Wlan of Aberdeen published Ralf Erskine’s writings under the above title, he was not thinking of the appearance of the man he admired but of the spiritual gems revealed in his fine sermons and poetry. Gentle James Hervey gave most of his books away but he kept Erskine’s Gospel sonnets on his writing desk for constant study throughout his Christian life. Though too weak to write, one of Hervey’s last dying tasks was to dictate a preface to a new edition of Erskine as he had found during his life no human works ‘more evangelical, more comfortable, or more useful’.

Ralf Erskine (1685-1752) was born in Monilaws, Northumberland, where his Scottish father Henry Erskine ministered. Ralf’s early life was full of disruption as his father refused to renounce the Solemn League and Covenant which caused his expulsion from the Church of England, and the Scottish Assembly looked down their noses at him as he ‘kept conventicles’. Thomas Boston, famous for his Human nature in its fourfold state, was one of Henry Erskine’s converts. Ralf experienced marvellous answers to prayer as a small child and penned in his exercise book, ‘Lord, put Thy fear in my Heart. Let my thoughts be holy, and let me do for Thy glory, all that I do. Bless me in my lawful work. Give a good judgement and memory-a firm belief in Jesus Christ, and an assured token of Thy love.’ With this background, Ralf made excellent progress at school and entered Edinburgh University at the age of fifteen to study divinity. During his holidays, Ralf stayed with his brother Ebenezer who ministered at Portmoak though unconverted. In old age, the more famous Ebenezer spoke of the two advantages his younger brother had over him. He came to know the Lord earlier and went to be with the Lord earlier. After qualifying, Ralf worked as a private chaplain to his relative Colonel John Erskine. The colonel wrote to Ralf saying, ‘I beg earnestly that the Lord may bless your good designs to my children; and am fully persuaded that the right impressions that children get of God and the ways of God, when they are young, is a great help to them in life.’

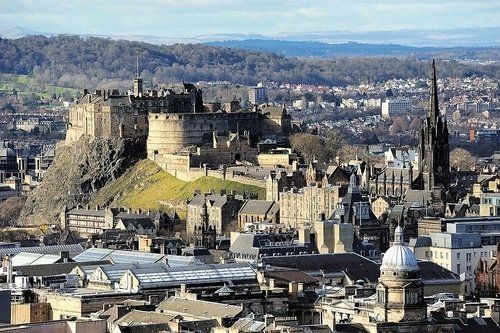

By 1709 Ralf was old enough to be licensed as a preacher but he felt unworthy of the task. The colony did all in his power to persuade him and after Ebenezer had secretly heard Ralf practice preaching, he gave his brother every encouragement to enter the ministry. The Dunferrnline Presbytery put Erskine ‘on trial’ and became convinced that he was a man sent by God to preach the gospel. It was in Dunferrnline that Charles I of England was born and it was in this town that Ralf pastored his first flock.

Once Erskine was called to the ministry, he was filled with grave doubts as to his Christian witness and calling and scoured the works of godly men to find comfort. On reading Boston on the Covenant, he was able to plead the promises of God and regain peace of heart. He now went through a period of great energy. So intent was he on studying the Word, praying and preaching that he ignored sleep and could be still found at his desk long after midnight. His motto became, ‘In the Lord have I righteousness and strength.’ Erskine’s view of himself, as shown by his diary at this time, is highly instructive. He writes, ‘This morning, after reading, I went to prayer under a sense of my nothingness and naughtiness, vileness and corruption and acknowledged myself “a beast before God”.’ He could nevertheless add, ‘Yet looking to God as an infinite, eternal and unchangeable Spirit, who from everlasting to everlasting is God, and always the same, and who manifests Himself in Christ … I think He allowed me some communion with Him in a way of believing, and I was made to cry with tears, “Lord I believe, help Thou mine unbelief.” I was led, in some suitable manner, under a view of my nothingness, and of God’s all sufficiency, to renounce all confidence in the flesh, and to betake myself solely to the name of the Lord, and there to rest and repose myself.’

Erskine was united in marriage to Margaret Dewer, a gentleman’s daughter, in 1714. Margaret was noted for her kindness and care and served at Ralf’s side for sixteen years, bearing him ten children, five of whom died in infancy. Telling a friend how Margaret died, Erskine said, ‘Her last words expressed the deepest humiliation, and the greatest submission to the sovereign will of God, that words could manifest, and thereafter, she shut up all that-“O death, where is thy sting! O grave, where is thy victory! Thanks be to God who giveth us the victory through Jesus Christ our Lord!”-which she repeated two or three times over. And yet, even at this time, I knew not that they were her dying words, till instantly I perceived the evident symptoms of death; in view whereof I was plunged, as it were, into a sea of confusion, when she, in less than an hour after, in a most soft and easy manner, departed this life.’

Some two years later Erskine was married to Margaret Simson of Edinburgh and in June 1732 we find him writing, ‘I was made to bless the Lord for his goodness in providing me a wife whose temper was so pleasant and peaceable.’ Erskine experienced great blessing as he and his wife taught their children of the mercies of God in Christ, but their faith was tried many a time as one child after another died. Erskine’s ministry was so blessed that revival broke out and the worshippers filled the church and church yard. After the service prayer and thanksgiving went on in small groups sometimes all night long. One seeker arose at two in the morning to pray in secret and found the whole town on its knees so that the entire countryside hummed like a gigantic hive of bees as hundreds of penitent sinners poured out their petitions to God under the dome of heaven. The seeker writes marvelling at the fact that he could hardly find a place to pray though it was raining steadily.

