Had Billy Graham’s life ended before September 1949, he would have died virtually unknown. But, the Christ for Greater Los Angeles rally changed all that. Billy called it a ‘watershed’.

From the success of those meetings, Graham and the team embarked on more than a half century of ministry, bringing the gospel to more people in more nations than anyone in history.

Billy Graham seems to me to have been a sincere, humble and gifted follower and preacher of the Lord Jesus Christ, of unquestioned moral integrity, loving and lovable.

As well as some extraordinary success, the rest of Billy’s life includes controversy. Some critics said his ministry was ‘not of God’; some admirers seemed to disapprove of any criticism at all. A balanced approach is needed.1

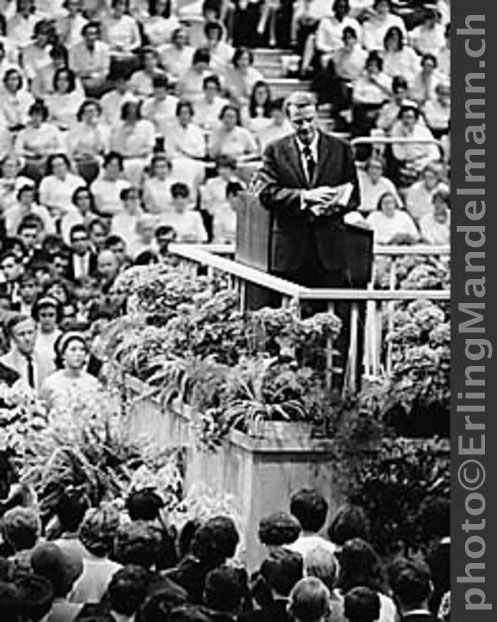

Crusades

‘Crusade ministry’ would be Graham’s major form of evangelism for his whole life. He received an average of 8,000 plus invitations each year to hold crusades.2 Curiously, the largest crusades for attendance were all outside the US, except for New York City (NYC) in 1957.3

In the authorised video biography, God’s ambassador, we are told that 83 million attended the crusades (much larger estimates have been given), with 3.2 million responses. That response figure (3.5 per cent) conflicts with the average number of responses in Graham’s crusades given by biographer William Martin (1.5 per cent). Whatever the actual figures, the numbers are huge. And even if only 1 per cent of that 3.2 million were truly converted, that makes 32,000 people.

The invitation system has always been a problematic aspect of crusade evangelism for Reformed people. Many have argued against it, for example Dr Lloyd-Jones (see his book, Preaching and preachers). But, Graham felt he was called to this type of ministry. He said: ‘My gift seems to be from the Lord in giving an appeal to get people to make a decision for Christ. That seems to be the gift. Something happens that I cannot explain. I have never given an invitation in my whole life when no one came’.4

Calling upon people to make an immediate outward response to the gospel inevitably placed the emphasis where Billy’s theology put it, on man’s will and actions; more so than on God’s sovereignty and grace.

It was also an emphasis that could bypass the crucial need for a changed heart. Of course, people could be saved through crusade evangelism, and many undoubtedly were. But it was inevitable that some people left crusades thinking they were saved simply because they went forward to make their ‘decision’; and others left unclear as to what had in fact happened to them.

Also, the follow-up of enquirers presented issues, including sending enquirers back to their own churches regardless of those churches’ understanding of the gospel or commitment to the Bible.

Fabulous fifties

In some ways the 1950s were the height of Graham’s successes. While his ministry continued to grow in future years, he never duplicated the amazing expansion that took place in the 50s.

And, I think it is fair to say that, during this time, Graham was at the height of his spiritual powers as a preacher. He would say later that both the Harringay Crusade in 1954 and NYC Crusade in 1957 took something out of him physically, something he never got back.

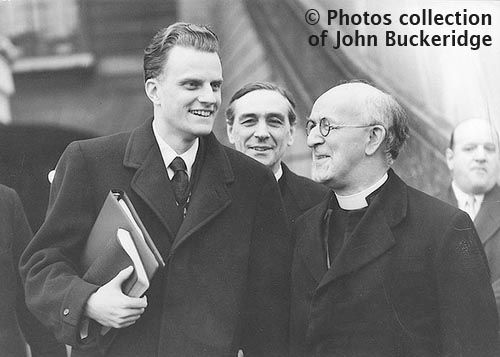

He came to London at the invitation of the Evangelical Alliance, with most churches and virtually all the press sceptical or hostile. But the 12-week crusade turned out to be hugely successful in terms of numbers, and many would say spiritually successful as well.

