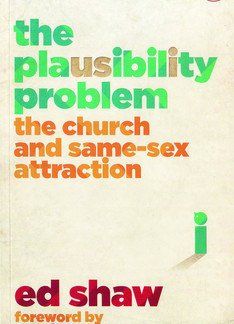

This is a book which pastors and youth leaders should read. It is written by an Anglican pastor who experiences same-sex attraction and who is quite frank about his struggles. Contemporary culture now demands that we face the issue of same-sex attraction fairly and squarely, and with wisdom and seriousness.

The main thrust of the book is to spell out what Shaw calls the ‘missteps’ taken by the church. These missteps hinder our understanding and witness, and make the biblical position seem implausible, particularly to today’s young people.

The first misstep is: your identity is your sexuality. At the end of the chapter he has an application question (as he does with the other missteps): ‘How can we all ensure our identities are defined by God’s Word, and not by the world around us?’ (p.43).

The other missteps are — a family is mum, dad and 2.4 children; if you’re born gay, it can’t be wrong to be gay; if it makes you happy, it must be right; sex is where true intimacy is found; men and women are equal and interchangeable; godliness is heterosexuality; celibacy is bad for you; and, finally, suffering is to be avoided.

You may not agree with him at every point, but all these are well worth thinking through in the light of Scripture. The last two chapters are particularly apposite for churches today.

There are two appendices. The first is, ‘The plausibility of the traditional interpretation of Scripture’. This is helpful, as he views the traditional interpretation in the light of the whole biblical story, under the headings of creation, rebellion, redemption and perfection.

The last section is very moving: ‘In the new creation, the whole church will be married to Jesus (Revelation 21:2). There will be no single people in heaven — no lonely Valentine’s Days, but instead one great eternal relationship of love, that we will all be bound up in and celebrating together forever’ (p.152).

The second appendix, ‘The implausibility of the new interpretations of Scripture’, comments briefly on four recent books which try to make a case for the acceptance of same-sex relations. Interestingly enough, it is a quotation from gay, atheist journalist Matthew Parris which answers these attempts: ‘You cannot pick and choose from revealed truth!’ (p.164).

Paul E. Brown

Halton, Lancaster

2 star review

This book comes with a foreword by Vaughan Roberts and 14 other commendations at the front. The breadth of Christian leaders which celebrate this publication include Dan Strange of Oak Hill Theological College; Terry Virgo, the founder of New Frontiers (Virgo claims to be an apostle!); four female ‘church leaders’; and the Bishop of Winchester.

Ed Shaw is an Anglican minister currently working with a new church plant called Emmanuel City Centre in Bristol. He is very open in this book, in that he explains that he is same-sex attracted to ‘beautiful men’ (p.31).

He seeks to handle the subject pastorally and from an evangelical perspective. This is a highly sensitive subject and one which needs handling with biblical thoroughness.

The opening chapter, called ‘The plausibility problem’, paints two fictional scenarios of two separate, same-sex attracted (SSA) individuals called Peter and Jane. Both of them end up embracing a liberal Christian position and living in same-sex relationships. Shaw explores how we can prevent professing SSA Christians from leaving the evangelical church.

He contends that just citing proof-texts on homosexuality into such situations is an insufficient response and an approach that lacks credibility today. He asserts that the evangelical church needs a more robust approach and he seeks to offer a way forward. Part of this is to suggest celibacy as a vibrant Christian lifestyle, one that can plausibly be without crippling frustration.

He approaches this ‘plausibility problem’ by offering nine chapters, to handle what he perceives as ‘missteps’ by the church in caring for SSA professing Christians.

The author works hard to create ‘space’ in the contemporary evangelical church for SSA Christians and, indeed, chapter 8 on ‘Celibacy’ was one of the best chapters. However, this books offers insufficient biblical exegesis and careful thought beyond the author’s own experience. It is a tenuous foundation when we mainly present broad-based solutions for what is a complex and sinful world, and this is what this book does in many ways.

The author left me with such unanswered questions as, ‘Why is the book light on answering key questions exegetically?’ ‘Why does Shaw cite female ministers and Roman Catholic writers to support his arguments?’ (pp. 24-25, 74, 88, 92, 114); ‘Why are the words lust and sin avoided in describing SSA temptations?’; ‘Is it legitimate for a Christian minister in office to be open as a SSA man and still meet the biblical qualifications of eldership?’

The primary value of this book for the evangelical church is perhaps a stimulus and much needed catalyst for the church, in the coming years, to think through their care of SSA people — that is, to find a spiritually healthy way that is intentional, diligent and biblical.

However, considering the breadth of endorsements and authors cited in this book, we also need to revisit the question, ‘What is an evangelical?’

Kevin Bidwell

Sheffield