Nine centuries of decline

Pope Gregory died in A.D. 604. The next 900 years were to be an age of moral and spiritual decline. It is true that Christianity continued to expand. The Roman Catholic Church extended its influence eastwards into Moravia and Bulgaria during the ninth century, into Poland and Russia during the tenth, and into Hungary during the eleventh. It expanded northwards into Denmark and Norway during the eleventh century, into Finland and Sweden during the twelfth, and into Lithuania during the fourteenth.

However, the Christianity brought to these areas was a far cry from the faith taught in the New Testament. From the seventh century onwards, Christianity became increasingly superstitious. This can be seen in several ways.

Cure for toothache?

In the first place, people came to view the sacraments as magical rites. They thought that baptism actually washed away a baby’s sins. As regards communion, the doctrine of transubstantiation taught that the bread and wine really changed into Christ’s body and blood. This did not become official church doctrine until 1080, but most people believed it long before then.

Then there was the veneration of the ‘saints’ and, especially, Mary. People believed the ‘saints’ were able to help and intercede for them if called upon in times of need. Some saints had specialised work.

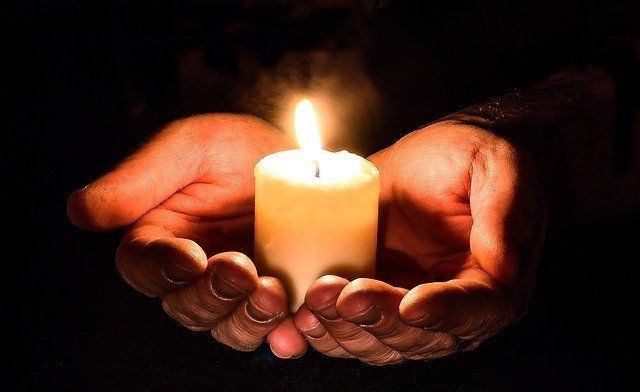

St Erasmus was (reputedly) good at praying for God to heal people with stomach ache. Lighting a candle in front of a picture of St Eligius would make your horses thrive. If you called on St Christopher before starting a journey, he would protect you as you travelled. St Apollonia was believed to be particularly expert at answering prayer for the cure of toothache.

As for Mary, she would plead with Jesus on behalf of any sinner. People believed that she was full of compassion and could negotiate forgiveness for them by interceding with her more reluctant Son. This was not only unbiblical but a travesty of the truth about our Lord.

Relics and indulgences

There was also a great emphasis on ‘relics’. These were supposed to be fragments of holy objects (and even of people!). To possess a ‘relic’ was a guarantee of safety in life. It was the medieval equivalent of buying insurance.

So merchants would carry splinters from the cross to protect them from thieves. Soldiers would carry a tooth or hair of a saint, to help them win in battle. Kings would obtain a few drops of Jesus’ blood, or a nail from the crucifixion, to increase the glory of their own reign. Of course, all these ‘relics’ were spurious, but it was a very good way for the church to make money!

There was another money-making racket: the sale of indulgences. An indulgence was a kind of certificate. People generally believed (because this is what they were taught) that they would have to go to purgatory before finally reaching heaven.

In purgatory they would endure torments for a certain time to make them pure enough to be admitted to heaven. If they bought an indulgence, they were told, their time in purgatory would be reduced.

The result was that people felt that they could sin without concern: they just had to buy an indulgence to escape the consequences. What is more, the work of Christ as the fully sufficient basis for the forgiveness of sin was completely obscured.

Widespread ignorance

In other words, the church was using superstition to exploit people. As a result, the clergy (especially the pope and the cardinals who were at the top of the hierarchy) lived in the lap of luxury.

Their lavish lifestyle was associated with two things. The first was a preoccupation with idleness and pleasure. Many clergymen were gluttons and drunkards who spent most of their time engaged in sport (which in those days meant hunting).