Professions were so numerous and the Lord’s Table so crowded that Erskine and his brother pastors began to soundly catechise the people to remove the chaff from the wheat, only to find the former hardly present. Erskine’s sermons are extant in which he portrayed hell so that his hearers felt they were already there, and then he portrayed heaven’s open doors in Christ and admonished his hearers to flee from the wrath to come. This method produced genuine conversions.

All was not plain sailing for Erskine. The error prevailed that all men receive a common grace to be improved on. This could develop into saving grace which. in turn could he neglected and rendered ineffectual. This view was coupled with neonomianism, the teaching that faith became savingly effective through keeping the New Law of ‘sincere obedience’. When Edward Fisher’s Marrow of Modern Divinity was republished, men such as Hog, Boston, Wilson and the Erskines saw in it a refutation of these errors. The Scottish Assembly regarded the book as a plea for antinomianism and branded those who supported its teaching, popularly called the Marrow Men, as heretics. Then the assembly legalized the appointment of ministers via patrons rather than the vote of church members and as the Marrow Men protested against this move they were gently but firmly thrust out of the denomination. Both sides accused the other of acting contrary to the church confessions. The assembly genuinely thought the Marrow Men were making justification the goal of faith rather than Christ and showing disrespect to those in authority. They, in turn, felt that the assembly mistook anti-Baxterism and anti neonomianism for antinomianism and showed too much respect for ‘persons of quality’. After much inner conflict, Ralf Erskine believed he ought to identify himself with the Secession and entered into his diary on Wednesday 16 February 1737, ‘I gave in an adherence to the Secession, explaining what I meant by it. May the Lord pity and lead.’ The great majority of Erskine’s congregation wasted no time in leaving the Established Church with Erskine and erecting a new place of worship.

The next unhappy chapter in the Erskines’ life was the quarrel with Whitefield. Most likely because of the difficulties the Erskines had with the assembly, they began to develop most rigid views of church government so that when Whitefield came to preach around 1742, the Seceders refused to support him because of his supposed laxity in matters of church order. Whitefield’s biographer Middleton comment: ‘Most certainly, he did not care for all the outward church government in the world, if men were not brought really to the knowledge of God and themselves. Prelacy and presbytery were indeed matters of indifference to a man, who wished “the whole world to be his diocese” and that men of all denominations might be brought to a real acquaintance with Jesus Christ.’ Sadly however in campaigning for their own right to dissent, the Erskines refused Episcopalian Dissenters any right to that same freedom.

Such times of controversy were seldom as most of Ralf Erskine’s life was taken up with winning souls and training young ministers. His literary works were so treasured that as late as 1879 they were still the best-selling religious books in London. Typical of Erskine’s exposition is that of Luke 14:23 on the compelling duty of ministers. ‘Their work is not only driving work, while they preach the law as the schoolmaster to lead to Christ; but it is also drawing work, while they preach the Gospel of Christ, who was lifted up to draw men to Him by His love and grace. Their work is winning work, seeking to win souls to Christ, compelling them to come in; and their work is filling work, that their Master’s house may be filled; and that every corner, every seat, every chamber, every storey of His house may be filled. As long as the Gospel is preached, His house is filling; and as long as there is room in His house, there is work for the minister; his work is never over, so long as His Master’s house is empty; compel them to come in, that my house may be filled.’

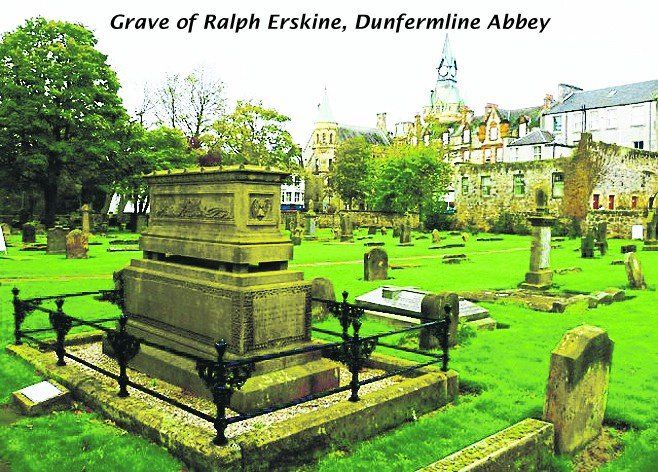

In the autumn of 1752 Erskine’s wife begged him to slow down his pace of work and spend more time with the family. He promised to do so and in October received a strong conviction from God that his work was at an end and he could prepare himself to depart in peace. That departure came very quickly. Death struck Erskine in November of the same year whilst carrying out his duties though suffering from a heavy fever. His deathbed message was difficult to understand as it was spoken in great weakness. Those around him caught the words, ‘I will be for ever a debtor to free grace.’ As God called him home, Erskine’s last utterance rang out crystal clear for all to hear, ‘Victory, victory, victory!’