Mao Tse Tung, Chinese political leader, had been employed as a young man in the library of Peking University. There he met with the students and dreamed with them of a New China, free from imperialism, poverty and the past.

Mao sat with students at the feet of the university’s librarian, a professor of political science. It was there that Mao first imbibed Marxist theories. Those theories, with variations of his own, would one day elevate Mao from his peasant background to become god of the Chinese people.

Testify to the truth

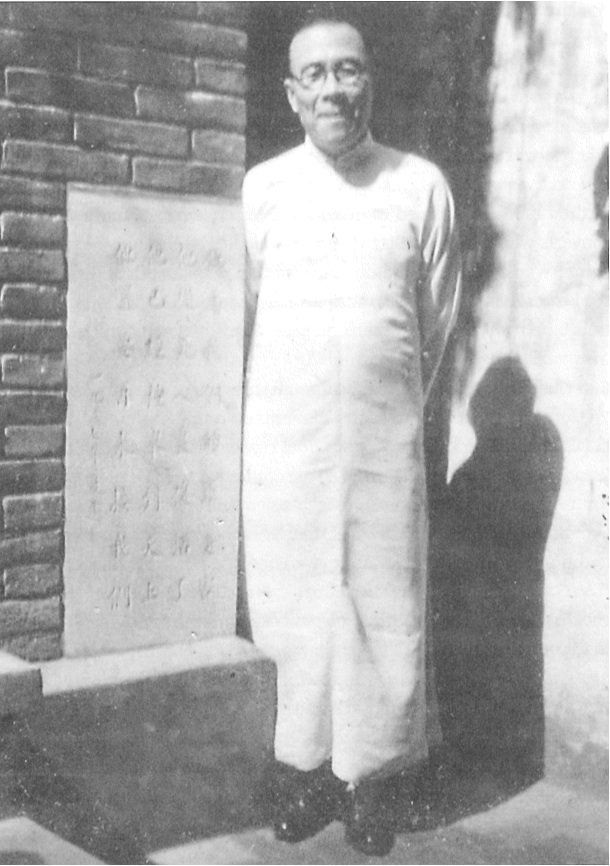

While Mao was first looking to Marxism to achieve his goal, Wang Ming Dao, just seven years Mao’s junior, had been waiting upon the one true God to realize his hopes for his country, for Wang Ming Dao’s ‘expectation was in Him’ (Psalm 62:5). This was also when Wang, to mark a new phase in his life and according to Chinese custom, was choosing the new name ‘Ming Dao’. It meant ‘revealing God’s Word’. Wang’s prayer was, ‘May God use me in this world of darkness and depravity to testify to his truth’.

Twenty-five years on, Mao, as leader of the Communist Party, was plunging his nation into civil war (1945-59); a civil war so terrible, wrote David Aiken, world renowned journalist and Chinese historian, that it would rank among ‘the greatest civil wars of all time in any country’.

As for Wang Ming Dao, now pastor of the Peking Christian Tabernacle, God was answering that earlier prayer. He had battled ‘for God’s truth as a soldier of the cross’ as he proclaimed the gospel of God’s salvation through faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. In spite of the civil war raging in the land, Wang journeyed all over China by poor public transport, past fearful sights and amidst gruesome events.

Sent by God

‘God sent me’, he said, ‘on the one hand to be a trumpet-call to the nation, and on the other hand to be a trumpet-call to the church, to expose darkness, corruption, depravity and unrighteousness and to summon men without delay to repent’.

Modernists hated his message as he dwelt often on the bodily resurrection of the Lord Jesus and pressed home the cardinal truths of the Bible. But they could not stop the ministry that was acclaimed throughout China, or silence the voice of his powerful Spiritual Food Quarterly.

‘Wang Ming Dao was a man who always sought to please God rather than man’, comments Arthur Reynolds, missionary in China and translator of many of Wang’s books. He used the two-edged sword of the Spirit, God’s Word, first of all upon himself. As Reynolds remarked, ‘he cultivated immunity against the love of popularity’, and so endeared himself to many. Fearing pride, Wang Ming Dao refused invitations to preach overseas, and gave himself to the good of China in humble dedication. His life was to change the course of the Chinese Church for ever.

Hunger for God’s Word

In the years of the civil war, known as the twilight years of Peking, the corrupt Nationalist government (the Kuomintang) still controlled that city. Food was scarce and prices soared. Communist gunfire could be heard all around. Cells were at work in every university, disseminating communist teaching. Nevertheless, amid this atmosphere of high political tension, annual Christian conferences for students were restarted.

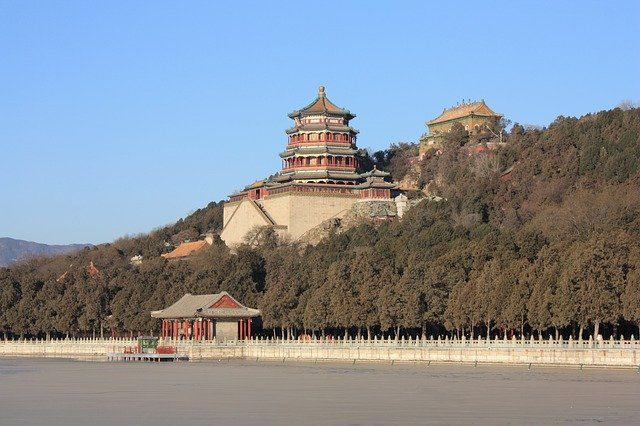

In 1947 the majestic beauty of the ancient city was as yet unscathed, and the students’ conference that year was held next to the exquisite gardens of the Summer Palace. The students arrived in truckloads and were content to sleep on straw in the stables of the conference venue. Most students were poor and hungry. But their hunger for the Word of God was greater.