Two million attended the various meetings. There were 36,431 decisions recorded. But, the British weekly, a backer of the crusade, concluded that ‘the main impact was among already sympathetic church members’.

The percentage of ordinands for Church of England ministry in the London area who identified themselves as evangelicals increased considerably after this period. Remarkably, at the 1966 London Crusade, 52 men who had been converted during the 1954 crusade and had later become Anglican ministers were on the platform with Dr Graham. Whatever the real spiritual impact of Harringay on Britain, the positive impact on the ministry and the reputation of Billy Graham was enormous.5

The next landmark crusade was New York City in 1957. Over two million attended, with 55,000 responses recorded. It went from 15 May until 2 September, Labour Day, with a huge rally, approaching 100,000, in Times Square.

The crusade was broadcast on TV on Saturday nights, with a weekly viewing audience of 6-7 million. This transformed Graham’s ministry, with letters pouring in at 50,000-75,000 a week. Approximately $2.5 million was received during the crusade.6

Though he began his ministry as a ‘pure-bred Fundamentalist’7, the NYC Crusade marked the final break between Graham and his Fundamentalist supporters. This was due to Graham’s policy that a majority of all Protestant churches should support any crusade, even if they denied essential Christian teaching. The invitation he finally accepted was from the Protestant Council of the City of New York, an affiliate of the ecumenical National Council of Churches.

At a meeting of the National Association of Evangelicals, a month before the NYC crusade was to begin, Billy gave a robust defence of his ministry and its ecumenical direction: ‘I would like to make myself clear. I intend to go anywhere, sponsored by anybody, to preach the gospel of Christ, if there are no strings attached to my message’.8

Ecumenism

There is no question that Graham’s attitude towards ecumenism changed as the years went by. His early position was summed up by him in an article in The Northwestern pilot, April 1951: ‘We do not condone nor have fellowship with any form of modernism’. Yet, eventually, he was willing to work with almost any professing Christian church, regardless of its doctrinal position.

How this change came about remains a matter of some speculation since Graham never clearly addressed it. His biographers mention some factors. First, his contact with warm-hearted Roman Catholic clergy and liberal Protestant ministers convinced him they were good people, who must also be genuine Christians.9

The other factor was Harringay. He saw that, though he accepted the participation of liberals, God seemed to bless the crusade. William Martin believes that Graham’s original intention was to keep ‘free from Modernist contamination’ but the success of Harringay and other crusades helped to change his mind.10

Of course, Billy Graham’s own passion to preach the gospel to as many people as he possibly could would have been a powerful factor, since working with ecumenical churches probably meant even more people at the crusades to hear the message.

Another critical factor was the influence of his father-in-law, Nelson Bell, who ‘was partly responsible for this change’, according to Ruth’s biographer. Nelson Bell was an evangelical, but in a Presbyterian denomination (PCUS) that contained both liberals and evangelicals. It is significant that Billy later claimed he ‘never took a major step without asking [Nelson Bell’s] counsel and advice’.11

Whatever the reason, his changed ecumenical stance seems an enormous error of judgment. It may have increased numbers at the crusades, but it probably weakened the overall spiritual impact of his ministry and, over time, the health of the church. It also undermined the clarity of the gospel.

One critic said: ‘[By] not making war on some things he has gone to the other extreme, and made peace, not with the doctrines of apostasy, but with those who preach the doctrines of apostasy. This, I believe, is deadly and will one day defeat the whole cause for which this man of God is labouring’.12

Other highlights

Another feature of Billy’s ministry which began in the 50s was his involvement with politicians (see ET, May 2018). Most of his biographers have recognised some error of judgment in this. Even Billy in his autobiography says, if he had it to do over again, ‘I would also avoid any semblance of involvement in partisan politics’.13

He met every president from Truman to Trump and came to know most of them well. It was his connection with Nixon that proved the most difficult. Nixon had professed faith at the age of 13. In Graham’s autobiography, Billy comments regarding Watergate, ‘I wanted to believe the best about [Nixon] for as long as I could. When the worst came out, it was nearly unbearable for me’.14

There were other initiatives to come in later years. There were the world congresses on evangelism, first in Berlin in 1966 and then in Lausanne in 1974, the latter being much more of a world congress, with greater participation from non-Western nations.

