The fifth English kingdom to receive the faith was Wessex in 635. It was evangelised b a Roman missionary, Birinus. The kingdom of Mercia followed in 653. It seems that the ‘conversion’ of its king was a matter of convenience.

He wanted to marry the daughter of the Christian king of Northumbria. By now this was no longer Oswald – he had died in 642 and been succeeded by his brother Oswy.

Aidan had also died in 651. His successor as senior missionary to the Northumbrians was a Scot (which in those times meant an Irishman!) called Finan. He in turn was succeeded by another Irishman by the name of Colman.

Politics

During Aidan’s time the different date of Easter observed in Northumbria as compared with the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was tolerated. Under Finan, however, it began to become a matter of controversy.

By Colman’s time the dispute became heated. Some of the other matters where the Roman and British customs diverged were also becoming the focus of attention, and this was leading to political difficulties.

Oswy, along with his son Alchfrid, decided it was time to intervene. Oswy started by assuming that the British practices were correct.

Alchfrid was more inclined to side with Rome. He had been influenced by a Scot called Wilfrid who had visited Rome and Lyons, and been persuaded to change sides. He was head of a monastery in Ripon, where his predecessor had held to the British customs. As a result, what Bede (perhaps politely) calls ‘discussion’ arose within the monastery.

Synod

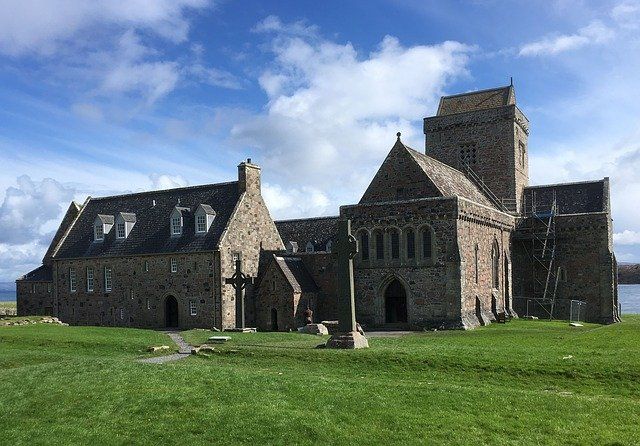

The division at Ripon led to the decision to hold a synod to settle the issue. The synod was held in 664 at a monastery in Whitby, where the Abbess Hilda and her community were based. They had moved down from Hartlepool seven years earlier.

King Oswy presided at the synod and Prince Alchfrid was also in attendance. The British party, consisting of a number of ministers trained at Iona, was led by Colman. He had the support of Hilda.

The opposing Roman party was led by Agilbert, the bishop of Winchester in Wessex. He was supported by Wilfrid and a colleague from Ripon, along with a couple of clergy, one a local man from York, and the other from Kent.

Oswy opened with a declaration of purpose. The aim was to achieve unity of practice throughout the British Isles. The synod’s task was to determine which of the rival traditions had the greater claim to be true.

New customs

Colman opened for the British contingent. He traced their customs back to the apostle John.

It was then Agilbert’s turn to speak. He requested that Wilfrid be allowed to speak on his behalf.

The reason given was that no interpreter would be needed, since Wilfrid was fluent in both the British and English languages. Agilbert was probably also aware of the advantage that Wilfrid’s shrewdness would bring the Roman cause.

Wilfrid told how he had himself observed that the customs practised in Rome were also in use in all Italy and Gaul.

He had heard reports that the same customs were followed in Africa, Asia, Egypt, Greece, and, indeed, everywhere except amongst the Scots, Picts and Britons. Wilfrid put this down to their stupidity.

Not surprisingly, Colman reacted at this point. He challenged Wilfrid to justify his accusation of stupidity. After all, the British Church could trace its customs to a great apostle.

Wilfrid then put forward a rather involved argument. He said that John followed the law in order to avoid giving needless offence to the Jews, but Peter had taught new customs consistent with the gospel.

John’s successors in Asia had recognised this change. It was now the custom of the world-wide church. Colman, Wilfrid insinuated, had ended up following neither John nor Peter, neither the law nor the gospel.

Suspect

Colman then referred to the godliness of the fathers of the British Church like Columba.

Wilfrid acknowledged their integrity, but pointed out that they had not known that different customs were practised elsewhere.

The contemporary British Church was not in that position. The British Christians would be guilty if they rejected the Roman decree.

Wilfrid then challenged Colman to say whether he preferred Columba to ‘the most blessed Prince of the apostles’. After all, the Lord had given Peter the keys of the kingdom of heaven.

At this point Oswy spoke up. He asked Colman whether Wilfrid had accurately reported the Lord’s words to Peter. Colman agreed that he had, but omitted to point out that Wilfrid’s interpretation was suspect.

