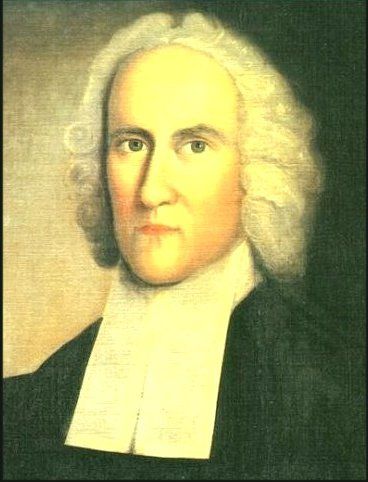

Jonathan Edwards’ writings on spirituality are of special importance, because he possessed a wonderful facility for meticulous and minute observation. This facility can be seen, for instance, in the intriguing and detailed investigation that he conducted during the early 1720s into the way that spiders made their webs.

Later in his life, this gift was exercised in the realm of pastoral ministry and theology, yielding a profound understanding of the human heart and its workings. Sereno E. Dwight (Edwards’ great-grandson and one of his early biographers) stated that Edwards’ ‘knowledge of the human heart, and its operations, has scarcely been equalled by that of any uninspired preacher’.

Dwight goes on to mention three reasons for this insightful understanding of the human heart: Edwards’ perceptive reading of the Scriptures; ‘his thorough acquaintance with his own heart’; and his grasp of philosophy. It should not surprise us that this combination of personal experience and empirical insight rooted in Scripture produced some of the most significant literature on biblical spirituality in the history of the church.

A faithful narrative

One of Edwards’ earliest works, A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God, is rich in spirituality. It is an account and analysis of the revival that took place during 1734 and 1735 in the town of Northampton where he was the pastor.

Here Edwards writes as a historian, seeking to relate what took place during the revival. Unlike his later works on revival, he did not set out to explain how the Spirit works, whether corporately in revival or personally in regeneration. Nevertheless, he does provide a pattern of sorts for the work of conversion, and thus deals with the subject from the viewpoint of Christian spirituality.

First, Edwards discusses how individuals become aware of the miserable condition in which they actually exist and ‘the danger they are in of perishing eternally’. Some are ‘brought to the borders of despair, and it looks as black as midnight to them a little before the day dawns in their souls’.

Many of them initially seek to reform their lives — ‘to walk more strictly, and confess their sins, and perform many religious duties, with a secret hope of appeasing God’s anger, and making up for the sins they have committed’. When these people ‘see unexpected pollution in their own hearts, they go about to wash their own defilement and make themselves clean’.

Entirely just

Invariably, though, such attempts at self-help fail, and they are led by the Holy Spirit to a ‘conviction of their absolute dependence on his [God’s] sovereign power and grace, and a universal necessity of a mediator’.

Coupled with this conviction is a deep sense that God would be entirely just in sending them to hell for ever. ‘Their own exceeding sinfulness, and the vileness of all their performances’ leads them to ‘a conviction of the justice of God in their condemnation’. Only then, says Edwards, are they ready to embrace the Saviour whom God has graciously provided.

This step is important in Edwards’ morphology of conversion, for it reveals the importance he placed on correct doctrine. Recognition of the sovereignty of God in salvation is, for Edwards, part and parcel of the Spirit’s work in revival.

Legal humiliation

Edwards notes that, of the sermons he preached during this period of revival, the ‘more remarkably blessed’ were those which ‘insisted on’ the doctrine of ‘God’s absolute sovereignty with regard to the salvation of sinners, and his just liberty with regard to answering the prayers, or succeeding the pains, of natural men’.

Sinners’ recognition of their spiritual plight, and the consciousness that God alone can save, are what Edwards calls ‘legal humiliation’ and ‘the drift of the Spirit of God in his legal strivings with persons’.

These discoveries do not necessarily mean that saving grace is present. But where that grace is present, it eventually manifests itself ‘in earnest longings after God and Christ: to know God, to love him, to be humble before him, to have communion with Christ in his benefits’.

