The founder of Christian reconstructionism was Dr Rousas J. Rushdoony, an American Presbyterian minister and scholar, whose obituary we carry in this issue.

In 1965 he formed an organisation called the Chalcedon Foundation and in 1973 he published The Institutes of Biblical Law. Another well-known reconstructionist is Dr Greg Bahnsen who wrote Theonomy in Christian ethics, a 650-page work that is widely distributed. A third advocate is Dr Gary North who has written more than 25 books promoting reconstructionism in its various forms.

Kingdom theology

Terms like ‘Dominion theology’ or ‘Kingdom theology’ are familiar words associated with reconstructionists. They believe it is the duty of Christians to bring about a restored paradise on earth before the coming of Christ.

It will be an earthly kingdom patterned on the societal framework given to ancient Israel prior to the monarchy. Every nation must adopt the Mosaic laws if the world is going to see peace and prosperity.

The principal goal of reconstructionism is thus the political and religious dominion of the world through the implementation of the moral, social, judicial and economic laws of the Old Testament.

Some Charismatics have embraced reconstructionism and are looking forward to a victorious scenario of mass conversions, and political supremacy in the near future.

Postmillennial

All reconstructionists hold to a postmillennial view of eschatology. They believe that human society will improve and that the kingdom of God will grow so mighty in size, strength and influence, that the world will become totally Christianised before the return of Christ.

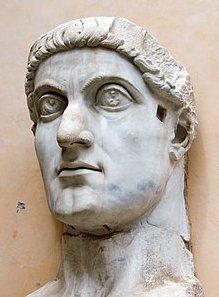

Many of them draw historical parallels with the rule of the Roman Emperor Constantine, who made Christianity an official religion in the Roman Empire during his reign (A.D. 313–337).

Others cite Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658) who ruled as ‘The Lord Protector’ during the Puritan era in England in the 1650s, and Abraham Kuyper (1837–1910), a Dutch pastor and theologian, who became the Prime Minister of Holland (1901–1905).

However, none of these examples, when taken in their respective historical contexts, give support to the ideas of theonomy. Constantine’s support for Christianity signalled a decline, rather than a rise, in biblical doctrine and practice. Although he was a Bible-believer, Cromwell did not impose Bible-based laws but, rather, encouraged religious tolerance.

Whose work?

What is wrong with reconstructionism? It is wrong in that it fails to realise that the world lies under the judgement of God. The work of reconstruction is not the church’s, but Christ’s when he returns.

In this present world-order, God has ordained that society should be ruled and governed by civil authorities and magistrates, not by ecclesiastical or spiritual leaders. Christians are required to submit to the secular ‘powers that be’ in their administration of justice, for they are ‘ordained by God’ (Romans 13:1- 17). Jesus, for example, paid the tax required by the secular government (Matthew 17:24 – 27).

Paul did not launch a crusade against the injustices of slavery in the Roman Empire. What he did do was to exhort Christian slaves ‘to be obedient to their masters, and to please them well in all things, not answering again’ (Titus 2:9).

Peter likewise exhorted: ‘Submit yourselves to every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake: whether it be to the king as supreme; or unto governors, as unto them that are sent by him for the punishment of evildoers, and for the praise of them that do well’ (1 Peter 2:13-14).

Christian citizens

But should Christians not seek to influence politicians in their law-making? Yes, of course. As citizens they have both the right and responsibility to influence society for good. Legislation concerning research on embryos and the age of consent are examples where Christians have properly made their voices heard.

But theonomy goes much further. It teaches that Christians should take control of the legislative process and use their political power to impose the Mosaic system of law upon society.

By contrast, Paul defines the legitimate boundaries of Christian political ambition when he urges prayer ‘for kings and all who are in authority, that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life in all godliness and reverence. For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Saviour’ (1 Timothy 2:1-3).

