In Jane Austen’s novel Northanger Abbey, one of the characters, Catherine Morland, states that history ‘tells me nothing that does not either vex or weary me. The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all’!

Examination of the history books of Austen’s era would soon confirm the truth of this statement. Only in recent days has there been sustained interest in the lives of Christian women.

Earlier generations may have been slow to recognise the important — and biblically legitimate — roles women have played in the life of the church.

But we cannot avoid the fact that God has given women rich ministries down the history of the church, ministries that are fully consistent with the biblical pattern of male eldership.

Among these responsibilities is that of keeping house and raising children to God’s glory. It was such a ministry that God gave to Sarah Pearce (d.1804).

Sarah Pearce

Sarah Hopkins was a third-generation Baptist. Her father was Joshua Hopkins (d.1798), a grocer and a deacon in Alcester Baptist Church, Warwickshire, for close to thirty years. Her maternal grandfather was John Ash (1724-1779), the noteworthy pastor of the Baptist cause in Pershore, Worcestershire.

Sarah met Pearce soon after he arrived in Birmingham, and they were soon deeply in love. As he wrote to her on 24 December 1790:

‘Were I averse to writing … one of your dear Epistles could not fail of conquering the antipathy and transforming it into desire. The moment I peruse a line from my Sarah, I am inspired at the propensity which never leaves me, till I have thrown open my whole heart, and returned a copy of it to the dear being who long since compelled it to a voluntary surrender, and whose claims have never since been disputed.’

They were married on 2 February 1791. Pearce’s understanding of what should lie at the heart of their marriage finds expression in a letter written to his future wife shortly before their wedding: ‘may my dear Sarah & myself be made the means of leading each other on in the way to the heavenly kingdom & at last there meet to know what even temporary separation means no more’.

Esteem

Pearce’s love for his wife deepened with the passing of the years. Three and a half years after their marriage, he wrote to her from Plymouth: ‘O, my Sarah, had I as much proof of my love to Christ as I have of my love to you, I should prize it above rubies’.

And when Pearce was away on a preaching trip in London in 1795, he wrote to tell her that ‘every day improves not only my tenderness but my esteem for you’. On the same trip he called her ‘the dearest of women — my invaluable Sarah’.

In another letter written about the same time he informed the ‘partner of my heart’ that his letter was a ‘forerunner of her impatient husband who weary with so long an absence [longs] again to embrace his dearest friend’.

The following year, on an extensive preaching trip in Ireland, he wrote from Dublin on 24 June 1796:

‘Last evening … were my eyes delighted at the sight of a letter from my dear Sarah … I rejoice that you, as well as myself, find that “absence diminishes not affection”. For my part I compare our present correspondence to a kind of courtship, rendered sweeter than what usually bears that name by a certainty of success.’

And then towards the end of the letter he added: ‘O our dear fireside! When shall we sit down toe to toe, and tete á [sic] tete again — Not a long time I hope will elapse ’ere I re-enjoy that felicity’.

Passion for God

That Sarah felt the same towards Samuel is seen in a letter she wrote after her husband’s death to her sister Rebecca.

Rebecca had just been married to a Mr Harris and Sarah prayed that she might ‘enjoy the most uninterrupted happiness…(for indeed I can scarce form an idia [sic]…this side of Heaven of greater) equal to what I have enjoyed’.

One final word about Samuel and Sarah’s marriage needs to be said. What especially delighted Pearce about his wife was her passion for God.

As he told her in the summer of 1793, in response to a letter he had received from her: ‘I cannot convey to you an idea of the holy rapture I felt at the account you gave me of your soul prosperity’.

An evangelistic spirituality

A leading characteristic of Pearce’s spirituality, already noted in Part I, was his continual focus on the cross of Christ. ‘Christ crucified’, wrote his good friend Andrew Fuller (1754-1815), ‘was his darling theme, from first to last’.

Another prominent feature of his spirituality was a passion for the salvation of his fellow men. On a preaching trip to Wales in July 1792, for instance, he wrote to Sarah about the lovely countryside: ‘every pleasant scene which opened to us on our way (& they were very numerous) lost half its beauty because my lovely Sarah was not present to partake its pleasures with me’.

