Part 1 is here.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl harbour and the entry of the United States into the war the situation became rapidly more difficult for all the children and teachers at the Chefoo School.

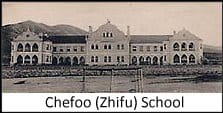

Chefoo School

The fighting in the local area between the Japanese and the Chinese had intensified. A letter had been sent to all the parents of the children at the school saying that the school would remain open for the time being. This was mainly because any other option seemed even more dangerous than staying where they were.

The weeks that followed in 1942 can be summed up in these words that David wrote:

‘Bayonet practice with blood-curdling shouts of ‘Yaa!’ formed part of our daily entertainment. We grew accustomed to the sight of soldiers straggling in, bleeding and wounded from battles in the hills. Although we were sheltered from seeing the sufferings of the local Chinese people, we heard about atrocities and sometimes heard and saw the results of beatings. The current situation… was greeted with solemn faces and a good deal of prayer. But there was no hint of panic. Never do I remember a note of alarm, fear or confusion in it all. It was simply something that happened and over which God had control’.

In the April of that year an evangelistic mission was held on the beach. Here is David’s account:

‘I enjoyed the choruses we sang during the mission, one of which spoke to my heart of what Jesus had done for me. In simple, childlike faith I sang it and meant it as I chose the way of Jesus for my life:

All the way to Calvary

he went for me, he went for me.

All the way to Calvary

he went for me,

and that’s the way for me.’

Later that year the entire school was moved to the American Presbyterian Mission at Temple Hill, about three miles away. This however proved to be only a staging post and soon they were ordered to make another longer journey.

David wrote, ‘The teachers commanded each of us to take our bedside potties with us… my personal potty kept me company until the war was over.’

While it was very sensible of the Chefoo staff to insist, it was mortifying to the children to have to carry these ‘undisguisable burdens’!

On 7 September, 1943 they set off by boat. ‘The journey took two nights and two days. The boat was desperately overcrowded, and the 200 children and teachers were assigned to the hold. The hatches were battened down at night and no one was allowed on deck. Two long, wooden shelves ran the length of the hold and the children lay top and tail like sardines. There were no toilet facilities! However, missionary foresight had anticipated this… many of the children were sick, and the nights were very long.’ Back on land they were all taken to the train station for a seven hour train journey. Then they were put on open trucks or ramshackle buses. ‘Turning east, we passed a few slum-like villages… after a mile or two high walls and fortified towers came into view… peering ahead as the dust settled, we saw Japanese sentries standing guard with fixed bayonets. Behind were high grey walls and two big wooden gates with an inscription in Chinese, ‘The Courtyard of the Happy Way’. We had reached Weihsien Concentration Camp.’

‘One of the first arrivals had described Weihsien as follows: “Bare walls, bare floors, dim electric lights, no running water, primitive latrines, open cesspools, a crude bakery, two houses with showers, three huge public kitchens, a desecrated church and a dismantled hospital, a few sheds for shops, rows of cell-like rooms, and three high dormitories for persons who are single.” It was to this scene of destruction and despair that we now came in September of 1943’.

With the Chefoo arrivals the number held in Weihsien rose to over 1,400, all living in an area of about 150 yards by 200. The number of children there was now about 500. The Chefoo group numbered 65 adults and 141 children, numbers of whom, like David, would still have been under 10 years old.

‘Nine of us boys were in a room about 12ft by 16ft. By night we unrolled our little mattresses and bedding bundles out from the wall, five down one side and four down the other. At the far end we had a bench on which we placed our wash bowls. In the middle were our cabin trunks, which served as desks, chairs, tables, playing equipment, and sometimes beds. This one room was our bedroom, classroom, living room, dining room, and playroom.’

‘Every able-bodied person was given regular work to do. In the kitchen most people worked a twelve-hour shift and then had two days off. Many of the older boys took turns at pumping water up into the water tower for the camp supply. We younger children did things such as transporting water from one side of the camp to the other and carrying the washing, which our teachers had tried to scrub clean, often without soap or brushes. We also sifted through ash heaps to try and find pieces of coke or unburned coal, and gathered sticks and anything else that would burn, to try to keep warm through the winter. Undetected by the teachers or Japanese soldiers, we sometimes sneaked into the Japanese part of the compound and climbed the tall trees looking for dead twigs or branches.’

‘Food and freedom were probably the major topics of conversation. The camp was organised into three kitchens, staffed by internees. Hands that were totally unaccustomed to the culinary arts were soon turning out fancy-named items which appeared on the daily menu board. These mysterious products completely belied their humble origin from turnips, eggplant and cabbage with occasional squid, fish or what could aptly be described as “no-name” meat. Actually, it had a name – it was either horse or mule. Morning, noon and night we lined up in long queues for our portion of food and then sat down at rough-hewn tables and benches. Servers had to try and be scrupulously fair, or there were complaints.’

A typical camp menu would be:

Breakfast

- two slices of bread (often hard and flat if the yeast supply was low)

- millet or sorghum porridge (with sugar on very rare occasions)

Lunch

- hash or stew including mushy eggplant, popularly called SOS (Same Old Stew),

- occasionally dessert

Supper

- usually soup, which was often a watered down version of SOS…

‘Second helpings were very rare. When one five-year old discovered that she was allowed a second drink of water at playtime, she shouted excitedly to the others, “Hey, everybody, seconds on water!”’

