Last month we saw how God prepared his people for revival. We take up the narrative at the General Meeting for the prayer societies in the parish in January 1742. This left the parish with a heightened sense that God was about to do a work amongst them. On the Sabbath, 31 January, McCulloch preached on 2 Corinthians 1:3: ‘the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of all mercies, and the God of all comfort’. He told his congregation, ‘He shall come unto us as the rain’. Then two men organised a petition for a weekly ‘lecture’ or Scripture exposition. This was started on Thursday 4 February, and evidenced a great thirst for the Word of God.

A great stir

Sabbath, 14 February, was ‘the spark’. The church was full and many were standing. McCulloch preached on John 3:3 and the necessity of the new birth, ‘on which he had been insisting a long time before’.

A young woman called Catherine Jackson became distressed and, together with her two sisters, was taken to the manse for counsel by a visiting preacher and several elders. She came to saving faith and exhorted those around her, ‘My beloved is … the chief among ten thousand, yea he is altogether lovely. O sirs, will ye come to Christ… If ye cannot cry to him, O long after him’. An observer commented: ‘At this there was a great stir … that might be heard at a considerable distance’.

Thereafter there were daily gatherings of seekers, weeping and crying for help. Every day a sermon was preached. The manse was besieged by seekers. Elders and ministers from other parishes were pressed into service. Anyone who could give out a psalm, or read a portion of Scripture, would do so to small groups of awakened men and women.

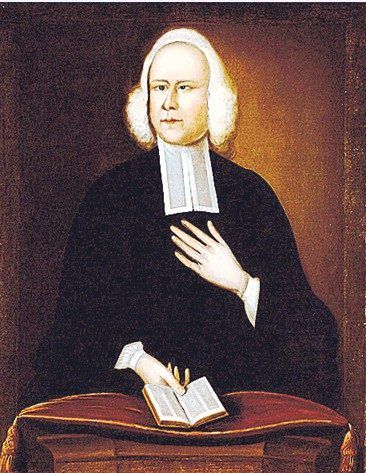

Whitefield at Cambuslang

By March 1742 news of these events had reached Whitefield who was then in England. On 28 April McCulloch wrote to Whitefield asking him to come to Cambuslang. In July Whitefield arrived in Scotland for his second visit and came to Cambuslang. There followed the first of two amazing communion seasons in the parish that marked the high point of the Cambuslang Awakening.

Communion seasons have often been the occasion for revival. The awakening at Kirk O’Shotts in 1630 was a notable example. During the Great Awakenings on the American frontier, great crowds gathered at the communion seasons. The subject matter of sacramental preaching set forth the central doctrines of man’s ruin and divine redemption. Strict control over who was admitted made both the communicants and observers examine their hearts, that they were savingly related to God.

On Saturday 10 July Whitefield preached to a gathering of more than 20,000 people. He was to preach seventeen sermons in Cambuslang. The services were held out of doors at a natural amphitheatre near the meeting-house. About 1700 communed. McCulloch estimated that ‘above 500 souls … have been savingly brought home to God’.

In the evening, Whitefield preached from Isaiah 54:5: ‘Thy Maker is thy Husband; the Lord of Hosts is His name’. He spoke of salvation as a marriage-bond and pleaded for his hearers to ‘take Christ’. One, Daniel McLarty, ‘almost cried out for joy at the sweet offers of Christ as a husband to my soul’. Another, Margaret Carson, considered the alternative, ‘to have the devil for your husband and to sleep all the night in the devil’s arms’. Prayer and praise continued in small groups through the night. People could hardly bring themselves to leave for home.

The revival spreads

The Kirk session decided to hold a second communion season on 15 August.

James Robe of Kilsyth wrote: ‘It hath not been known in Scotland that the Lord’s Supper hath been given twice in a summer in any congregation before this revival’. The numbers attending reached 30,000 with people coming from a wide area. More than twenty-four ministers were in attendance and 3000 came forward to the Lord’s Table. Whitefield wrote: ‘Such a Passover has not been heard of’. McCulloch observed: ‘Our Saviour loves to let us see yet greater things’.

The awakening that started in Cambuslang spread to nearby Kilsyth, and from there to many parts of Scotland. Space does not permit us to follow these rippling effects. Let us learn what we can from the great work of God in Cambuslang about true revival.

Difference of degree

Iain Murray notes that ‘what happens in revivals is not to be seen as something miraculously different from the regular experience of the Church. The difference lies in degree, not in kind. In an “outpouring of the Spirit” spiritual influence is more widespread, convictions are deeper, and feelings are more intense, but this is only a heightening of normal Christianity’. Much that is typical of this heightening and deepening took place at Cambuslang. Students of revival in other places and at other times will discover many common experiences and incidents.

There is, however, one feature that gave this awakening its distinctive character. It is the fact that ‘a rather colourless parish minister’ (as McCulloch had been called) gave such emphasis to the doctrines of the new birth in his regular parish ministrations. The ministry of Whitefield came after the awakening had commenced. The instrument that the Holy Spirit was pleased to use was McCulloch himself and his constant teaching about the new birth. This doctrine is the prism through which we ought to view the Cambuslang work; and the Cambuslang Awakening is a prism through which we can gain a clearer insight into the nature of the new birth.

The new birth

The leading features of the doctrine of the new birth can be summarised as follows.

Firstly, the new birth is a work of God in which the sinner is absolutely helpless. This is the most significant feature of the biblical doctrine. This is what Nicodemus found so hard to understand. That is why Jesus said, ‘Marvel not that I say unto thee, ye must be born again’. These words do not imply a command or a duty, but convey a shocking fact that leads the sinner to despair. Spiritually speaking, Nicodemus was a dead man, who could not make himself alive. Self-reformation is like rearranging the furniture in a burning house. The new birth is an essential work that only God can do – from above.