Secondly, the clergy often lived scandalous lives of sexual immorality. Some medieval popes lived openly and unashamedly with mistresses, and even allowed their illegitimate children to live off church funds. The lower ranks of the clergy were equally immoral, despite the fact that every clergyman had taken a vow of celibacy.

There is little wonder that ignorance of Christian truth was widespread. By A.D. 800 most clergymen were unable to recite the Lord’s Prayer. It is hardly surprising, then, that the population in general was unaware of what true Christianity really was.

Buy a bishopric

During this 900-year period the church was becoming less and less distinguishable from the State. Bishops became politicians, and secular powers came to dominate the church.

For example, Charlemagne, who was King of France from 767 to 800, and then Roman Emperor until 814, used to preside at Church Councils. The church was a battleground of warring factions. Rulers would appoint their favourites as bishops as a reward for services to the State. Sometimes they appointed men who were not even ministers.

Two particular evils grew up. One was simony. This meant that office in the church was for sale: you could buy a bishopric if you fancied the job. The practice derived its name from Simon Magus, who offered the Apostles money for the gift of the Holy Spirit (Acts 8:19).

The other evil was nepotism. This meant appointing one’s own relatives to high office. For example, Sixtus, who was pope from 1471-84, made six of his own nephews cardinals. It’s just as well that his name wasn’t Eleventus!

Power-mad

In such a climate, men completely lost sight of the spiritual nature of Christianity. The church had become power-mad, to the extent that the torture and execution of dissidents was a constant feature of medieval life.

A classic example was the treatment of the Waldensians. Their origins are uncertain. The name derives from Peter Waldo, although the group predated him. Waldo was a successful merchant banker from Lyons.

He was aroused to his need of salvation by the sudden death of a friend in the 1150s. In 1160 he employed a secretary to translate the Bible from Latin into his own language. Once he could read the Bible for himself, he was challenged by Matthew 19:21, where Jesus says to the rich young ruler, ‘Sell what you have and give to the poor’.

After meditating on these words for some years, Waldo sold his property in 1173, distributed the proceeds to the poor, and devoted himself to the study of the Bible.

In 1180 he became a travelling preacher and others joined him. They were nicknamed ‘The Poor Men of Lyons’. They regarded the renunciation of property as a protest against the wealth and laxness of the Roman Church.

The very next year the Bishop of Lyons tried to prohibit their activities, and in 1184 the pope excommunicated them and they fled from Lyons. Later the Waldensians were subjected to the Inquisition.

Inquisition

The Inquisition was founded in 1210 and was made a permanent institution in 1229 by the Council of Toulouse. It was an elaborate court with dozens of officials. It was given power to examine the actions and the intentions of people. It operated in a way which can hardly be described as exemplary justice.

The procedure was as follows. The Inquisitor arrives in a town. He requests the names of any suspected of ‘heresy’. He informs the people of a period of grace, during which suspects may confess and recant.

After that period has expired, suspects who have not come forward are brought to trial. The trial takes place in private. Two witnesses against a person are sufficient, and the witnesses may remain anonymous.

The charges are vague, and it is impossible to find a defence lawyer, because the legal profession has quickly learnt that to defend a suspect is to become the Inquisition’s next victim.

Torture is applied to force the suspect to recant. If he is found guilty he may be disqualified from civil office, sent to prison or, in the worst cases, burned at the stake.

As far as the Waldensians were concerned, their ‘heresies’ included possession of the Bible in a language other than Latin; preaching by men unauthorised by the Roman Church; and rejection of the view that priests are mediators for laypeople.

The Inquisitors did sometimes admit that it was difficult to pin ‘heresy’ on the Waldensians, for they held to an orthodox creed and lived lives of outstanding piety. Their only crime was ‘blasphemy’ against the Roman Church and clergy.

We see here what ‘heresy’ really meant. The issue was one of power. The Roman Church had become an omnipotent institution at the centre of a totalitarian empire. Politically, it was at the forefront of medieval life. But spiritually it had declined to rock-bottom. It no longer possessed the message of life and salvation.