When John Bunyan asked Elizabeth to marry him he was inviting her to share not only his life but also his sufferings. A heavy burden would rest on Elizabeth’s young shoulders. First there was the care of John’s four motherless children. Mary Bunyan had died the previous year leaving behind a frail blind child of eight, also called Mary; Elizabeth, who was four; John, just two years of age and baby Thomas. But a yet darker shadow hung over John Bunyan. The death of Cromwell in 1658 spelt an end to the period of toleration enjoyed by those men and women who felt unable to conform to the strictures imposed on their worship by the Church of England. The threat of persecution was real. Already the small group of believers had been turned out of its place of worship; some members had faced crippling fines and all John’s activities were carefully scrutinized for it was widely known that he had the audacity to combine his daily labour as a tinker with preaching at many secret locations. Elizabeth’s acceptance of John Bunyan’s proposal speaks highly of the character and faith of this young woman.

Scarcely a year of married life had elapsed before Elizabeth tasted to the full that cup of suffering which her marriage entailed. Charles II had been restored to his father’s throne in May 1660 promising ‘liberty for tender consciences’. But such promises proved to be but empty words. Six months later a warrant was issued for the arrest of the honest tinker-preacher.

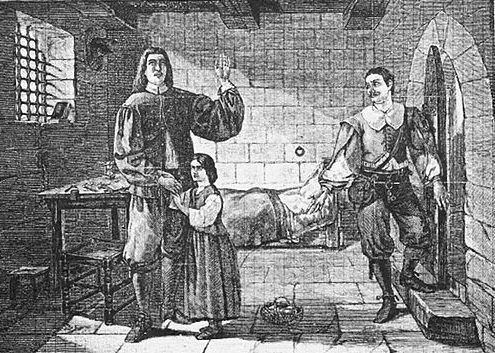

On 12 November, fully aware of the risk they were taking, some forty believers made their way quietly to an isolated farmhouse outside Bedford. Forewarned that their secret location had been discovered, John Bunyan hesitated before proceeding with the meeting. If he were arrested and thrown into prison, what would happen to Elizabeth, now expecting her first baby? And who would provide for his family, for he was their only breadwinner? Thrusting aside such anxieties as unworthy of a man of faith, Bunyan opened the meeting. Moments later an ominous rattle at the door confirmed his fears. John Bunyan was brusquely hurried off to face the local Justice of the Peace.

Determined to preach

News of her husband’s arrest soon reached Elizabeth. Many accounts circulated amongst the small groups of Non conformists of the atrocities and injustices committed against those who fell into the hands of their persecutors: torture, banishment and even execution. Shock and distress overwhelmed the young woman, bringing on her labour pains. Eight days later Elizabeth’s child was born prematurely, but soon died.

Meanwhile, days of intense cross-examination followed for Bunyan. His unwillingness to attend his local parish church was one cause of offence, but even greater was his determination to continue preaching as opportunity arose. Had he but agreed to refrain from this activity, dear to him above all other, he could have purchased his freedom. At last sentence was pronounced: he must remain in prison until the next assizes. If he would not then comply with their demands, he must either face banishment or death. Thoughts of Elizabeth and his family distressed Bunyan: ‘I was as a man pulling down his house on the head of his wife and children; yet, thought I, I must do it, I must do it.’ Only an unusual consciousness of God’s love and favour sustained him through these dark days.

Recovering from her initial trauma and sorrow, Elizabeth began to think of ways to help her husband. Her first noble endeavour was to travel to London and present a request for his release at the House of Lords — an astonishing undertaking for a seventeenth-century country girl. But their lordships excused themselves from acting on her behalf by telling Elizabeth that they could not help because such matters were for the judiciary to whom she must appeal at the next assizes.

The Bedford Midsummer Assizes were to be held in August that year and Elizabeth was determined to submit John’s case in person to Sir Matthew Hale, a judge known for his equity and compassion. Pressing through the crowds Elizabeth made her way to the Swan Inn where four judges were assembled to pass sentence on all cases accumulated since the last assizes. Suppressing her fears, she approached Sir Matthew and presented her petition. Looking kindly at the young woman, the judge promised to look into the matter, but feared there was little he could do.

Fortitude and faith

Anxious lest her case should be ignored, Elizabeth planned a yet bolder expedient. She waited by the roadside the following day for the coach bearing Judge Hale and Judge Twisdon to the Swan Inn. As it passed she took careful aim and threw her petition in at the open window. Exasperated at such audacity, Twisdon snatched up the petition and angrily declared that there could be no liberty for the tinker unless he would undertake not to preach again.

Surely if she could only plead with Judge Hale in person there might yet be hope, thought Elizabeth. So on the third day of the assizes Bunyan’s courageous wife pressed through the crowds once more and flung herself before Sir Matthew. Insisting that her husband’s conviction was unlawful, she begged again and again for clemency. ‘It is recorded, it is recorded,’ barked Judge Chester dogmatically, as if that ended all argument. ‘But it is false,’ insisted Elizabeth repeatedly. Then directing her words to Sir Matthew she confided, ‘My Lord, I have four small children that cannot help themselves of which one of them is blind, and have nothing to live upon but the charity of good people.’ ‘Alas, poor woman,’ Hale replied sympathetically, particularly when he heard of the child she had lost. But her pleas were in vain. Realizing that he had no support from other members of the bench, Sir Matthew at last advised Elizabeth to seek out a writ of error or a personal pardon from the king himself. At this, Judge Chester snapped angrily, ‘My Lord, he will preach and do what he likes.’ ‘He preaches nothing but the Word of God,’ interposed Elizabeth. ‘He preach the Word of God,’ snarled Twisdon sarcastically, lunging threateningly towards Elizabeth as if he were about to strike her. ‘His doctrine is the doctrine of the devil.’ ‘My Lord,’ responded Elizabeth courageously, ‘when the righteous Judge shall appear it will be known that his doctrine is not the doctrine of devils.’

Clearly honour and truth counted for little in such circumstances, and Elizabeth could see that nothing would be done. No longer able to restrain her tears, she made as she wept her way back through the crowd. But her grief was not for her situation nor even for the harsh treatment she had received, but, as she later told her prisoner husband, it was for the ‘sad account such poor creatures will have to give at the coming of the Lord, when they shall answer for all things done in the body’.

For twelve long years John Bunyan lay in the Bedford jail. Elizabeth struggled valiantly to bring up his family on the slender income he received from his writings and from the laces he made and sold at the prison gate. Each day blind Mary brought a jug of soup for her father; but gradually she grew frailer and her death at only seventeen years of age deepened John and Elizabeth’s sufferings. At last in 1672 John Bunyan was set free under the terms of the Declaration of Indulgence issued by Charles II. Two children of her own gladdened Elizabeth’s later years, but her fortitude and faith have earned for this young woman a well-deserved place among the heroines of the church of Jesus Christ.