Could this be the death of Darwinism?

On Thursday 6 September 2012, the Guardian newspaper carried a dramatic headline on its front page, announcing that ‘Breakthrough study overturns theory of “junk” DNA’.

|

| http://genome.ucsc.edu/ENCODE/aboutScaleup.html |

The story was carried by many newspapers and news bulletins and soon the blogosphere was buzzing with a mixture of excitement and consternation.

Many people, understandably, could not see what all the fuss was about, but for those who had been following the ‘junk DNA’ story this was a ‘make or break’ moment.

The cause of all the hoo-ha was an announcement made jointly by more than 400 scientists working in several different laboratories in different parts of the world.

They had reached the end of a major project, entitled ENCODE, initiated in 2003 and working fully since 2007. Their findings are summed up in 30 different academic papers published simultaneously in four different scientific journals, with the leading journal Nature carrying the main paper.

It is not often that such a major announcement is made by so many scientists working together; and these discoveries are regarded as comparable to the announcement regarding the Higgs Boson particle in their level of importance.

No junk

The central finding of the ENCODE project is that, effectively, all of our DNA — the genetic material that we carry in our cells — has a purposeful function.

The researchers have established this with certainty for 80 per cent of the genome and fully expect that, with more investigation, the remaining 20 per cent will be seen to be functioning as well.

To those of us who are used to thinking of the human body as fearfully and wonderfully designed by a Creator, this does not sound very surprising. Surely that was what they were expecting to find?

Regrettably, it was not. Until very recently, 98 per cent (yes, 98 per cent!) of the DNA was regarded as ‘junk’; it was deemed to be useless DNA left over by millions of years of random evolutionary changes.

The imagined existence of ‘junk DNA’ has, for the past 40 years, been seen by many evolutionists as one of their strongest arguments against the view that living things are designed and created by God.

By the 1960s, it had been established that DNA was the biochemical substance which caused our genetic make-up and that it carried a code — the genetic code — which enabled the cells in our bodies to make the different proteins that we need in order to exist.

The idea was that each protein had its own gene and that was all there was to it. However, by the 1970s it was realised that not all of the genes coded for proteins. At that point, it was decided that the rest of the DNA, the non-protein-coding genes, were simply ‘junk’, rubbish that had accumulated during the process of evolution.

Eventually it was established that only about 2 per cent of the DNA coded for proteins. To the great majority of Darwinian evolutionists, 98 per cent was therefore junk.

There were always a few dissenting voices who argued that one day the functions of the remaining 98 per cent would be discovered. For decades, creationists have been making that point at every opportunity.

In more recent years, they have been joined in this by intelligent design advocates, culminating with the publication in 2011 of the book, The myth of junk DNA, by Jonathan Wells.

Growing doubts

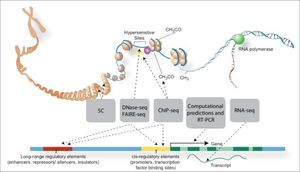

By this time, early results from the ENCODE project were beginning to trickle out and it was becoming clear that there was evidence of function and purpose for at least some of the non-protein-coding DNA. Nevertheless, until 5 September 2012, it was still widely claimed that the majority of the DNA was junk.

Three important issues have been radically affected by the new discoveries. First, it can no longer be claimed that creationists and intelligent design advocates cannot make predictions and, therefore, cannot be regarded as doing ‘science’.

For decades, they have been predicting that if purpose was looked for in the ‘junk’ DNA, it would be found. This did not happen until the Human Genome Project demonstrated, in 2003, that there were only 20,000 protein-coding genes in the human genome, far fewer than had been expected.

At this point it was fully realised that it was necessary to look elsewhere to account for the complexity of human development and the ENCODE project began its work.

The second point follows from the first. It concerns the power of a scientist’s world view to affect how the evidence is being perceived. Creationists expected the DNA to be complex, to be performing vital functions that were not apparent at a first glance.

They urged the evolutionary scientists to think in terms of complex information and to look for it. Darwinian evolution requires the genetic apparatus to be simple. The more complex a structure is, the harder it is to account for how it will have arisen in the first place and the more likely it is that a random change in it will be harmful.

The Darwinian scientists who promoted the ‘junk DNA’ myth looked at the genome and thought they saw damaged, meaningless material. They were wearing the wrong spectacles. Once forced to look again at the ‘98 per cent’, this time expecting to find some function, it soon became apparent that it is there.

Compelling evidence

The third point is the most important of all. The ENCODE project has uncovered an unimaginable level of complexity, which is engendering a greater humility in at least some of those who work in genetics.

The Guardian article on 6 September carried an interview with Dr Ewan Birney, one of the leading ENCODE scientists. The article quotes him as saying that the decade since the publication of the first draft of the human genome has shown that genetics is more complicated than anyone could have predicted.

They then quote him directly: ‘We felt that maybe life was easier beforehand and more comfortable because we were just more ignorant. The major thing that’s happening is that we are losing some of our ignorance, and indeed it’s very complicated.

‘You’ve got to remember that these genomes make one of the most complicated things we know: ourselves. The idea that the [human genome] would be easy to understand is hubris. I still think that we are at the start of the journey, the warm-up, the first couple of miles of this marathon’.

The word ‘hubris’ is defined as ‘excessive pride or self-confidence’. This new generation of geneticists aspires to a greater humility. On the Nature web site can be found an open-access area dedicated to ENCODE, where they spell out what has been discovered and how they see the future of their project.

They are suggesting that it will be the end of this century before the human genome is fully understood, if indeed it ever can be, such is the complexity of what they have found.

Death blow

It is claimed that Darwinian evolution is supported by two main lines of evidence: the fossil evidence and genetic evidence. Of the two, the genetic evidence has been regarded by many as the more important.

In my view, the genetic evidence has just been demolished at a stroke, because it is now admitted that it is so little understood and what is now known is so difficult to reconcile with Darwinism.

No doubt, it will be a long time before the latter is fully admitted and in the meantime, behind the scenes, there will be frantic efforts to produce non-Darwinian theories of evolution. Nevertheless, as I see it, we are now witnessing the death of Darwinism.

Sylvia Baker PhD, BSc, MSc