Novel approach

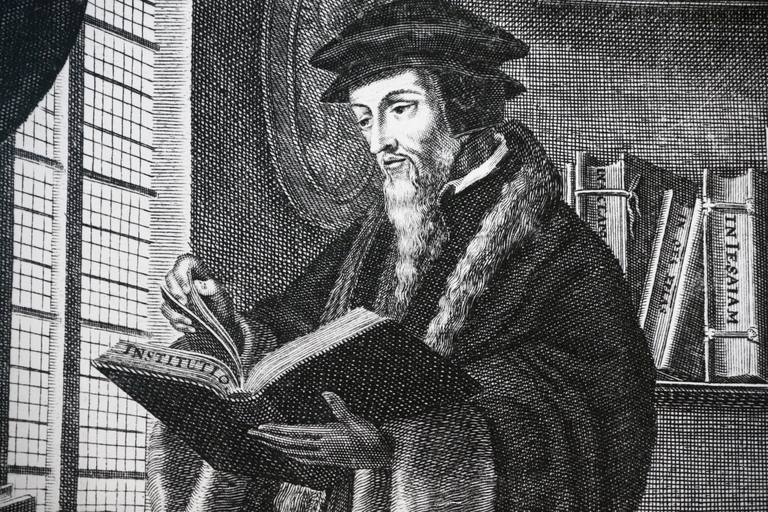

Is theonomy theologically sound, biblically defensible, and consistent with Calvinism? Robert Godfrey has this answer: ‘The appeal of theonomy, like that of many contemporary Christian movements, is its simplicity and apparently biblical character. The great complexities and frustrations of the secular, modern world lead many to look for easy solutions.

‘But in a fallen world, solutions to great political problems are not always easy. The approach of theonomy is a novel one in the Reformed community and uses the Scripture in a way that is alien to Reformed Christianity’.

Rushdoony called Calvin’s view of the civil law ‘heretical nonsense’. Calvin called a form of theocratic thinking remarkably like theonomy ‘false and foolish’. When it comes to law and civil government, Calvin and theonomy do not have much in common (Theonomy: A Reformed critique, edited by William Barker and Robert Godfrey, Zondervan 1990, p.312).

Extreme

While we decry the antinomianism that is so rampant today, we do not want to swing to the other extreme of imposing upon a nation the demands of the Mosaic penal code.

The social-political laws of the Mosaic economy were abrogated with the advent of Christ, and are neither appropriate nor necessary today. Israel was God’s chosen nation, and God had stringent regulations and rules for them. But these were given for a specified purpose and period.

However, God’s moral laws are perennial and are to be obeyed, not in letter only, but much more in spirit. Paul declares himself to be a minister ‘of the new covenant, not of the letter but of the Spirit; for the letter kills but the Spirit gives life’ (2 Corinthians 3:6).

The New Testament nowhere suggests Christian dominion over the present world system in the way proposed by theonomists. As Dr Carl McIntire has said, our duty is not to mass-convert the world, but rather to accelerate the Great Commission to the ends of the earth, for a witness to all nations before Jesus returns.

Mission

The Lord’s plan of salvation is not the new theonomy, but the old theology, namely, a worldwide mission to as many as will repent and believe the gospel.

According to Dr Howard Carlson, mission is on the decline; the average age of missionaries in the West today is 60.

The Bible-Presbyterian churches are a young movement with plenty of young people, as also are other Reformed causes today. The greatest contribution we can make to the work of Christ in this present age is to take up the cross and follow the Lord wherever he leads.

Our objective must be, not to exert political control over human society, but to save souls and plant churches.

Let us take our stand with Isaiah, who declared: ‘I heard the voice of the Lord, saying, Whom shall I send, and who will go for us? Then said I, Here am I; send me’ (Isaiah 6:8).

The author is pastor of Maranatha Bible-Presbyterian Church, Singapore. This (edited) article is reprinted from the Maranatha Weekly of 9 July 1995.