So far in this series we have looked at specific works by three of the early fathers, namely, Ignatius, the unknown writer to Diognetus, and Eusebius. There are three issues, present in all three of these texts, that are still relevant to the church today. We shall look more closely at the first two here, and at the third next month.

Religious pluralism

By ‘religious pluralism’ I mean the view that any set of beliefs about God and salvation is as good as any other. This is a very popular view today. The ecumenical movement teaches that all versions of ‘Christian’ belief are equally valid. The development of our multi-cultural society over the past fifty years has, for some people, even raised the question whether Christianity really is unique among the world’s many religions. The three early fathers each address this matter of religious pluralism.

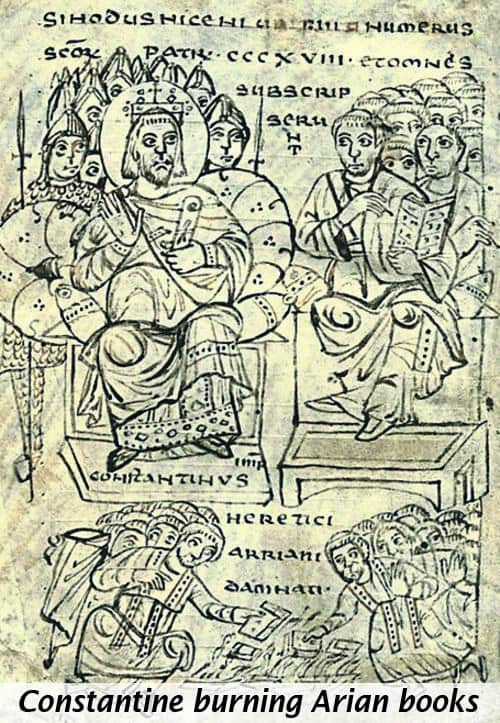

Eusebius reveals that the Emperor Constantine’s main concern was for the uniformity of the total church. To the Emperor it did not matter what the church believed, provided that the whole church believed the same thing. During the Arian controversy, Eusebius tried to help the Emperor’s cause by championing a centre party. He aimed at a compromise which would blur the differences and reconcile the opposing views about Christ, but this merely showed that he did not take seriously the doctrinal issues at stake.

The modern ecumenical movement still delights in the same kind of vagueness. The Constantinian episode reminds us that the pursuit of unity at the expense of precise definition of the truth is worthless. And yet this policy of doctrinal vagueness is the basis of the whole ‘Inter Church Process’, favoured by so many today.

Ignatius was also passionate about the unity of the church, but he emphasised that to lose the truth is too big a price to pay for unity. Heresy is divisive, and to try to reconcile right and wrong beliefs is to betray Christ.

Lost nerve?

In our undisciplined age we need to stress again how vital it is that we stand for the truth. We must insist that there are limits to the diversity which is permissible. There comes a point when certain beliefs must be ruled out as not Christian at all.

There has been a loss of evangelistic nerve on the part of the Western church in recent decades. This has happened both in our own society, where the population includes growing numbers who follow other religions, and in the context of world missions. Dialogue with other faiths has become fashionable, but such dialogue often becomes a substitute for evangelism.

The Letter to Diognetus faces this very issue. The second-century church also lived in a multi-faith society, but the writer had no hesitation in affirming what, to the worldly mind, is the ‘scandal’ of Christian exclusiveness. We should not ridicule other religions as he did, since this is counter-productive and hardly reflects the compassion of Christ, but we certainly ought to emulate his motives. He wanted to see Jews, pagans and Stoics converted to Christ, and was not ashamed to say so.

The church and the world

Secondly, these early fathers addressed the Christian attitude to, and involvement in, secular society. In the last twenty-five years, especially since the Lausanne Congress of 1974, many Evangelicals have begun to think that Christians should be far more involved in society and politics. This may seem commendable, but it is not a simple matter. There remain many Christians who regard political action with suspicion, and others who believe that relief and social work, if not irrelevant, must take second place to the priority of evangelising a world careering heedlessly towards hell.

Our three early fathers take different views on this issue of church and world. At one extreme we have Ignatius. For him the world is unquestionably in the power of the devil and in total opposition to the kingdom of God. The church within the world is a suffering community, and love of the world amounts to friendship with Satan. The return of Christ is so imminent that there is no time to bother about trying to reform society.

The Letter to Diognetus is more moderate in tone. Christians should take their place in society as good citizens, while remembering that this world is not their ultimate home. They repudiate the world’s evil practices, and endure its hostility. Their true citizenship is heavenly. Nevertheless, their earthly citizenship should be exemplary, and the well-being of the world is due to the presence and prayers of the church.

At the other extreme stands Eusebius. For him the mission of the church is to take over and ‘Christianise’ society. His theology is highly political because he has lost the authentic Christian hope of the return of Christ. All that remains is a temporal hope, which bestows an almost messianic status upon world leaders, and sees the church as part of the political establishment.

Balance

The political events of the time of Eusebius serve as a reminder that, whenever the church’s ambition has been to take over the world, the world has, in fact, taken over the church. On the other hand, an anti-worldly creed as extreme as that of Ignatius becomes bizarre when it makes martyrdom the highest goal of the Christian life.

Surely, the Bible teaches a balanced combination of the Ignatian view that the world is in the power of Satan (1 John 5:19), with the recognition that Jesus Christ is Lord over the whole of creation and that believers are to be ‘salt’ and ‘light’, bearing testimony to his saving grace (Ephesians 1:10; Matthew 5:13-16). This balance will enable us to heed the challenge of the Letter to Diognetus to be responsible citizens, in whatever way is appropriate, while recognising that our final citizenship is in heaven (Hebrews 11:13-16).

Unanswered question

Finally, I pose a question without venturing an answer. Does the current enthusiasm of many Evangelicals for political campaigning, on issues like abortion or family matters, represent responsible Christian citizenship? Or does it indicate that we are still clinging to Constantinian assumptions and have become over-involved with the affairs of this world?

The early church did not campaign against infant exposure (the ancient equivalent of abortion) or wife-swapping (equivalent to divorce and remarriage). The Letter to Diognetus merely stated that Christians do not practise these things, and left the power of example to speak for itself.