Wang Ming Dao was one of the two speakers. They spoke on sin and the glory of the Lord Jesus Christ in the virgin birth, the cross, the resurrection and his second coming. Leslie Lyall, senior missionary in the China Inland Mission (now OMF), relates that they ‘witnessed and experienced a moving of the Spirit — a true reviving’. Tony Lambert, Director of Research for China Ministries and author of the forthcoming book, China’s Christian Millions, says, ‘Wang Ming Dao’s ministry had a profound effect’.

Uncompromising ministry

But Ming Dao would not count conversions. He remembered how a medical man had once examined his naturally wavy hair. ‘Hair with the appearance of yours is exactly like hair waved artificially’. He declared the waves ‘man-made’. Wang learned that even experts could be wrong. He used this incident to illustrate a point; true repentance towards God was not easy to discern. ‘Only God’, he would say, ‘knows how many have been truly saved’.

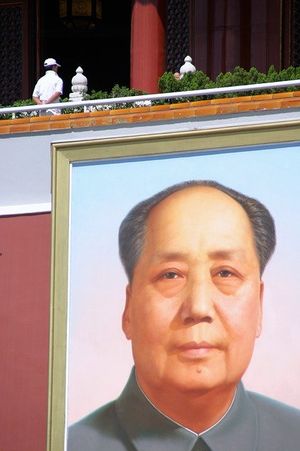

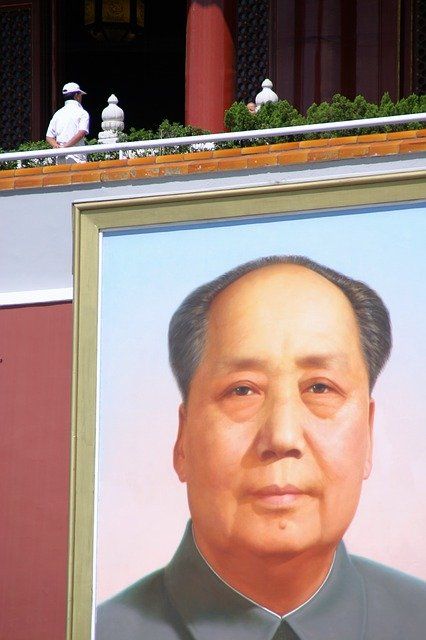

Nevertheless, on that summer’s day in 1947, the students were rejoicing as the trucks returned them to their campuses. Peking wondered, as it heard the joyful sound of praise rising to God, as the students drove past the Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tiananmen Square).

Most of the students at Peking University regularly attended the Christian Tabernacle, where they were nurtured soundly on God’s Word. According to Arthur Reynolds, Wang Ming Dao set out the characteristics of modernism so clearly, and showed so plainly how theological liberalism deviated from Scripture, that the young or ordinary believer could understand and be warned of its perils.

The students loved the man whose long face, round spectacles and uncompromising ministry could not hide his wholesome humour. To them he was ‘Uncle’.

Communist rule

Revival spread among Chinese students and in 1949 the Chinese Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship was the largest fellowship of evangelical students anywhere in the world. Wang Ming Dao was instrumental, under God, in preparing Christian leaders for the time of spiritual famine to come. They were a people who would, after persecution, ‘come forth as gold’, to preach the unadulterated gospel of salvation through the atoning work of Christ.

Meanwhile, Mao Tse Tung, with well-developed discipline and tactical skill, had greatly increased his forces. China’s northern cities had fallen to the Communists and refugees were pouring into Peking.

Many had tragic tales to tell. Soon Peking itself would fall. Food prices rose yet again. Communist troops, however, were well fed. Mao with his peasant background knew how to direct his men to live off the land. Nationalist troops, though, were based in the cities and needed money to live. To survive, they sold their sophisticated foreign weapons. So when Peking surrendered in January 1949, the Communists entered the city in their newly acquired American trucks and tanks. Before the end of the year, all China would be under Communist rule.

Belief in reform

From the top of the giant Gate of Heavenly Peace, Mao proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Many fled to Taiwan — Wang Ming Dao and Jing Wun his wife chose to stay at their post. The Communists had expected to fight longer, but suddenly, when the well-ordered soldiers from the country were seen to be victors, the Chinese people with their veneration for authority submitted to the new government. Besides, after forty years of ferocious fighting the country longed for peace. The troops were polite and helpful, different from the departing Nationalists.

But Mao’s faith was in man’s innate goodness. He believed that by persuasion or pressure and by well-laid plans, man could be reformed as he came under the Party’s control.

Wang Ming Dao, on the other hand, preached that it was only by the ‘washing of regeneration and renewing of the Holy Ghost’ that men can be permanently changed for the better, as they are brought under the benevolent rule of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Wang Ming Dao was now forty-nine years old. He stood at the highest point of his powers. But then Satan moved in with his forces