His trips to communist countries to preach the gospel began in the 1960s, culminating in an extraordinary crusade in Moscow in 1992, after the fall of the Soviet Union. The crusades went on in locations all around the world, year in and year out, sometimes as many as 25 or 30 in one year, sometimes as few as three or four. Another highlight was preaching to an estimated 3.2 million in South Korea in 1973, the largest of Graham's crusades.

As the unofficial national leader of US Christianity, at 82, Billy was asked to address the congregation and the nation at the National Cathedral on 14 September 2001, after the terrorist attacks of 9-11. That was one of his last major acts. His last crusade was in NYC in 2005 at the age of 87. His wife, Ruth, died two years later aged 87.

In the years that followed, Billy largely receded into the background, and his son Franklin, in 2000, became the public face of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association — its main preacher and the chief executive officer.

Yet, when asked in 2005 by talk-show host Larry King how he wanted to be remembered, Billy replied, as he had on other occasions, that he wanted to be remembered as one who was faithful to the gospel.

Legacy

It’s surely too soon to give a definitive assessment of Dr Billy Graham’s life and ministry. But any fair evaluation would have to include the many souls won to Christ, the many organisations he founded or helped, and the impetus he gave to evangelistic work around the world.

Billy Graham leaves behind him an evangelicalism that is larger, and that appears more confident, less hostile to the world, and (perhaps mainly in America) ‘a beleaguered minority no longer’, as one of Graham’s American admirers put it.

But, sadly, it is an evangelicalism that is almost certainly weaker and lacking the doctrinal clarity of former generations. This is surely, at least partly, a consequence of the ecumenism which Dr Graham came to model and espouse during his ministry. If men who rejected central doctrines could be embraced as fellow workers, how important were those truths?

Perhaps one problem for Billy Graham was his seemingly never-ending ability to see the best in others, sometimes to the point of naivete. Martin has said: ‘Billy always found fewer faults in his friends than others managed to see. If they liked him, he liked them and was inclined to think the best of them’.

By the 1960s he lacked a definite position on the creation-evolution question. By the 1990s he was welcoming the existence of women preachers. He also made some well-known statements in later years that sounded like his thinking had changed, for instance, on the need for conscious faith in Christ for salvation. At the very least, he had lost some former clarity of mind. The Graham organisation has attempted to put those concerns to rest. But, questions remain. As biographer David Aikman says: ‘Billy Graham’s [theological] views, as demonstrated by his own words, did change, often in substantial ways, as his long life proceeded’.15

Yet, when asked in 2005 by talk-show host Larry King how he wanted to be remembered, Billy replied, as he had on other occasions, that he wanted to be remembered as one who was faithful to the gospel.

As for Billy Graham the man, his life was on public display to a whole nation and to much of the world for over half a century, in an era of highly intrusive media coverage. The fact that he emerged from such scrutiny virtually unscathed speaks volumes as to the integrity of his character.

Of all that we could mention, good or bad, it is his humility that seems to stand out. Ruth said that he ‘seemed completely unaware of how special he was’. Billy Graham seems to me to have been a sincere, humble and gifted follower and preacher of the Lord Jesus Christ, of unquestioned moral integrity, loving and lovable.

Conclusion

The evidence suggests that when Billy Graham knelt on that golf course in Florida, all those years ago, and told God he would be what God wanted him to be and go where God wanted him to go, he truly meant it.

Despite real problems with his theology and methods, and the damage done by these, especially concerning his ecumenical relations, his was an extraordinary life that God chose to use in extraordinary ways.

Dennis Hill is pastor of Kingston Evangelical Church, Hull.

References

1 I think the best treatment of Graham’s life is by William Martin, A Prophet with Honour: The Billy Graham Story, William Morrow, 1991.

2 Grant Wacker, America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation, Belknap Press, Harvard University, 2014, p.143.

3 Ibid., p.324.

4 Martin, p.583.

5 Ibid., pp. 184-85.

6 Ibid., p.232.

7 Wacker, quoting George Marsden, p.90.

8 Martin, p.222.

9 David Aikman, Billy Graham: His Life and Influence, Thomas Nelson, 2007, pp. 121-22.

10 Martin, p.218.

11 Patricia Daniels Cornwell, A Time for Remembering: The Ruth Bell Graham Story, Harper & Row, 1983, pp. 133-34.

12Martin, p.223.

13Billy Graham, Just As I Am, Harper Collins, New York, NY, 1997, p.542.

14Graham, p.853.