Helplessness was a marked feature of those who were awakened during the Cambuslang Awakening. They grieved over their sin to the point of agony, yet nothing they did or said could gain them relief, or provide ‘an outgate from their distress’. Willison records, ‘I found several in great darkness and distress about their souls, and with many tears bewailing their sins and original corruptions; and especially the sin of unbelief and slighting of a precious Christ; some of whom had been in this state for several weeks past’.

McKnight records that, ‘On directing them to the words of Paul, as addressed to the Philippian jailer … their answer was, “Lord, help me to believe; gladly would I believe, but I cannot”‘. Simple human action did not bring relief. The ‘outgate’ was the new birth, which came only as the Spirit of God worked ‘from above’.

Visible change

Secondly, the new birth is a work of God in which a deep transformation is wrought in the sinner. This transformation takes place at first within the soul, then in the behaviour of the newborn child of God. At first the change is secret, spiritual and invisible. Then it is made visible by a new way of life. Our Lord used the illustration of the wind. We cannot see the wind or where it comes from, but we can see its effects. The effects in Cambuslang were clearly visible.

One witness observed ‘that secure sinners have been roused with a witness to care for the state of their souls; that those who were ignorant speak skilfully concerning religious matters; and that even the graceless increase in knowledge; that swearers stop their oaths and speak reverently of God; that vain persons, who minded no religion, but frequented taverns and frolics, passing their time in filthiness, foolish talking and jesting or singing paltry songs, do now frequent Christian societies for prayer, seek Christian conversation, talk of what concerns the soul, and express their mirth in psalms, hymns and spiritual songs; that they who were too sprightly to be devout, and who esteemed it an unmanly thing to shed tears for the state of their souls, have mourned as for an only son; and that persons who came to mock at the lamentations of others, have been convinced, and by free grace brought over to such ways as they formerly despised’.

McKnight describes how they showed the genuineness of their work ‘in their charity and love for one another, and for all who are Christ’s; in their affectionate concern for such as fall under distress and anguish of Spirit on account of sin; and in their endeavours to relieve them, whether by suitable exhortations, or by comforting with the consolations wherewith they had themselves been comforted’.

A work of God

Thirdly, the new birth is a work of God directly upon the soul. This takes us to the nature of the new birth. It is a transforming work of God’s Spirit upon a sinner’s soul.

It is immediate, in the sense that no mediating influence is used. It is a mystery, because it is not subject to physical laws or empirical enquiry. As described in chapter 10:3 of the Westminster Confession of Faith, the Holy Spirit ‘worketh when, and where, and how he pleaseth’.

For this very reason there was no fixed pattern to the regeneration of those who came to Christ during the Cambuslang Awakening. This made McCulloch wary about estimating the number of converts. Some were born as they listened to the preaching of Scripture; some long afterwards, as they walked home or sat in their homes; some in the charged atmosphere of the manse; others in more tranquil surroundings. God was not limited to certain means or places, for the new birth is a direct work of grace.

Preaching

Fourthly, the new birth is a work of God ordinarily associated with the preaching of the Word of God. This does not contradict what has just gone before. The sovereign Spirit of God is not constrained, except by his own wisdom. In the wisdom of God he chooses to link his work to the preaching of his Word. Hence James 1:18 declares, ‘of his own will he begat us with the word of truth’.

The preaching of Scripture was a prominent feature of the Cambuslang Awakening. From February onwards a daily sermon was preached. The substance of this preaching was thoroughly scriptural. ‘The sum of all these facts is that this work has been begun and carried on under the influence of the great and substantial doctrines of Christianity, pressing jointly the necessity of repentance towards God, of faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, and of holiness in all manner of conversation’.

Willison spoke of the converts that ‘their conversation was solid, their experience scriptural, and the comfort or relief they had got still came to them through some promise or word of Scripture cast into their minds’. Catherine Jackson testified that when McCulloch preached from Psalm 95:7-8, ‘that sermon proved the voice of Christ to my soul’.

Drawn to prayer

Fifthly, the new birth is a work of God that draws men and women to prayer. This is a constant feature of the testimonies of the Cambuslang Awakening, and one of the visible fruits of the new birth. In particular the converts prayed for the awakening and conversion of others.

This is also the logical consequence of the doctrine of the new birth. Since regeneration is a work of the Spirit of God upon the soul, and since his work is sovereign and immediate, to whom do we turn when we seek the regeneration of others? Why, to the one who can make sinners live!

The account of the revival which McCulloch endorsed notes that among its ‘good fruits’ was ‘the setting up of new meetings for prayer, both of young and old, partly within the parish, where 12 such meetings are now begun, and partly elsewhere among the awakened’. Willison also mentions ‘secret prayer’. Hamilton records that ‘when speaking of prayer [the converts] have told me how much they had formerly neglected that duty, and how coldly and lifelessly it had been performed. But now they had much sweetness in it’.

True Christianity

The testimonies of many who were born again during the work of God at Cambuslang describe how they had previously lived upright and law-abiding lives. They were regular in attending the ordinances of the church; conducting family worship; private prayer and Bible reading. Yet these things were done coldly, as a duty. Sound regeneration changed all that. The beginnings of their awakening was to discover what it is to be born again and that true Christianity is the enjoyment of a heavenly life. May God awaken, in our day, a lively knowledge of this often named but poorly understood doctrine – ‘Ye must be born again’.