‘For he who eats and drinks in an unworthy manner eats and drinks judgement to himself, not discerning the Lord’s body’ (1 Corinthians 11: 29)

God’s Word shows us the consequences of sin, not to depress us but that, by doing things the right way, we might avoid shipwreck. There are things to learn from the careless way the Corinthian Christians conducted themselves at the Lord’s Supper. The immediate reason for their need of self-examination before communion was that they had been abusing the Supper. So much so that, in Paul’s words, they had become ‘guilty of the body and blood of the Lord’ (11:27). This was displeasing to God, because it effectively denied the very meaning of Christ’s death and the purpose of the Supper. Instead of putting themselves in the way of God’s promised blessings, they had incurred his judgements and covered themselves with guilt. Paul tells us all this so that we will not do likewise. It is important, therefore, that we take to heart what it means to ‘discern the Lord’s body’ (11:29) and why it was that God chastised the Corinthians (11:30-32). This will help us to understand how we can rightly approach the Lord’s Table (11:33-34).

Discerning the Lord’s body

The apostle’s charge is quite startling: ‘For he who eats and drinks in an unworthy manner eats and drinks judgement to himself, not discerning the Lord’s body.’ Notice that there is a positive principle here — we must ‘discern the Lord’s body’ (11:29) — together with a warning about the consequences of ignoring the principle.

The positive principle is that we should ‘discern the Lord’s body’. The word ‘discern’ (Greek dikrino) means to separate; that is, to distinguish what is proper from what is not. In this instance, discerning means seeing the distinctness of the sacramental use of bread and wine over against their ordinary use in daily life. The Lord’s Supper is not just another meal. It is special. It is unique. It has nothing to do with food for the stomach. It has everything to do with food for the soul. It has to do with Jesus Christ, the cross, the resurrection, the gospel and the way of salvation.

The bread and wine as used in the sacrament are symbols of what Christ has done, is doing and will yet do for his people. They are visible signs of the invisible grace that flows from the once-for-all sacrifice of Christ in dying for his people. Discerning the Lord’s body means understanding, in a warm believing way, what the Lord’s Supper symbolizes, teaches and conveys. Only this can lead to a humble and reverent participation.

Eating and drinking judgement

To eat and drink in an unworthy manner, says the apostle, is to eat and drink judgement to oneself. This admonition is couched in negative terms but, as we shall see, it has a positive intent.

Perhaps the first question to be addressed is why this is stated in such strong terms. Why should God be so serious, so stern? To answer this, we must reflect on the significance of symbols. For example, think of your country’s flag. What does it signify? Is it no more than decorative bunting? If people trample on it, or burn it in the street, what do they convey by their actions? Surely they are expressing, in a symbolic way, their disenchantment with the country or the government. Their gesture depends for its effect entirely on the power of the symbol that they treat with such contempt. If they were to burn old curtains in the street, their gesture would be meaningless. But torching the flag is an act of rebellion.

God chastised the Corinthians because they were insulting Christ. The Supper encompasses a holy mystery that speaks of Christ and his redeeming work. To understand this is to discern Christ’s body. To fail to do so is to mock the Saviour. Why should God not be offended by such irreverence, and rise up in judgement? They needed to rethink what they were doing, repent of it, and return to intelligent obedience across the whole spectrum of their lives as believers.

The reality of judgement

Paul discerned that the Corinthians were experiencing God’s judgement. He was not speaking hypothetically, but explaining what was actually taking place. ‘For this reason many are weak and sick among you, and many sleep’, he declares (11:30).

Illness is, of course, a commonplace experience. In a fallen world, people catch colds and contract cancer. Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that illness is a judgement upon some particular sin. In the ordinary course of life, bad things happen to the best and worst, apparently quite indiscriminately (Ecclesiastes 9:2). Some sicknesses are even sent to glorify God (John 11:4; 2 Corinthians 12:8-10). We cannot, however, dismiss the possibility that a particular sickness, or even death, may be a divine judgement upon public sin.