‘Sanitation was appalling: all agreed that the camp’s Health Committee had one of the hardest tasks. The sewage system consisted of open cesspools, one of which was only yards from the side windows of our room. Gangs of Chinese coolies, with buckets hanging on each end of a pole across their shoulders, came in each day to fill up and splish-splash their way up to the gate and out into their little fields. The fetid stench floated in the kitchen-dining hall area where we were eating, or on summer nights it hung low over the camp in sultry, pungent clouds. One boy had the misfortune to fall head first into one of the cesspools. Happily his brother’s frantic yells meant his sufferings were fairly short-lived. Help reached him after his fourth dunking, and to the great relief of all, “Cesspool Kelly”, as he came to be known, was pulled out and revived.’

‘The noisiest night-time entertainment by far came from the rats… To try and cut down the menace of rats and flies, rat-catching and fly-catching competitions were organized.’

One syndicate of one adult and two boys won the prize for catching 68 rats. David himself managed to catch 66 flies during one Sunday School lesson! Catching and killing bed-bugs was another necessary task, and David was once stung by a scorpion which he had not managed to rid from his bed.

In David Michell’s account one section is entitled ‘Of all the world’s great heroes’ and it starts like this: ‘Weihsien was a place of heroes… A situation like Weihsien is fertile soil for producing people of exceptional character. In our eyes, for instance, our teachers were heroes in the way they absorbed the hardships and fears themselves and tried to make life as normal as possible for us.’

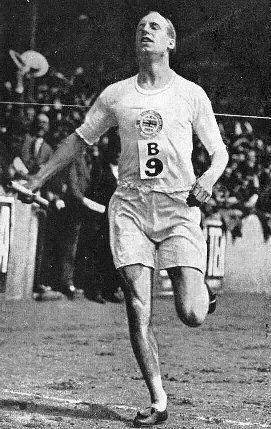

But there was one man in Weihsien who stood out above them all and that man was Eric Liddell. Born in China of Scottish missionary parents he became an outstanding athlete in Scotland where the family had returned. He famously refused to run in the 100 metres in the 1924 Olympic Games, though he was favourite to win, because he wouldn’t run on a Sunday. He entered the 400 metres instead and won in a new world record time. Later he returned to China as a missionary, marrying a Canadian missionary ten years his junior. He saw his pregnant wife, with their two children, safely on their way back home intending to follow them shortly. But he was too late and he was also incarcerated in Weihsien.

Eric lived in the room immediately above that of David and his schoolmates. ‘He was an outstanding example by his kindness and self-sacrifice. He taught science to the older students, even drawing all the apparatus for chemistry experiments so that the Oxford exams could be taken. He put up a shelf – a valuable item of furniture even if it was only a piece of wood – for a white Russian prostitute in the camp. She said of Eric that he was the only man who ever did anything for her without asking for favours in return. Often we would see him carrying a heavy load for one of the older people or walking with a young person for whom Weihsien imprisonment had brought life to a dead stop. He helped to answer questions and turn the questioning to faith in God and hope that freedom would indeed come someday…’

‘As chairman of the recreational committee, he helped organize the athletic events and … sports days’… umpiring barefoot soccer games. ‘…he always inspired enthusiasm; strong as he was in his conviction about Sunday not being a day for sports, he even agreed to referee the games of some children whose parents let them play on Sundays, when he found them fighting over the game. To us young people in camp, he was known as Uncle Eric. To us he stood out as kind and friendly, with his ever-present smile and gentle, Christ-like manner… he loved children and gave a lot of time to…us… because we were the youngest without our parents. Though… ‘he missed his family very much… he wasn’t looking for pity. To accept with quiet serenity the will of God was the hallmark of his life…’

‘One wintry day in February, I was with our little group… when we saw Eric walking under the trees…. As usual he was smiling. As he talked with us, we knew nothing of the pain he was hiding, and he knew nothing of the brain tumour that was to take his life that evening, February 21st, 1945, when he, one of the world’s greatest athletes would reach the tape in his final race. He was 43 years old… in his last hour he was writing the words of his favourite hymn, and those words brought solace to his soul as they had before when he gave them to the mother whose son had been electrocuted: “Be still, my soul, the Lord is on thy side; bear patiently the cross of grief or pain; leave to thy God to order and provide; in every change he faithful will remain. Be still, my soul, thy best, they heavenly Friend through thorny ways leads to a joyful end”. The evening snow was falling gently as Eric Liddell died, a soul serene amidst the sorrows and sufferings of the war that was to end six months later. His last words were, “It is complete surrender.”’

‘Beryl Welch, aged fourteen, and a daughter of one of our Chefoo teachers, wrote in her diary of February 22, 1945: “Dear old Uncle Eric died last night. It was so sudden. He wrote a letter to his wife just that day. Everyone was greatly impressed. I feel sorry for her. Most people thought he was the best man in camp. What a loss! It snowed today. There was no coal.”

One man who wasn’t a Christian said, “Yesterday Jesus Christ lived among us; today he is no longer with us.”’ He wasn’t altogether wrong, for Eric Liddell could say with Paul: “For me to live is Christ, and to die is gain.”

Taken from the notes of a fraternal paper by Paul E. Brown

Part 3 is here.