Oswy then asked whether the Lord had ever said anything comparable to Columba. Colman had to admit that he had not. Oswy then asked both Colman and Wilfrid whether they were in agreement that Peter was the holder of the keys.

By now Colman was outwitted. He indicated his agreement, though he probably understood the words in a totally different way from Wilfrid.

Master of spin

Oswy then made the defining decision. Bede quotes him:

‘Then, I tell you, Peter is guardian of the gates of heaven, and I shall not contradict him. I shall obey his commands in everything to the best of my knowledge and ability; otherwise, when I come to the gates of heaven, there may be no one to open them, because he who holds the keys has turned away.’

Oswy’s superstitious understanding of admission to heaven led him to capitulate to Rome.

Sadly, Colman’s genuineness and simplicity were no match for Wilfrid’s sophistication. Wilfrid was a master of what today would be called ‘spin’.

There may be truth in the suggestion that Oswy’s decision was determined in part by the desire to foster an alliance against Mercia with the kingdoms of Wessex, Essex and Kent. Perhaps, alongside the synod, political diplomacy was taking place behind the scenes putting extra pressure on Oswy.

Oswy’s wife was baptised as a Catholic. Maybe she influenced him to act contrary to his earlier judgement. It is probably true that Oswy had no religious convictions of his own. He was fickle.

Some of the British pastors were swayed. Colman was not. Three years later he returned to Scotland. Thirty English followers accompanied him. They wanted to retain the British customs.

Churches destroyed

In Northumbria the Roman customs increasingly displaced the British way. Five years after Whitby, Bede notes with satisfaction that a Roman, Theodore, the new Archbishop of Canterbury, became ‘the first archbishop whom the entire Church of the English obeyed’.

There still remained one English kingdom almost untouched by Christianity – Sussex. A small band of Scots monks lived at Bosham near Chichester, but they had had no influence on the people around them.

But in the 680s Wilfrid left Northumbria, having fallen out with the new king, Egfrid. He moved south to Sussex and brought its people into the Catholic fold.

After Wilfrid’s departure, despite warnings from Cuthbert, Bishop of Lindisfarne, Egfrid made expeditions into Ireland and against the Picts of eastern Scotland.

He destroyed churches still following the British way. However, he paid for it with his life in a battle at Forfar.

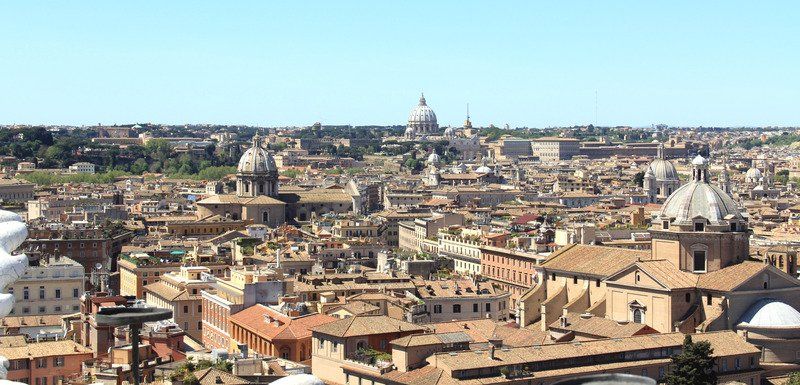

Victory for Rome

Early in the next century Adamnan, the current Abbott at Iona, visited England. He observed the Roman Catholic rites, and changed his opinions. On returning to Iona he tried, but failed, to get the monastery to go over to Catholic practice.

He was more successful, however, during a visit to Ireland. He persuaded the church there to realign itself with Rome. Iona finally fell to Rome in 716 under the influence of an Irish bishop called Egbert.

By the time Bede wrote his history in 731 he claimed that the whole of the British Isles was Roman Catholic with one exception – the Scots who occupied the south-west corner of Scotland.

This may not be wholly accurate. According to some historians, the churches of Wales continued with the British practices until the 760s, and it was not until the tenth century that the West Country finally gave in to Rome.

The victory of Rome did not mean that every inhabitant of the British Isles had been won over to the Christian religion. Pagan burial rites continued in use until into the eighth century.

Waiting for the Reformation

As late as the beginning of the nineth century many people followed pagan customs, and worshipped the pagan gods. Nevertheless, Roman Catholicism was now the religion favoured by kings and bolstered by the State.

And so things would remain for the next several hundred years. With the rest of Christendom, Britain descended into the ‘Dark Ages’. By and large, the church lost the gospel.

The light would eventually dawn again in that mighty movement of God known as the Reformation – but that’s another story.