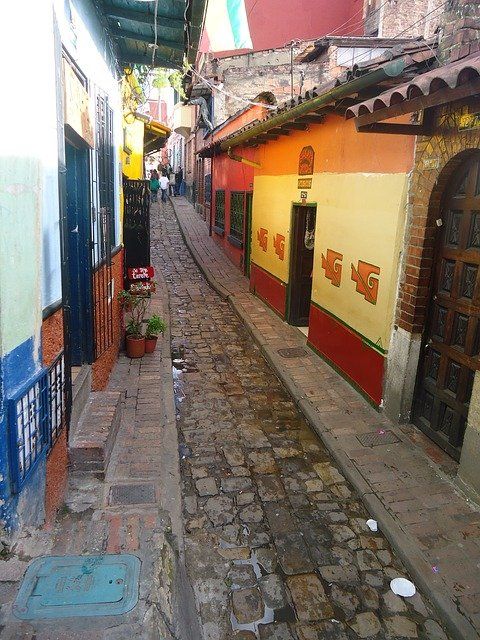

Within the often-turbulent context of Latin America, Colombia is infamous for its violence. It is described as having la cultura de la muerte (the culture of death). In fact, for complex reasons, an unofficial civil war prevailed in the country from 1948-1958, manifesting a social, political and economic struggle that dates from the start of the century.

There are parallels in the current serious conflict, which involves government, the military, paramilitary and guerrilla forces. However, apart from this specific struggle, poverty and other socio-political factors have spawned a general atmosphere of violence.

In 1990, Hector J. Pardo, a pastor in Bogota, wrote of the secondary effects of la cultura de la muerte in Colombia — effects in the country’s economy and public order, and in the daily life of citizens. He reported an increase in phenomena such as migration to the cities, the appearance of shanty towns, unemployment, family disintegration among the middle and lower classes, and the emergence of organised begging. The pressing nature of the situation was reflected in the statistic that ‘every three hours a child younger than ten is lost, robbed or abandoned’.

This violence directly affects Christians, either as members of society caught in the crossfire, or as believers persecuted because of their faith. An e-mail I received recently from Colombia reports that, according to the same Hector Pardo, over twenty-five Evangelical pastors have been killed and up to 300 churches closed in the past six months, as Colombia’s violence has escalated. The majority of the murdered pastors were from the Assembly of God churches.

Responses

How are the churches to respond in this violent context? It is rather too easy for us to theorise about all this when we do not face the daily reality of la cultura de la muerte. But there have been three responses.

The first, that of radical liberation theology, has been to advocate participation in the ‘class struggle’, which includes taking up arms against the government if necessary. The second, common among conservative Evangelicals, has been to argue (on good, biblical grounds) that the end does not justify the means. There is a danger here, however, of implicitly justifying the status quo and its violence against the oppressed.

Thirdly, some Evangelicals, belonging to what has become known as the Radical Discipleship Movement, have pleaded for active non-violence and practical identification with the oppressed. The particular responses that churches adopt will affect the way they carry out evangelism and pastoral work.

One way or another, there is much to be said for those Latin American Evangelicals who have called for an approach that is ‘prophetical, reconciliatory, pedagogical and consolatory’. The challenge for the churches in Colombia today is to minister the gospel of grace to a society facing breakdown, and to do so with biblical realism and unambiguous compassion.