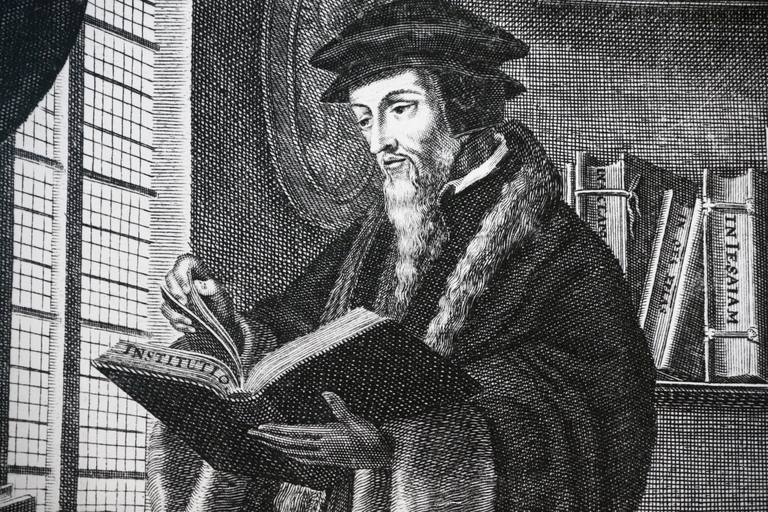

This would appear to have been the case at Corinth. The church there was seeing people sicken and even die. Paul perceives that this was more than the regular run of things. The situation was pregnant with the displeasure of God. John Calvin, observing the abuse of the Lord’s Supper in his own day, observed: ‘What a shocking mix-up there is, when no distinction is made [in admitting people to the Table], and scoundrels and people who were openly dissolute push their way in … And still we wonder what is the reason for so many wars, so many plagues, so many failures of the harvest, so many disasters and calamities, as if the cause were not in fact as plain as a pikestaff. And we certainly cannot look for an end to misfortunes, until we have removed their cause by correcting our faults.’

The purpose of judgement

It is at this point that Paul reveals the purpose of these judgements: ‘But when we are judged, we are chastened by the Lord, that we may not be condemned with the world.’ As R.C.H. Lenski observes, ‘the Lord’s judgements which he visits upon believers for the serious sins they commit are evidences of his fatherly love and not of damning wrath’. The same author notes that ‘while chastisement is painful it still proves that we are children’. We have a father who loves us enough to bring us back from self-destruction. God loves his people with an everlasting love, an eternal purpose of grace (cf. Hebrews 12:5-11).

The right attitude

How, then, should we approach the Lord’s Table? Firstly, we should come with the right attitude. ‘Therefore, my brethren,’ says Paul, ‘when you come together to eat, wait for one another.’ Here the apostle is referring to the communal meal, the ‘love feast’ or ‘Agape’, which preceded the Supper. Everyone, from the rich to the slaves, shared the food provided, the purpose being to express unity. The way they did it, however, accomplished exactly the opposite (11:17-22). Their self-seeking spilled over into the Lord’s Supper, sealing their disunity as well as demonstrating their irreverence towards Christ. So Paul directs that when they came together as a church to eat regular meals, they were to ‘wait for one another’. That is, they were to show courtesy to others, and not indulge in an unseemly rush to help themselves.

Faithful participation in the Lord’s Supper requires due preparation of the heart. Not least, it requires that the whole community of faith come together in the exercise of love for Christ and for one another. It is striking that Paul does not say ‘when you come together to sit at the Lord’s Table’. The problem was not simply that they abused the Lord’s Supper and needed to brush up on their etiquette for that particular observance. Attitude comes before etiquette. Their problem was comprehensive and spiritual. They needed repentance and renewal from the heart, with application to every aspect of their life as a congregation of professing Christian people.

The right action

‘If anyone is hungry, let him eat at home, lest you come together for judgement.’ The point here is that no one should come to either the love feast or the Lord’s Supper just because he is hungry. Neither meal was designed merely to fill the stomach. Even the church meal, the ‘love feast’, was not meant to be a charity dinner or soup-kitchen to feed the poor. The twin goals of these meals were unity and fellowship. Paul therefore instructs his readers to take whatever practical steps were needed to protect the fellowship. If they were hungry, they should eat at home before the event. Natural appetites must not be allowed to disrupt the spiritual business of the church. This can be applied to other natural appetites, such as the enjoyment of noise and chatter, entertainment, boisterous fun, and certain types of music. There may be nothing wrong with these things in their place, but the gathering of God’s people for fellowship and worship is not that place.

The right guidance

Paul’s final statement can easily be passed over as a footnote, but that would be a mistake. When he says, ‘And the rest I will set in order when I come’, he points to the abiding fact that God has provided leaders to guide his church. There are no more apostles today, but the Lord has still given government to the church. The elders are to set things in order according to the Word of God. Every believer is to discern the Lord’s body, and is responsible as an individual for his own attitude and actions in receiving the sacrament. The church, however, has a corporate responsibility, through her elders, to set things in order. The elders cannot read the hearts of their people, but they can assess the credibility of their confessions of faith and the consistency of their daily lives before allowing them to participate. It is a mark of a true church that the sacraments are faithfully administered and the people so exhorted from God’s Word that their consciences are challenged and their hearts encouraged at the prospect of joyous communion with Christ.