At this point in the narrative Edwards does not elaborate on these ‘earnest longings’ or ‘affections’ as he later came to call them. But we shall see in a later article that they played an important role in his understanding of the Spirit’s work in revival.

The Spirit glorifies Christ

It is important to note that Edwards sees the work of the Holy Spirit as vital in personal and corporate spirituality. It is the Holy Spirit that awakens the lost to their desperate state. Unless the Spirit is poured out on a community, no growth in spirituality can take place. Even orthodox preaching is in vain, if the Spirit does not empower it.

However, it is also important to note that in this book, written to describe how the Holy Spirit works in a time of revival, Christ is mentioned far more often than the Spirit. The Holy Spirit is explicitly mentioned 35 times in the narrative, whereas Christ is mentioned more than 85 times. For Edwards, the heart of the Spirit’s work is the exaltation of the Lord Jesus.

Distinguishing marks

A second important work in Edwards’ corpus of spirituality is entitled Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God. It began as an address given on 10 September 1741 to the faculty and students of Yale College, but was published a couple of months later ‘with great enlargements’. The treatise contained an introduction and three main sections, and sought to deal with opposition to the Great Awakening.

The address was based on 1 John 4:1: ‘Beloved, believe not every spirit, but try the spirits whether they are of God: because many false prophets are gone out into the world’. In his introduction Edwards notes that the main purpose of 1 John 4 is to set forth ‘some certain rules, distinguishing and clear marks’, whereby the church might discern what is and what is not a genuine work of the Spirit.

The first section lists nine ‘negative signs’ or evidences, which cannot be used to determine whether or not the Spirit is at work in an individual’s life or corporately in revival.

In the third section (amounting to roughly half of the entire work) Edwards provides an application to the situation of his day. But it is the second section, which gives five ‘sure, distinguishing Scripture evidences and marks’ of a genuine work of the Holy Spirit, that will concern us here.

Definitive signs

The Spirit of God, Edwards points out, is a Christ-centred Spirit. He leads men and women to confess the true humanity and full deity of Christ, and focuses their thinking on Christ as ‘the only Saviour’ of sinners. He writes:

‘If the spirit that is at work among a people is plainly observed to work so as to convince them of Christ, and lead them to him — to confirm their minds in the belief of the history of Christ as he appeared in the flesh — and that he is the Son of God, and was sent of God to save sinners; that he is the only Saviour; … it is a sure sign that it is the true and right Spirit’.

Second, the Spirit opposes the ‘interests of Satan’s kingdom’ by turning sinners from sin. ‘If we see persons made sensible of the dreadful nature of sin’, Edwards writes, ‘and of the displeasure of God against it; of their own miserable condition as they are in themselves by reason of sin, and earnestly concerned for their eternal salvation, and sensible of their need of God’s pity and help, and engaged to seek it in the use of the means that God has appointed, we may certainly conclude that it is from the Spirit of God’.

The third distinctive mark of a genuine work of the Spirit of God is the inculcation of a great regard for the Scriptures as the infallible Word of God. ‘The spirit that operates in such a manner as to cause in men a greater regard to the Holy Scriptures, and establishes them more in their truth and divinity, is certainly the Spirit of God … a spirit of delusion will not incline persons to seek direction at the mouth of God’.

Devotion to the truth

A fourth indicator is that the Spirit of God is the ‘spirit of truth’ (1 John 4:6). Where people give heartfelt assent to Christian truth, the Spirit is at work.

Thus, for example, if men and women are convinced that there is ‘a great and sin-hating God’; that ‘life is short and very uncertain’; that men and women are great sinners unable to rescue themselves; and that one day they must give an account to this God; then we may conclude that the ‘spirit that works thus’ is indeed the Holy Spirit.

Finally, the Spirit of God can be recognised by the love that he produces (1 John 4:7-21). When people have ‘high and exalting thoughts’ of God and ‘his glorious perfections’; when their hearts are given an ‘admiring, delightful sense of the excellency’ of the Lord Jesus and drawn to prize him as ‘altogether lovely’ and ‘precious to the soul’; when they cease to be contentious and quarrelsome, and long for the salvation of sinners; then the Holy Spirit must indeed be the source of such love.