But, he added: ‘to see the Country was not the immediate object of my visiting Wales — I came to preach the gospel — to tell poor sinners of the dear Lord Jesus — to endeavour to restore the children of misery to the pious pleasures of divine enjoyment’.

This passion is strikingly revealed in four events. We will relate one in this instalment of our article, and reserve the others for Parts 3 and 4.

Preaching at Guilsborough

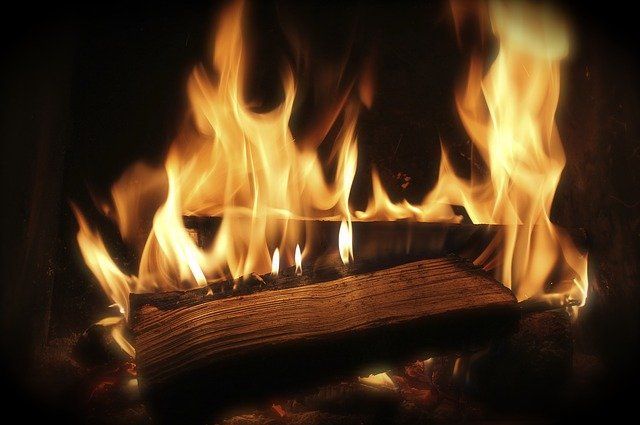

The first took place when he was asked to preach at the opening of a Baptist meeting-house in Guilsborough, Northamptonshire, in May 1794. The previous meeting-house had been burnt down at Christmas 1792 by a mob hostile to Baptists.

Pearce had spoken in the morning on Psalm 76:10 (‘Surely the wrath of man shall praise thee: the remainder of wrath shalt thou restrain’).

Later, during the midday meal, it was quite evident from the conversation that Pearce’s sermon had been warmly appreciated. It was thus no surprise when Pearce was asked if he would be willing to preach again the following morning.

‘If you will find a congregation’, Pearce responded, ‘I will find a sermon’.

It was agreed to have the sermon at 5.00am so that a number of farm labourers who wanted to hear Pearce preach could attend before their day’s work commenced.

Poor structure

After Pearce had preached the second time, and that to a congregation of more than 200, he was sitting at breakfast with a few others, including Andrew Fuller. The latter remarked how pleased he had been with the content of his friend’s sermon, but that the sermon seemed poorly structured. ‘I thought’, said Fuller, ‘you did not seem to close when you had really finished. I wondered that, contrary to what is usual with you, you seemed, as it were, to begin again at the end — how was it?’

Pearce’s response was terse: ‘It was so; but I had my reason’. ‘Well then, come, let us have it’, Fuller responded jovially. Pearce was reluctant to divulge the reason, but after a further entreaty from Fuller, consented.

Effort

He related the following, which was put into print many years later by one who was present on the occasion:

‘Well, my brother, you shall have the secret, if it must be so. Just at the moment I was about to resume my seat, thinking I had finished, the door opened, and I saw a poor man enter, of the working class; and from the sweat on his brow, and the symptoms of his fatigue, I conjectured that he had walked some miles to this early service, but that he had been unable to reach the place till the close.

‘A momentary thought glanced through my mind — here may be a man who never heard the gospel, or it may be he is one that regards it as a feast of fat things; in either case, the effort on his part demands one on mine.

‘So with the hope of doing him good, I resolved at once to forget all else, and, in despite of criticism, and the apprehension of being thought tedious, to give him a quarter of an hour.’

As Fuller and the others present at the breakfast table listened to this simple explanation, they were deeply impressed by Pearce’s evident love for souls.

Not afraid to appear as one lacking homiletical skill, especially in the eyes of his fellow pastors, Pearce’s zeal for the spiritual health of all his hearers had led him to minister as best he could to this ‘poor man’ who had arrived late.

Most of the letters cited are from one of the following three sources, all of which are housed in the Angus Library, Regent’s Park College, University of Oxford:

Samuel Pearce Mss; the Samuel Pearce Carey Collection — Pearce Family Letters; the Pearce-Carey Correspondence 1790-1828.

For permission to use these letters I am indebted to Regent’s Park College, University of Oxford.